“As a result of study of damage sustained by various British carriers prior to our entry into the war, two important departures from traditional U.S. Navy carrier design were incorporated in the CVB Class, then still under development. HMS ILLUSTRIOUS in an action off Malta on 1 January 1941 was hit by several bombs, three of which detonated in the hangar space. Large fires swept fore and aft among parked planes thereby demonstrating the desirability of attempting to confine the limits of such explosions and fires by structural sectionalization of the hangar space... The damage experiences of several British carriers, which unlike our own were fitted with armored flight decks, demonstrated the effectiveness of such armor in shielding hangar spaces from GP bombs and vital spaces below the hangar deck from SAP bombs. Accordingly, the CVB Class was designed with an armored flight deck consisting of 3-1/2-inch STS from frames 46 to 175 with a hangar deck consisting of two courses of 40-pound STS between frames 36 and 192. Although none of the CVB Class carriers were completed in time to take part in war operations, the effectiveness of armored flight decks against Kamikaze attacks was demonstrated by various carriers attached to the British Pacific Fleet...

”

DEBUNKING SLADE & WORTH'S

ARMOURED CARRIER ESSAYS:

The essays of Slade and Worth on the NavWeaps website which compare Britain's armoured carriers to the performance of the United States' carriers have become the generally accepted "internet authority" on the subject. But scratching the surface of their work reveals the essays to be riddled with factual error, a lack of knowledge relating to Mediterranean and Atlantic operations, as well as minimal understanding of the circumstances of Task Force 57's operations off Sakishima Gunto.

The magnitude of such factual errors render their conclusions suspect.

The following rebuttals aim to set the record straight.

Draw your own informed conclusions.

OVERVIEW

“… a Kamikaze hitting a steel deck crumpled up like a scrambled egg and did relatively little damage, whilst one crashing the wooden flight deck of an American carrier usually penetrated to the hangar deck and raised hell below.

”

KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER

1) HMS Ark Royal (91) was designed to operate in the open waters of the Pacific, as Japan was seen as the greatest threat to the Empire in the early 1930s. Therefore it has more similarity in concept to the US carriers than the later Illustrious type carriers.

2) HMS Illustrious was designed with a greater emphasis on operations in the closed waters of the Mediterranean and North Sea as war with Italy and Germany was seen as the greatest threat to the Empire in the late 1930s.

3) The Illustrious group were designed with an armoured hangar (incorporating 62 per cent of the flight deck). Not an armoured flight deck. This was intended to protect the hangar from 6in gunfire and 550lb bombs, separate the volatile material it contained from damage sustained externally, as well as to prevent damage to the hangar from extending to the remainder of the ship.

4) The first four ships of the Illustrious class were designed under treaty limitations. The final two (Implacable and Indefatigable) were laid down under treaty limits, but reworked somewhat after these were abandoned.

These treaties also applied to the design and construction of the Yorktown class. The later Essex class was released from these restrictions. So the most valid point of comparison is between the Illustrious and Yorktown types.

5) The Illustrious class and sub-classes fought in the Arctic, North Atlantic, North Sea, Mediterranean, Indian Ocean and Pacific. The only available direct comparison point with the US carriers is the 1945 Pacific campaign.

6) All post-war carrier designs had armoured flight decks (not hangars). Enclosed hangars, however, soon made a comeback with Cold War concerns about nuclear fallout.

Grave of a Dozen Schemes:

British Naval Planning and the War Against Japan, 1943-1945

By H. P. Willmott

Book Forward: "It would be pleasing to record that this book first saw the light of day as a result of a conviction that the story of the British contribution to the war against Japan in 1944-45, and specifically the story of the British Pacific Fleet, deserved an account that did both justice.

Unfortunately this author cannot honestly make such a claim.

This book took shape as a result of the realisation that a doctorate, and with it admission to the most mysterious Masonic order in the Western world, would be required if the author was to work in the United States".

Rethinking History Blog comment: In other words, I tailored my stuff to what people in university circles wanted to hear to be acceptable to the powers that be in (United States) academia…

COMPARISON OF BOMB WEIGHTS.

The bombs that hit the armoured carriers in the Mediterranean were 550lb and (according to US and British analysis - as well as X Fliegerkorp’s and Italian reports) 2200lb.These were often dropped at optimal release heights by trained pilots (X Fliegerkorps) to gain maximum effective penetrative velocities. However, maneuvering warships would often force even experienced dive-bomber pilots to release lower in order to increase their chances of a hit in exchange for poorer penetration potential.

It's also important to note that armoured carriers had the effect of forcing opposing bombers to heft heavier armour-penetrating type bombs which, in turn, reduced their strike radius.

The bombs used against the US and Britain in the Pacific tended to be 550lb (250kg) weapons (the No.25 Model 2, 253 kg (557 lb) featured most prominently, especially at Midway). And the most commonly available armour-piercing bomb (Type 99 No.80 Mk 5) was a modified naval AP shell. By 1945, these bombs were usually dropped at very low altitudes or left strapped on kamikaze aircraft, drastically reducing their penetrating properties.

No US or British fleet carrier was sunk by bombs alone. Even the Japanese carriers lost at Midway appear to have all been scuttled by torpedo. But bombs did have the potential to disable a ship and make it vulnerable to follow-up attack.

DOCTRINE DIFFERENCES

Yes, the armoured carriers were built in large part due to the RN's and RAF's pre-war lack of faith in naval-based fighter aircraft and a fear of prowling cruisers.

It was the same challenge that saw the late 1930s development of the Dido-class dual-purpose cruisers, the rebuild of some World War One era cruisers into anti-aircraft ships and the rebuild of the battlecruiser Renown and dreadnoughts Queen Elizabeth and Valiant as carrier escorts with strong anti-aircraft capabilities (ten twin 4.5in HA mounts each).

The Illustrious class was built under dramatically different circumstances to the open expanses of the Pacific. Naturally, one would expect European conditions not to be prominent in US design considerations.

The Pacific needed extended operations outside of the “convenient” range of bases such as the Home Islands, Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria etc. Therefore, larger carriers with greater airgroups (with spares) and endurance were a given in order to sustain operations.

Britain also recognised this: Ark Royal, built at a time when Japan was believed the most likely enemy, was designed with these factors in mind.

Arching over this, however, was the outcome of wargames by both the US and UK in the 20s and 30s. These demonstrated the inherent vulnerability of aircraft carriers to air attack. As such, the carrier that got in the first strike almost always won.

The US solution to this dilemma was to consider building a large fleet of small carriers (though the small ships component was never implemented). At least some decks would survive the first strike, they thought. This eventually evolved into the 'dispersed carriers' doctrine where even carriers operating together would be positioned separately from each other and the main fleet bodywith their own escorts in order to reduce chances of all of them being discovered. This doctrine persisted until well into 1943.

The British solution, along with a shift of the axis of their primary threat from Japan to Italy and Germany, was to increase the survivability of their fleet carriers through armour and other "passive" defence devices such as their avgas fuel containment systems, hangar sprayers, fire curtains and deep magazines. A smaller air-group was considered an acceptable trade-off as the naval fighters of the time appeared to be on the brink of being useless. Ironically, British doctrine was evolving towards multi-carrier task groups - though war circumstances generally prevented this from happening.

BUILT TO HANDLE WEATHER

The North Atlantic was not a force Japan or the United States planned to contend with. It was, however, front-and-centre to RN operational requirements.

Hurricanes, heavy seas, frequent rain squalls - along with ice from spray and snow - presented significant challenges to ship strength and stability. Not least of all carriers.

It was the main reason for Britain's tendency to keep aircraft stowed below, and not on the flight deck. It was a reason behind the enclosed hangar and having the strength deck at the flight deck - the entire ship's side was watertight (as well as gas tight and light tight). It also was the thinking behind the RN carriers' prominent - but efficient - enclosed 'hurricane bow'.

By the August 1945, when the combined units of Task Force 58 were battered by a typhoon on the 26th, the RN was using extensive deck parks in the Pacific. But, where USS Wasp had her forward flight deck collapse and USS Randolph also suffered damage, HMS Indefatigable was justifiably cheeky in its response to Admiral Halsy's query about her status - "What typhoon?"

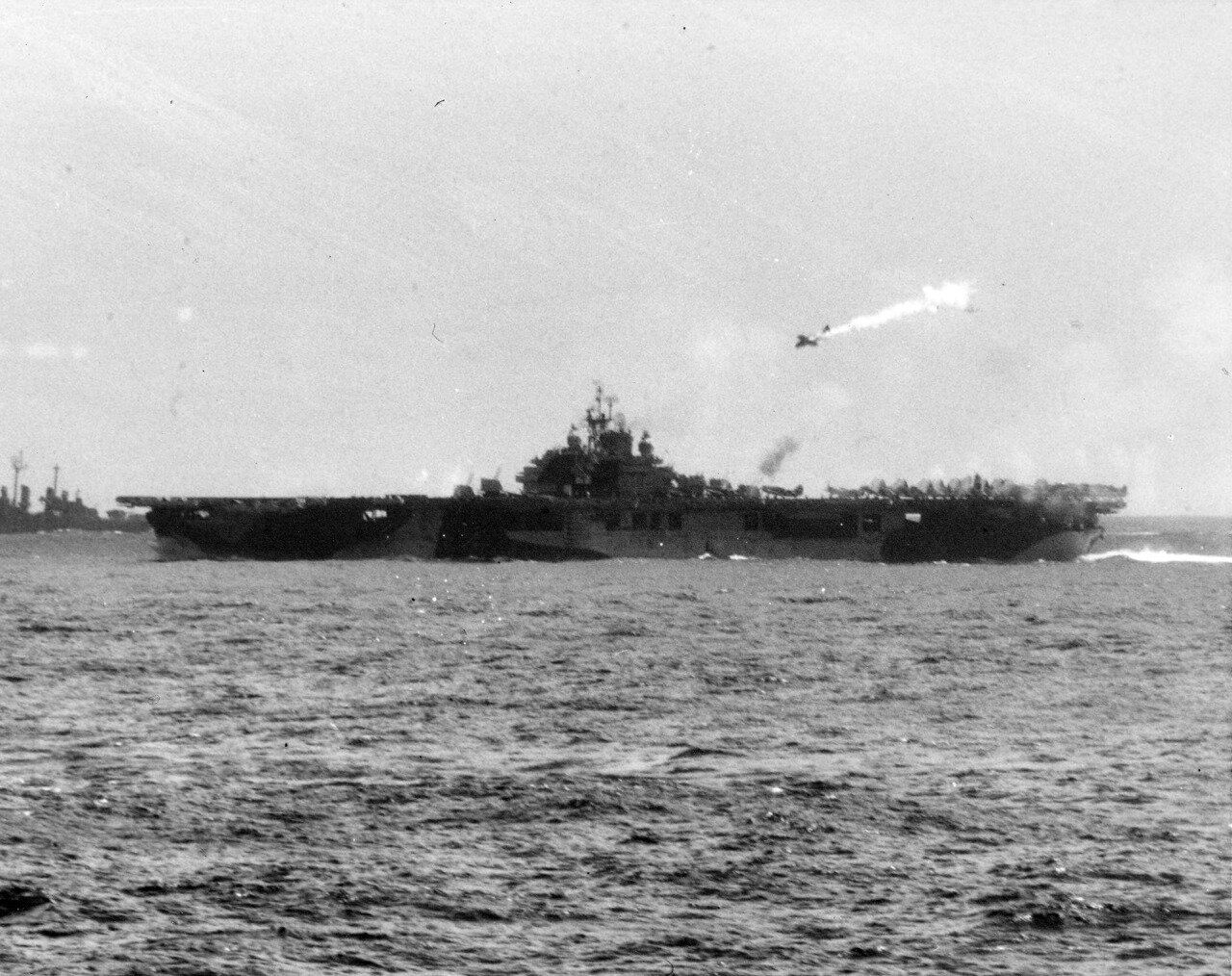

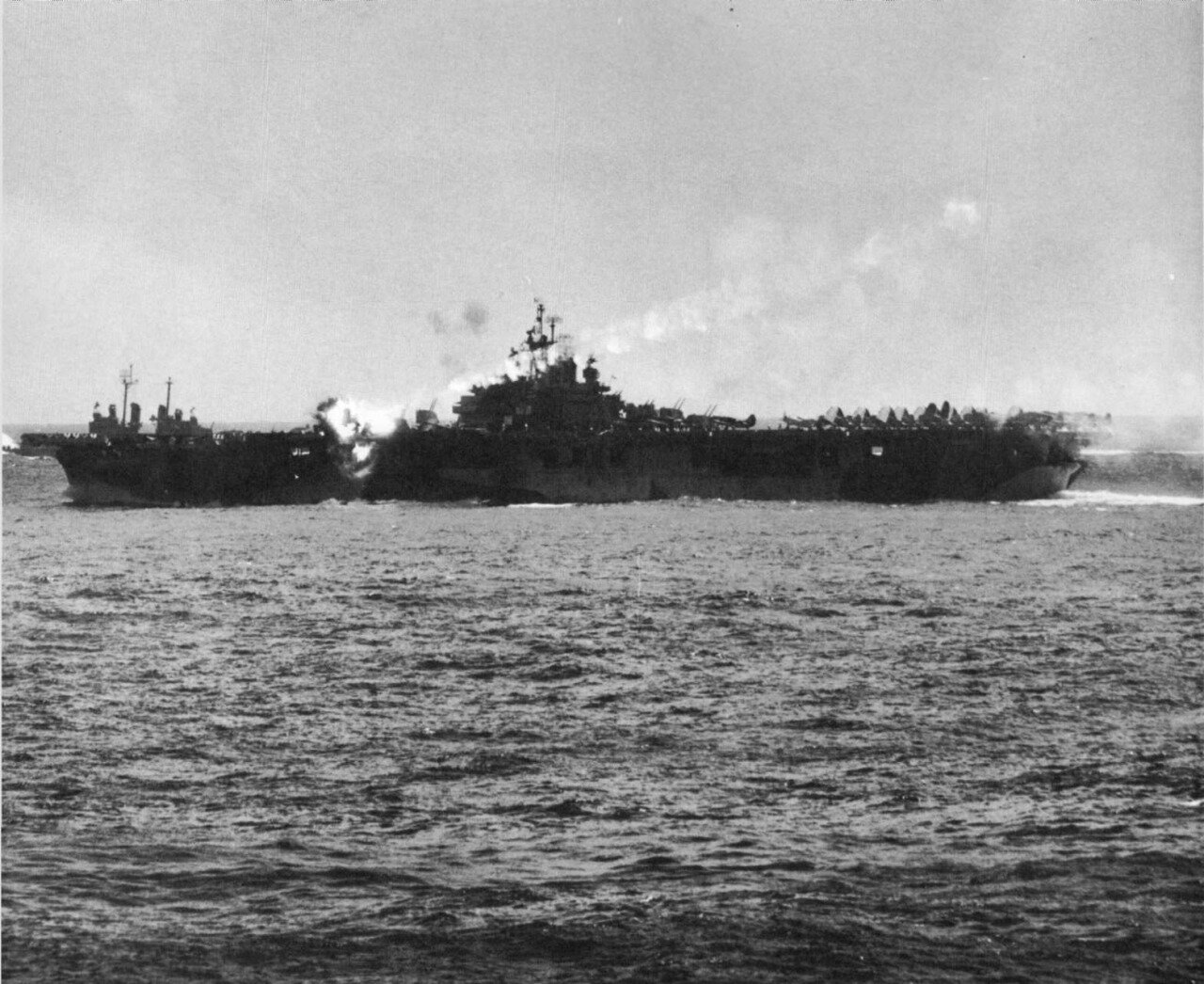

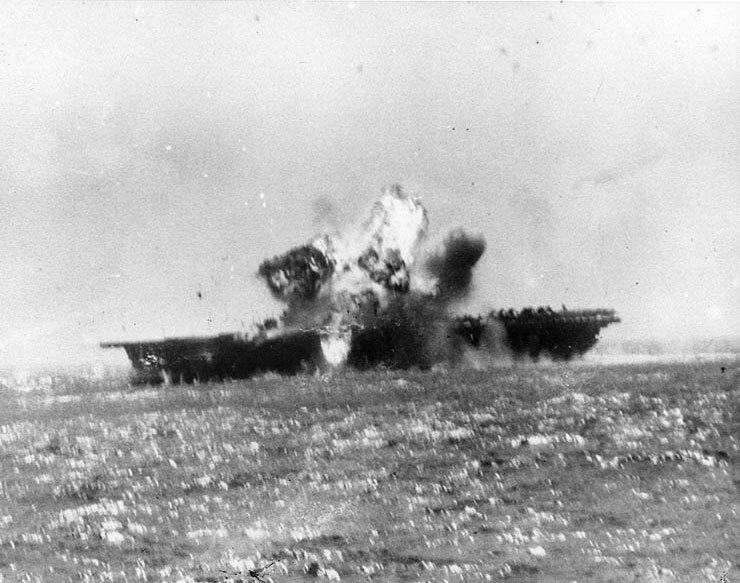

HMS FORMIDABLE vanishes behind a fireball moments after a kamikaze detonated on her flight deck in May, 1945.

APPLES WITH APPLES

The Essex is a 1940s ship built after the abandonment of treaties and amid the first practical lessons of war from Europe. The Illustrious is a 1936 design and built under treaty restrictions. It is like comparing the Fulmar to the Hellcat – one of which belongs to a generation which learned and built upon the generation preceding it.

The Illustrious class (1937) falls between the USS Yorktown Class (1934) and the Essex class (1941). As the Yorktowns were also built under treaty restrictions, they are the closest reliable comparison point.

The Essex class, designed and built after the outbreak of war in Europe, is much more contemporary to the Audacious design (though Britain simply could not build big ships as fast as the US).

The first “true” carrier war began in September 1939: It was the Royal Navy that was fighting it (and making it up as it went along) as nations such as the US and Japan looked on - and learned.

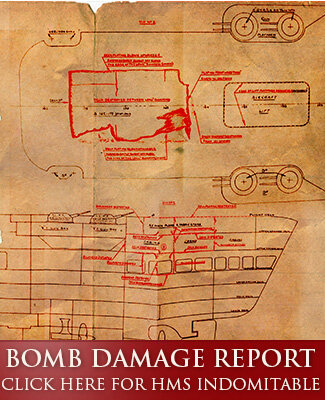

Click on the above image for an expanded view. This is a Norfolk Navy Yard comparison drawing of the side armour arrangements of the treaty-era HMS Illustrious (1940) and a post-treaty Essex (1943). Picture courtesy 'Researcher at Large'

“The Americans with all their great qualities are so optimistic about their deeds and so generous in their claims that it is sometimes difficult for us here even to remember that we have done certainly as much and probably more air fighting at sea than they have under incomparably more difficult conditions.

Even so, our carriers are still afloat and although generally engaged with enemy shore based aircraft having ridiculously old and inadequate aircraft themselves have in most cases beaten off the enemy with heavy losses.

We are striving with all our power to get better aircraft and to improve our carriers. You will see the results of this effort before very long.

Frankly I am distressed by your letter. If your air advisers really think so poorly of their confreres over here it is deplorable and I think on the whole that our judgement is as good as theirs.

”

OUTCOMES?

The carrier designs at the end of the war represented a convergence of ideas.

The performance of the armoured flight deck against the kamikaze saw it become a feature of all future designs - US and British. This necessitated the flight deck becoming the strength deck.

However, the weight cost of the armour enclosing a hangar was judged to be too great. The 'box' concept was gradually downplayed, first with Indomitable and then with the Implacables, until essentially abandoned after the Audacious class.

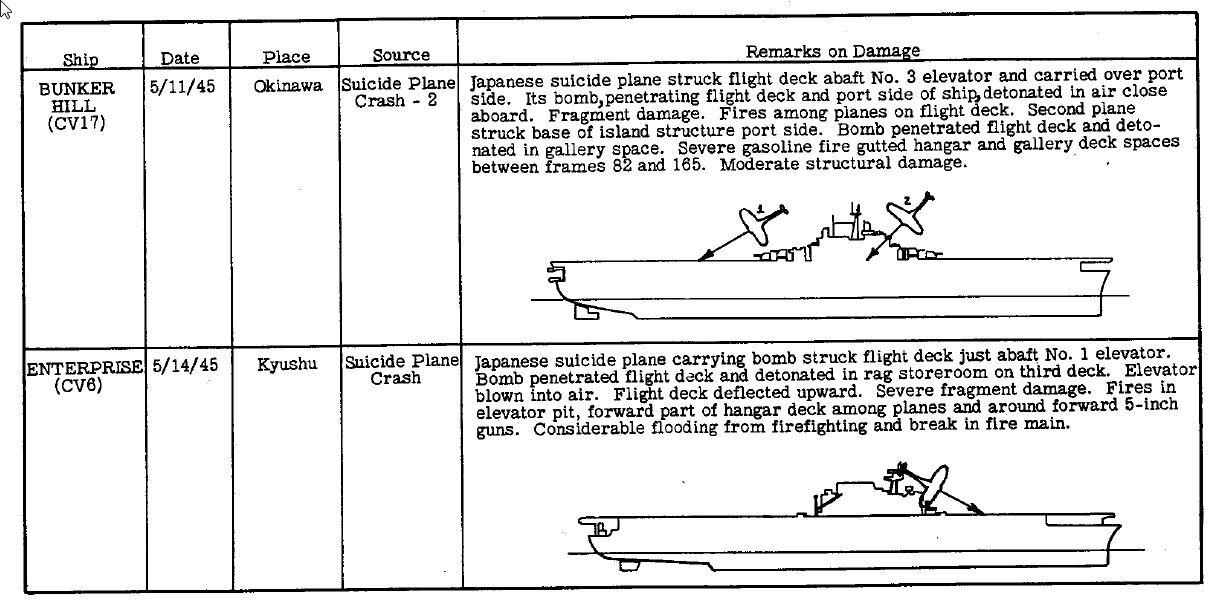

But the tragic death tolls aboard USS Bunker Hill and USS Franklin - when compared to that of HMS Illustrious - instilled a new and deep respect for the volatility of a carrier's own aircraft and weapons.

“Of course living among Americans who belittle our aircraft and our carriers and who are very conscious of their own successes, it is difficult for anyone to keep a balance. I found this very much the case when I was living in the [U.S.S.] SARATOGA. Only today has a report on our carriers by a U.S. Air officer been shown to me. It is a travesty of judgement and could only have been written by one so blinded by the Coral Sea and Midway battles that he was unable to see the Malta convoys in which a scale of attack, happily still unknown to our cousins, was met and defeated.

Sorry to have taken up so much of your time but the facts you quote are biased, and we should be seeing eye to eye.”

'No Place to Land': Corsairs wearing the 'Q' mark of HMS ILLUSTRIOUS fly over HMS FORMIDABLE as she burns after a kamikaze struck her armoured flight deck abreast the island. (This isn't possible unless these were 'spares' from Illustrious waiting to be repainted as she had left the BPF when Formidable joined). Painting by Michael Turner

““ The US Navy learned its lesson the hard way during World War II when all its carriers had only armored hangar decks. All attack carriers built since the Midway class have had armored flight decks.”

”

Armor Protection on American and British Carriers

©2000 Stuart Slade

This is a VERY complex design issue that defies easy answers. The question is not so much whether armor is useful (both US and British designs had very roughly comparable armor protection in terms of weight) but where does the designer put it.

The complexity is a given, and – as such – should remain foremost in the mind throughout the WHOLE argument.

Not acknowledged above is that there is also the question of what the armour and hangar was designed to achieve given the circumstances under which the ship was expected to operate.

British design practice with the Illustrious and Implacable classes was to armor the flight deck, making the flight deck the strength deck. The plusses here are that if the armor holds, bombs can be kept out of the ship completely. The negatives are that the size of lifts is restricted, stability problems are hellish and the airgroup capacity is comparatively small.

Given the aforementioned complexity, a few things need to be clarified:

- The “armoured flight deck” was, in fact, not an armoured flight deck. Illustrious had an armoured hangar, which incorporated roughly 62pc of the flight deck.

- The flight deck around the smaller lifts were strengthened structural steel as the flight deck was also the strength deck. This reduced the size of the lift to being only able to accommodate folding aircraft, not fixed-wing aircraft. It is sometimes called "1.5in equivalent", but it was nevertheless strengthened steel - not armour.

- In the same way, US carriers didn't have "timber flight decks". Instead, the decks were largely sheets of 8lb (.2") mild steel plates supporting the teak planks arrayed on top.

- Stability in the armoured carriers was never “hellish”. The author fails in any way to substantiate this argument. All WW2 carriers suffered from growing weights of anti-aircraft batteries and the aircraft they carried. The Illustrious class not particularly more nor less than others. However, ensuring that stability may have been a 'hellish' experience for the naval architects involved in the armoured carrier designs.

Why the RN worried about stability: HMS Victorious and the Home Fleet in the North Sea. Original British Path caption: Location Unknown / Unclear. Aircraft carrier and a battleship of the British Home Fleet being tossed abut in very heavy seas. Various shots of some of the ship's guns firing. Spitfires flying low overhead. Various shots of the sailors chipping the ice from decks and guns - ice all over.

One of the Implacable sub-class punches through a swell in 1945 - identifiable by the conformal recesses holding the 4.5in turrets on the side of the flight deck.

- Air Group capability was comparatively small: Correct.

But the attempt to paint the Illustrious class as one quarter to one third the number of its US contemporaries is a misrepresentation. First, its contemporaries were the Yorktowns - not the Essexes. Second, the Illustrious type only carried 32 aircraft in 1940: The numbers operated grew steadily.

Deck parks would – and did - boost the number of aircraft operated on the first three Illustrious class ships to more than 55 machines by 1943, both in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific, when the aircraft were available.

But there is no denying the "first batch" Illustrious class had a small air group. This was a doctrine decision that was accepted as a mistake by the RN pre-war, prompting design revisions to Indomitable, Implacable and Indefatigable. But the difference was not as dramatic as the author makes out.

The fleet support auxiliary carrier, HMS Unicorn.

Apples with apples: USS Yorktown during the battle of Coral Sea carried 53 *operational* aircraft. After the Coral Sea a review allocated 88 aircraft to the carrier. But only 66 were to be operational (deck park and hangar, folding and non-folding). The remainder were in a “broken-down” state and/or suspended as spares from the hangar ceiling. In Pedestal (roughly same time frame), Indomitable had 51 (folding and non-folding) aircraft and Victorious 40 (folding and non-folding).

As always: Doctrine evolves with experience. The much bigger USS Lexington submitted an Action Report for September 1943 in which the crew recommended doing away with spares stowage in the overheads and crated, and warned that its active complement of 36x F6Fs (folding), 18x TBFs and 35x SBDs presented dangerous overcrowding difficulties.

Then there's an example of the aforementioned "complexity". HMS Unicorn. From the outset, it was intended that each group of three Illustrious-type armoured carrier be supported by a fleet auxiliary carrier of the Unicorn class. These provided spares, maintenance and repair facilities - as well as a reserve flight deck and extra fleet support facilities (fighter direction as well as limited anti submarine / CAP operations). The USN never included such auxiliaries in its 1930s doctrine - instead preferring to include all this functionality in larger, less protected, hulls.

The US went the way it did because they had plenty of aircraft, used deck parks and envisaged launching mass strikes. They were able to base carrier defense on having fighters. The British were hobbled by the RAF that allocated few resources to the FAA, so the carriers had few and obsolete fighters. They had to build their carriers to take damage.

Partially correct, but incomplete.

The RAF/RN and the United States navy came to doubt naval fighter effectiveness in the 1930s after extensive fleet anti-aircraft tests (including Queen Bee radio-controlled drone exercises in the case of the British and a more capable dive-bombing drone in the case of the USN). These demonstrated fighters were not given enough time via visual warnings to conduct effective interceptions against increasingly fast bombers.

The emergence of radar and fighter direction – developed aboard HMS Ark Royal in combat off Norway from April 1940 – suddenly restored the effectiveness of fighter patrols and interceptions.

Also, in 1940 it was the USN which had obsolete fighter aircraft (The F3F “Flying Barrel” biplane) whereas the British had the Fulmar (The true contemporary of the Fulmar was the diminutive F2A Brewster "Buffalo" of which only 40 or so were accepted into active USN service). Those who point to the Sea Gladiator as an indication of carrier-borne obsolescence are simply muddying the waters: These went into service about the same time as the USN's F3F biplanes - and those remained the USN's front-line fighter until 1941. Only a handful of the emergency program Sea Gladiator land-base defence and training aircraft ever went to sea, and those few that did so in the Mediterranean were requisitioned by HMS Eagle's commander - not assigned.

This slender lead, however, was rapidly lost due to development cancellations and delays (hitting the Firebrand, Firefly and Barracuda) due to the emergency programs put in place to support the RAF's desperate defence of the Home Islands during the Battle of Britain. That carrier aviation doctrine also went awry in the 1930s is also undeniable - resulting in the specification failures that were the Skua, Roc, Firebrand and Barracuda. The Firefly, however, successfully went on to become the precursor to several decades of dual-seat fighter-attack aircraft (variable geometry and all).

Nevertheless, the struggle to build aircraft capable of mixing it with their land-based counterparts was a problem faced by all carrier powers in the 1930s. A measure of success was only achieved with the 1943 introduction of the Hellcat, Corsair and Seafire on behalf of the allies. The Japanese Zero achieved this goal in 1941 and 1942.

It's a struggle still evident today - if you watch the debate surrounding the 'jack of all trades' F-35 Strike Fighter.

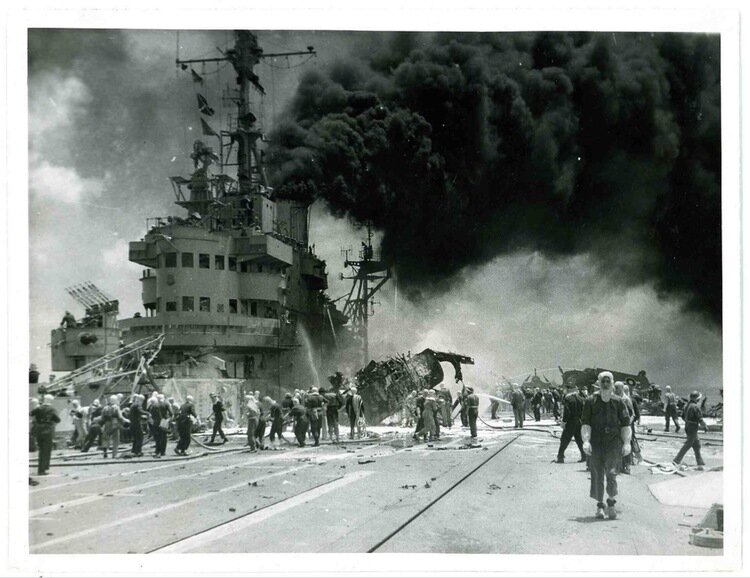

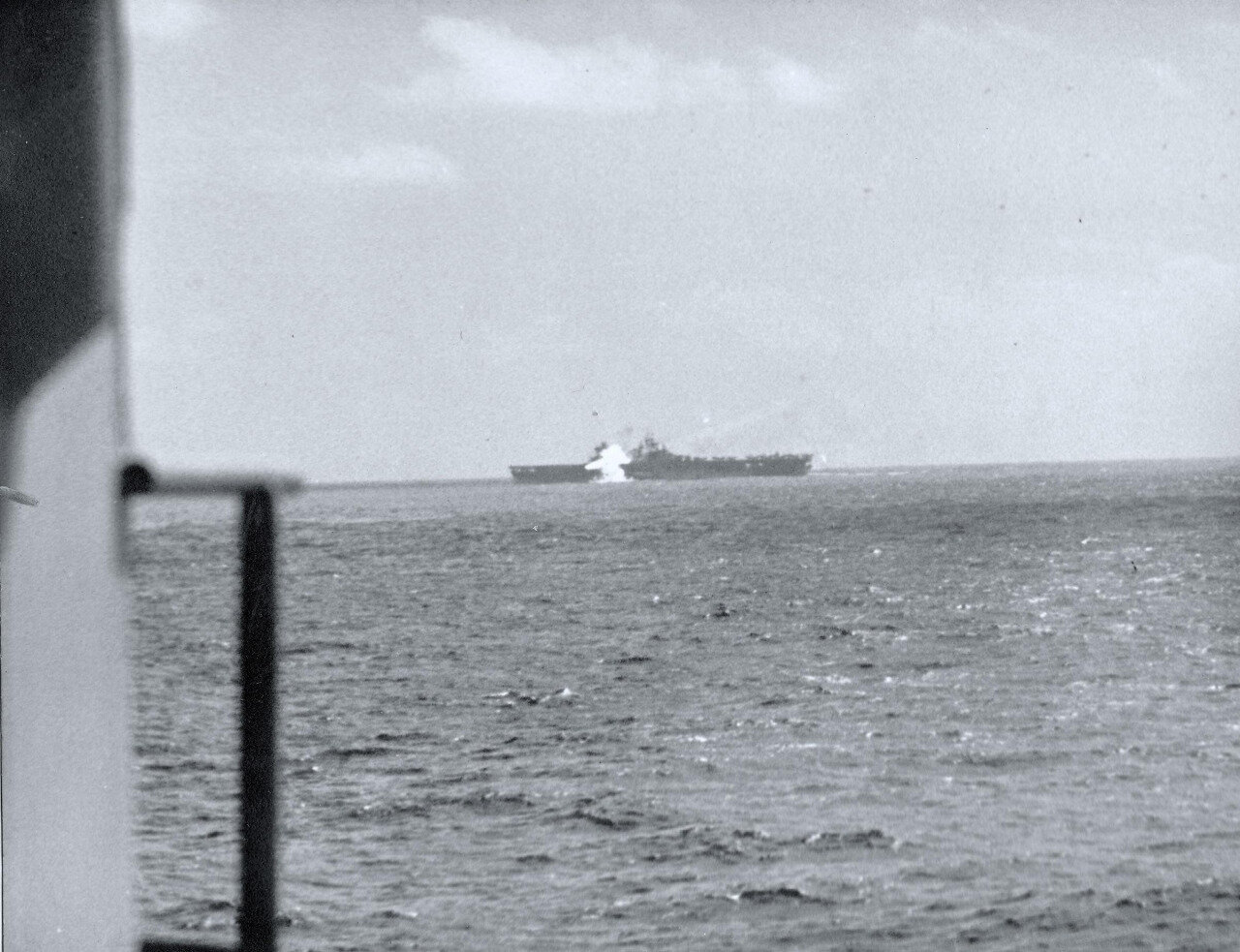

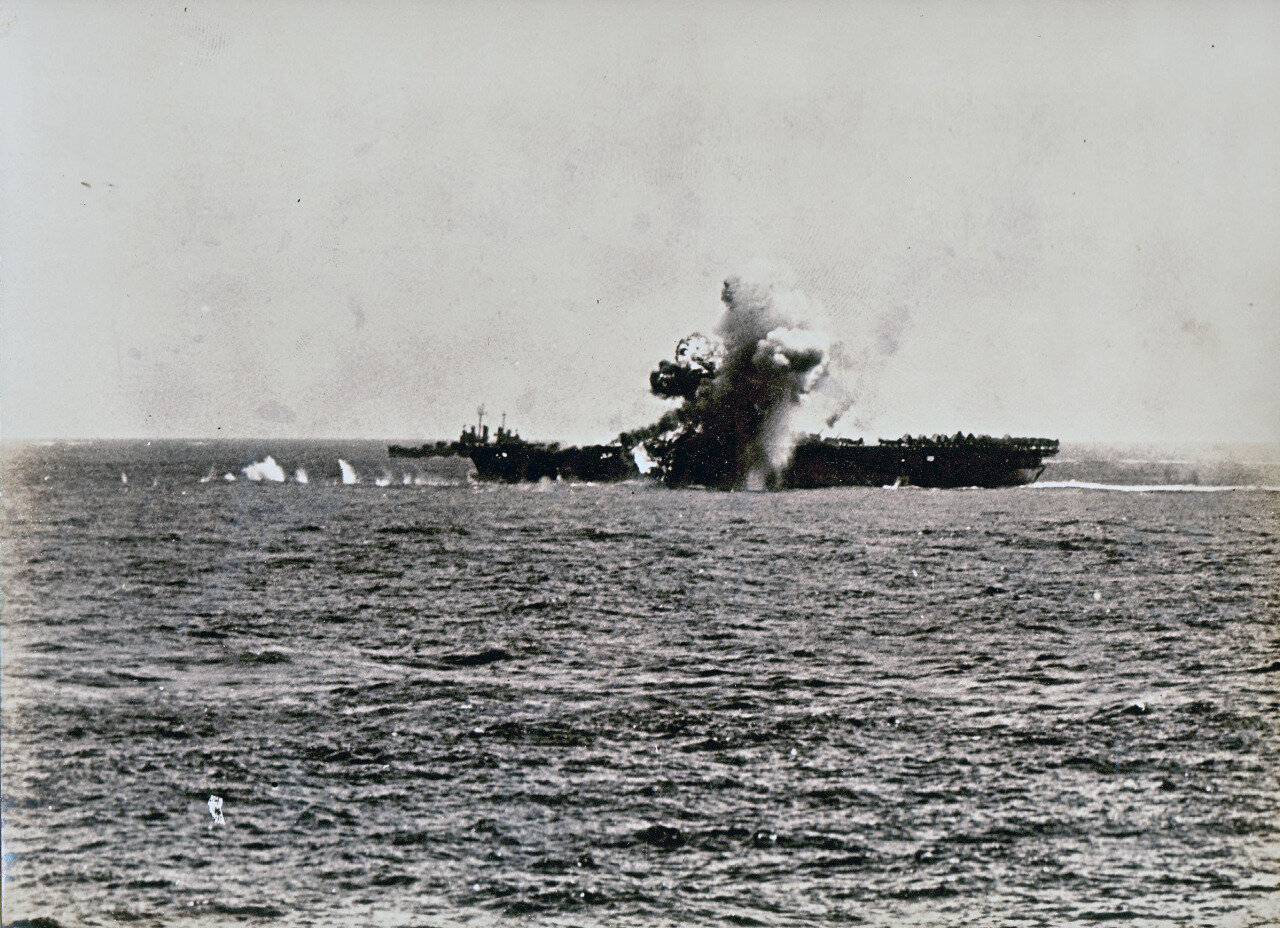

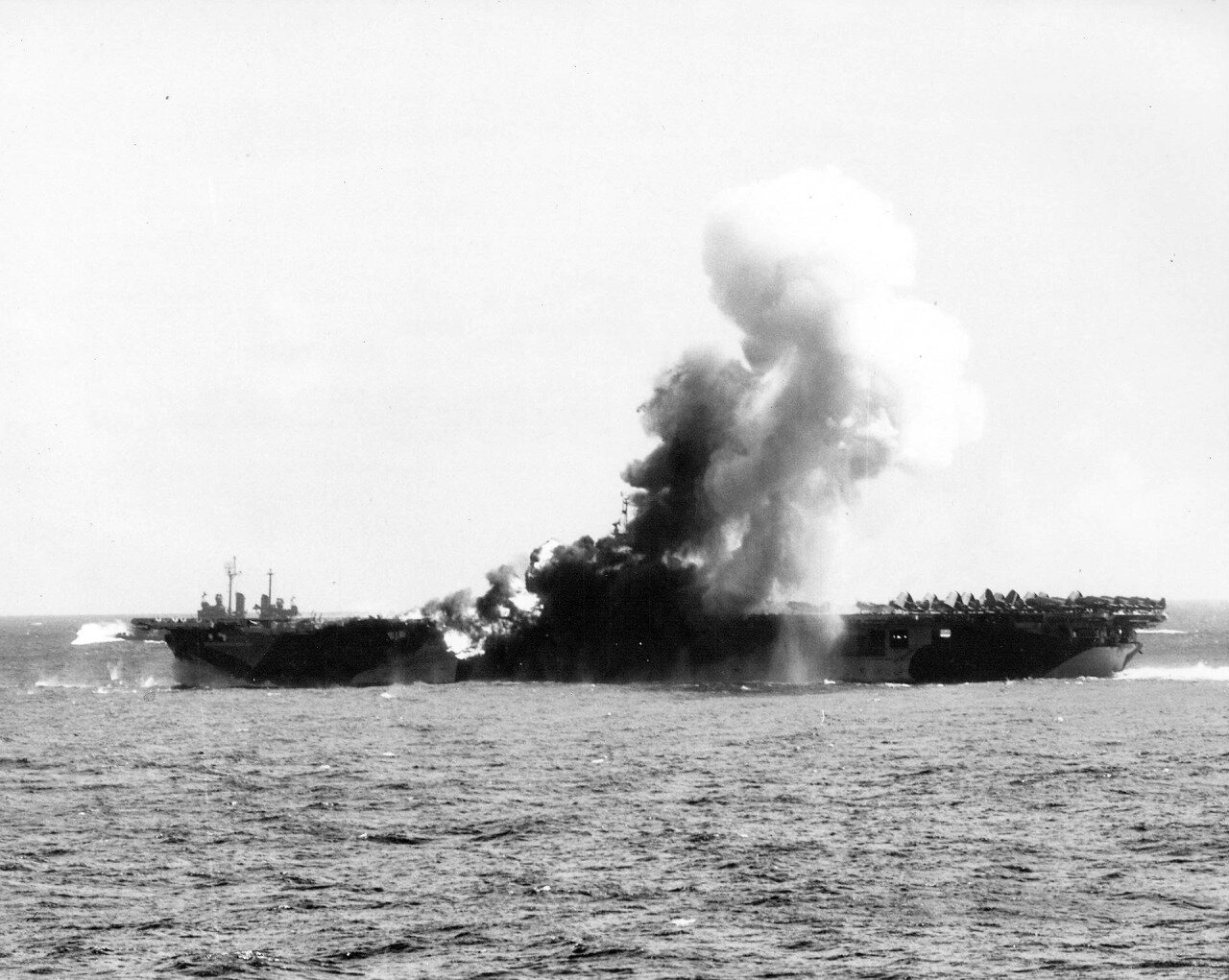

The explosion and fire aboard USS Bunker Hill after a kamikaze struck the centre of the flight deck.

The explosion and fire aboard HMS Formidable after a kamikaze struck the centre of the flight deck.

In fact, the British designs failed. Off Okinawa, the resistance of the British carriers seemed impressive but in reality the damage they took was severe.

An assertion the author does not even attempt to substantiate.

- How does Slade reconcile the above with the armoured carriers’ ability to stay on station? These ships were not “mission killed” (beyond a few hours) as were the wooden flattops. Their damage was able to be “patched up” sufficiently to remain on station and wait for more substantive work to be completed at the next scheduled docking opportunity. Is this not an ideal outcome for a warship?

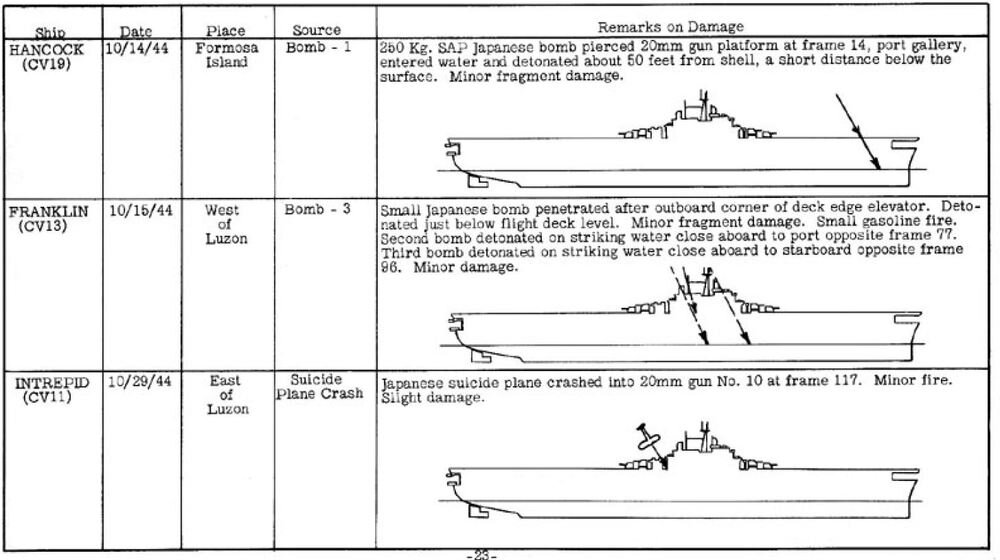

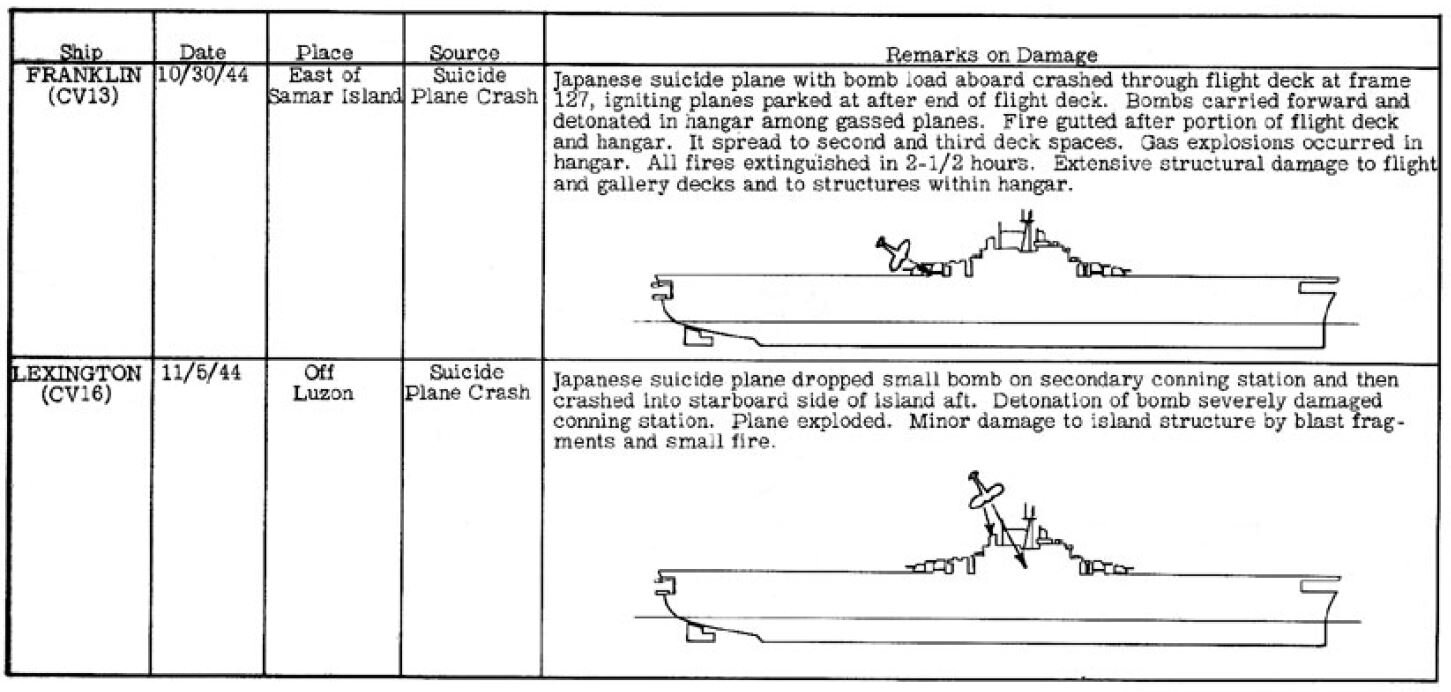

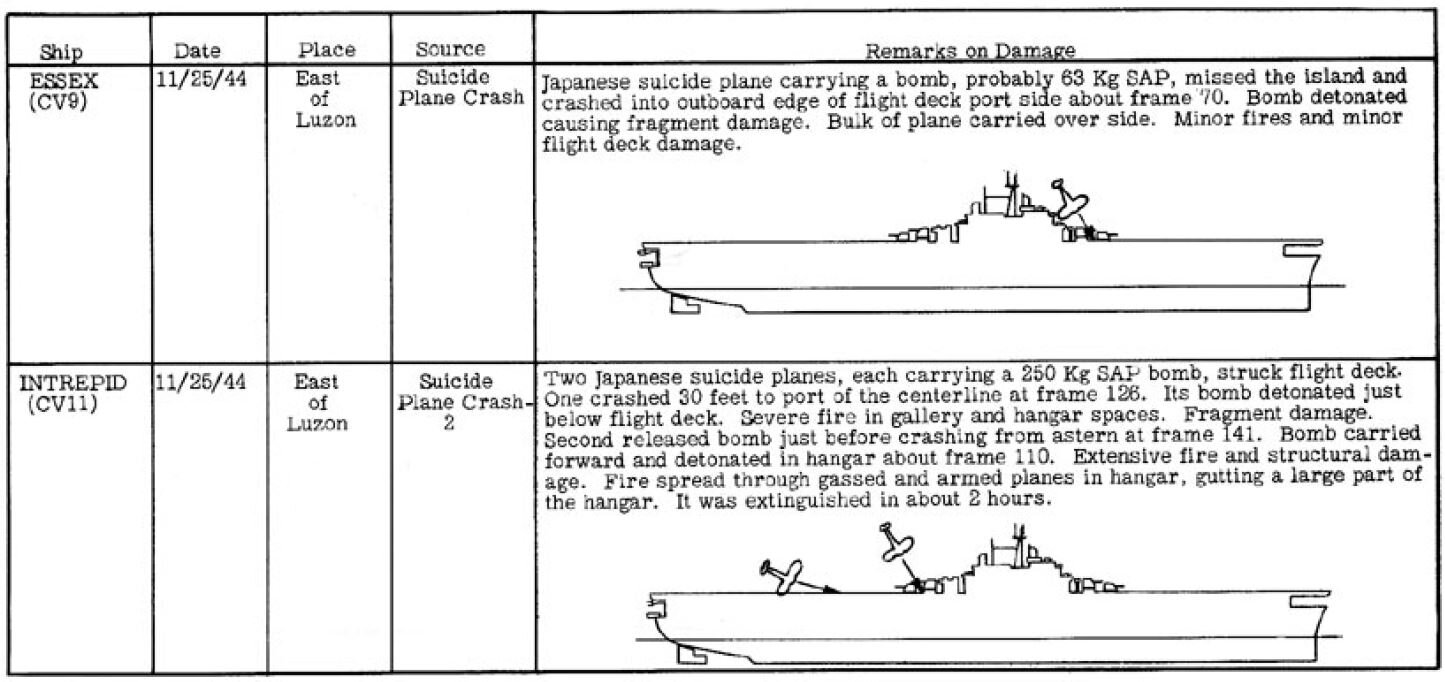

- One would expect serious damage from a 550lb (250kg) hit and a crashing aircraft loaded with ammunition and fuel. But worse than comparative strikes on US carriers? A simple comparison of details (such as the kamikaze/bomb hits taken by HMS Formidable to those taken by USS Franklin, Bunker Hill, Intrepid etc) may weaken this position.

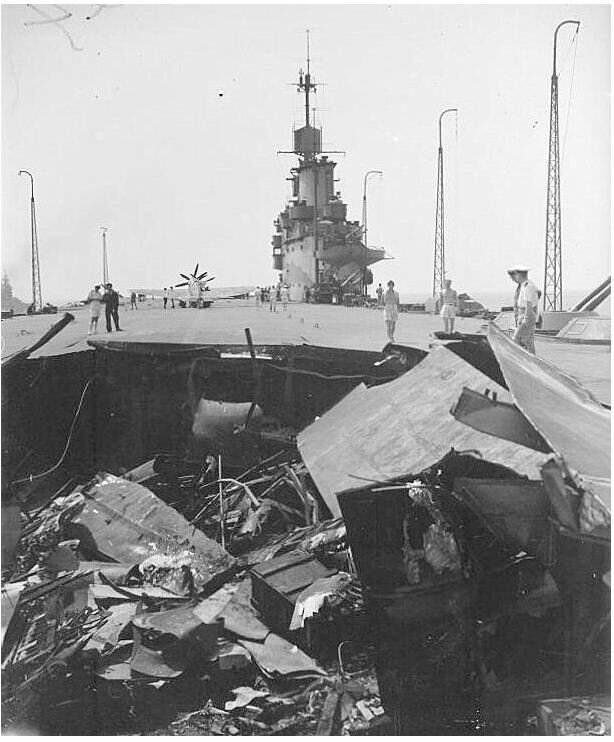

Damage to HMS Formidable's deck after the impact of a 550lb-bomb-carrying Kamikaze amidships. The exploding bomb and burning fuel killed nine and put the carrier out of action for six hours.

Damage to USS Bunker Hill's deck after the impact of a 550lb-bomb-carrying Kamikaze amidships. The exploding bomb and burning fuel killed 389 and put the carrier out of action for four months.

Having the hangar inside the hull girder made the hull structure weak and the ships were deformed by comparatively minor damage.

- Slade offers no technical justification for this assertion. British World War II era naval architect David K Brown states in his books that the flight-deck-as-strength-deck offered advantages in strength and weight.

- The structural damage Slade may be referring to is likely to be that sustained from the 2200lb (1000kg) bomb hits sustained by Illustrious and Formidable in the Mediterranean. These bombs were in excess of their designed optimal flightdeck armour resistance (550lbs/250kg) and far heavier in penetrative and explosive power than the bombs which struck the US carriers. The 2200lb (1000kg) weapons of the Luftwaffe did not induce "minor" damage.

BOMB WEIGHTS

X Fliegerkorps documents list the following bombs as having been deployed against HMS Illustrious during the January 10, 1941, Excess convoy operations:

3x SC1800 (4000lb) “Satan” / 1080kg TNT

9x SC1000 (2200lb) “Herman” / 600kg TNT

61x SD1000 (2200lb)*

”Large number”x SC250 (550lb) / 130kg TNT

* The SD (semi-armour piercing)1000 does not appear in official wartime munitions catalogues or summaries. It may, however, been a Luftwaffe “common usage” term applied to the PC (armour piercing) 1000.

61x PC1000 (2200lb) “Esau” / 160kg TNT

- Illustrious sustained below-waterline structural damage from a near-miss kamikaze in 1945. This re-opened wounds from at least three near-misses in the same area in 1941.

- HMS Formidable sustained serious below-waterline damage when hit / near missed by a 2200lbs bomb in the stern in May 1941. The shockwave did whiplash the hull.

- Below-flight deck structural beams were depressed by the Kamikaze hits on Formidable and Indefatigable. These did not impair the ships’ survivability or operations, and were made good upon return to Leyte and Sydney. Nevertheless, FAA pilots would often joke about Formidable's and Illustrious's "undulating" flight decks for the remainder of those ships' careers.

Note how quickly nearly all the armored carriers were scrapped postwar - surveys showed they had irreparable hull damage. In contrast, the Essex's, which suffered much more severe damage, lasted for decades

Another assertion the author does not even attempt to substantiate. Which severely damaged US carriers served decades after the war? Most seem to have been scrapped or placed in permanent reserve. The truth is, only one 'lasted for decades': USS Intrepid.

- Yes, the armoured carriers were surveyed post-war. As a result of these surveys, plans were drawn up to rebuild virtually all of them. These plans were abandoned due to Britain’s economic circumstances – rebuilding the infrastructure damage of being in the “front line” and repaying wartime debts was a greater impediment than expected. The armoured carriers lost a political war. Not a shooting war.

- Slade misleads the reader through his comparison to the Essexes. He also fails to mention the severely damaged USS Franklin and USS Bunker Hill were never restored to full active service post-war, and were never upgraded as were some of the other Essex class ships. Was this because of the “economic unviability” of their condition?

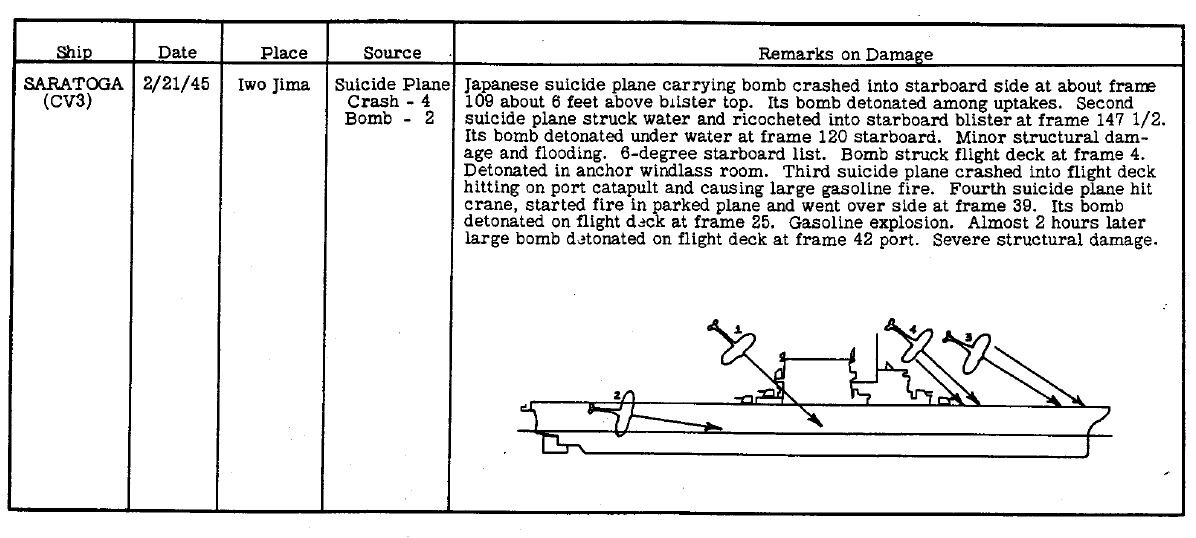

- Apples with apples: Enterprise and Saratoga, both treaty ships which had long and hard war careers, were also “discarded” quickly after the war. Does this also make them design failures?

Of the British armored carriers, Formidable and Illustrious were write-offs due to war damage. By the end of the war, Illustrious was in very poor condition; her centerline shaft was history due to structural deformation and her machinery was shot.

- Illustrious had been at war since mid-1940 and Victorious and Formidable since early 1941. Naturally, they had been “used” much harder than the Essexes that only joined the fight in mid-1943-45. Of course they served shorter combat careers (many not more than one operational war deployment). So it is natural for the Illustrious-class post-war condition to be poorer than the Essexes.

A more accurate 'tour of duty' comparison would be with the two surviving pre-war treaty ships - Enterprise and Saratoga.

- The unique circumstances of Illustrious’s battle damage has already been referred to (but not mentioned by Slade). Her centreline shaft had to be cut away in 1945 to reduce vibrations. Ironically, it was a US solution for severe vibrations in its own warships that was applied in late 1945 to fix Illustrious - a five-bladed propeller was affixed to her repaired centre shaft. Vibrations returned about three years later due to wear on the wing shafts.

- The Essex class never sustained bomb damage directly comparable to that received by HMS Illustrious (assessed as two550lb (250kg), four 1100lb (550kg) and one 2200lb (1000kg) ), or HMS Formidable (two 2200lbs (1000kg) ). Yet USS Franklin and USS Bunker Hill were laid-up post war after one or two 550lb (250kg) hits.

Formidable had raped herself when a Firefly (sic – aircraft that caused the damage was actually a Corsair) rolled off a lift and raked the hangar with 20 mm gunfire. This started a very bad fire which was contained within the hangar and acted like a furnace. The heat deformed the hull and that was it.

This is an unfortunately persistent falsehood. Everything about this statement – apart from the fact that there was a serious hangar fire – is incorrect.

Norman Friedman mentions this, in an unattributed manner, in his otherwise excellent book British Carrier Aviation (though he blames a Corsair). But no historical record substantiates this tale.

The only comparable incident was an accidental hangar fire aboard HMS Formidable on May 18, 1945.

- The British Firefly is the subject of a false rape accusation. The true Okinawa rapist was a US citizen – a Corsair. Formidable never carried the Firefly on active service.

- The calibre of weapon was 50cal, not 20mm.

- The gunfire – caused by a fault in the Corsair’s electrical system under the hands of a mechanic, not by falling off an elevator - exploded a US-built Avenger, which started the fire in the crowded hangar.

- About 5 aircraft were destroyed. Up to 30 were "written-off" due to fears of corrosive damage from the salt water sprays and foam suppressants. Three of these were repaired by Formidable's own mechanics. The remainder were flown off to escort carriers to be delivered to HMS Unicorn for reconditioning.

- Oddly enough, this incident is also often cited as a demonstration of the advantages of the British fire-fighting and damage control design... that the fire was contained within 15 and extinguished after 55 minutes - before it could do catastrophic damage - and that there were no casualties. The effect of this hangar fire simply cannot be compared to that experienced by Franklin, Bunker Hill, Hancock etc.

- The fire was largely contained by damage control crews before an over-zealous crewman opened the hangar spray valves because the fire curtains had been jammed by an earlier kamikaze attack. Formidable never experienced the hours-long furnace-like conditions that distorted Franklin and Bunker Hill’s structures. HMS Illustrious, however, did.

- That the heat deformed the hull… possibly. This happens with most serious fires on most warships. But Formidable, Victorious, Implacable did not experience bomb induced fires like Franklin or Bunker Hill due to their passive defence designs. That Formidable returned to the war zone two days after a serious accidental hangar fire and continued to act as an operational flight deck does speak somewhat for itself… Formidable also contributed to the fight off the coast of Japan little more than a month later, after rushed repairs to the armour plate and structural beams in Sydney.

- Most references to Formidable's post-war damage that I can find point to the cost of rewiring the ship (due to corrosion from the hangar salt water sprayers having being activated on several occasions). There was, however, long term structural damage from the many near-misses and the 2200lb hits in the bow and stern. And yes, the quickly patched-up flight deck remained 'bumpy'. As this armoured plate was also structural, it is technically correct to say the ship was 'structurally deformed'

(Since this debunk was first written, several sites have adjusted their unsourced claim about this accident to concede it was a Corsair and to assert it happened "post-war". This is impossible. HMS Formidable landed her air group immediately upon the end of the war. She was used as a repatriation transport in the Pacific and then between Australia and Britain before being paid off into reserve - awaiting a deep repair and reconstruction that never happened. There were never any post-war air operations, yet alone with 20mm variant Corsairs)

Indomitable was actually used in the post-war fleet and was modernized (lightly). In 1951 she had a gasoline explosion in her hangar deck. This was actually quite minor (an Essex would have shrugged it off) but the fact it was contained and was within the hull girder caused severe damage. She was patched with concrete for the Coronation Review, then scrapped… After her 1950 gasoline explosion (shortly after she finished her refit), she was completely useless and had to be towed to Spithead for the Coronation Review.

Again, the actual damage reports from this explosion (in 1953, not the incorrect 1950 and 1951 dates given by Slade) don’t seem to paint quite so severe a picture when examined:

- The explosion was in the vicinity of the starboard oiling sponson and blacksmith’s workshop. I'm not certain, but this does not appear to have been substantially within the hull girder.

- The fire – which spread to the hangar - was out within 45 minutes. But the explosion did separate the 1.5in side-armour plates to the hangar. And this may have had structural implications as it formed part of the box hangar.

- It was serious damage, yes. Significantly, it was not severe enough to halt the ship’s Mediterranean deployment and participation in flying exercises (so not completely useless?).

- Indomitable proceeded to the Coronation review under her own steam (yes, with a thick layer of fresh paint and some 300 crew from a suddenly vacant destroyer). She was not towed.

- What a glance at the associated paperwork reveals is Britain’s inability to pay for post-war reconstruction and a large-scale navy. Her damage was seen as a good excuse to bring forward an already telegraphed fleet reduction.

The Victorious conversion was one of those tragedies that was almost comical. .. The rebuild was fiendishly expensive, largely because the flight deck was the hangar deck and partly due to idiotically bad project planning.

- This point, on its own, is valid. A pity it is irrelevant. This does not add to the armoured carrier debate. It does seek to associate ridicule with an unrelated conversion project involving an armoured carrier with the debate over their service effectiveness.

It is also interesting to note that the Essex design also failed to anticipate the needs of heavy jet aircraft and their structurally weak flight flight decks saw most of them rapidly relegated to second-line service. Yes, their light structural flight deck allowed for easier and cheaper modification. But this had limited utility, so it was applied to very few ships.

Another point which should be brought up is that the armored box hangar on the RN CV's was restricted to a height of 16 feet maximum and was as low as 14 feet in the upper hangars on the Indomitable, Implacable and Indefatigable. This restricted the use of the F4U Corsair fighter in the 14 feet hangars. This also hampered the usefulness of the British carriers postwar as aircraft grew in size. By contrast, the USN carriers had a hangar clear height of 20 feet in the Lexington class, 17 feet 3 inches in the Yorktown class and 17 feet 6 inches in the Essex class. This greater height allowed the Essex class to easily adapt to the much larger postwar jet aircraft.

So far this is the most valid and realistic issue raised. It is generally uncontested (though Slade once again has a fact wrong: Implacable and Indefatigable had both their upper and lower hangars at 14ft. Indomitable had her upper hangar at 14ft, and her lower half-hanger at 16ft)

-Apples with apples: Enterprise, the only Yorktown class carrier to survive the war, was not part of the US post-war upgrade program. Her 17ft3in hangar and timber flight deck didn’t save her from the consideration that she had been “hard worn” from her battle damage and long active service.

We also have to be very careful when looking at apparent ship histories in the 1945 - 1955 period. There is a lot of statistical deceit used here (Eric Grove in "Vanguard to Trident" makes an eye-opening read).

As do Slade and Worth’s essays. It is a pity Slade does not take his own advice.

The post-war element of this debate essentially “moves the goalposts”. It shifts the debate away from the context of combat effectiveness to one of cost effectiveness.

"Vanguard to Trident", as you can tell by the name, is the post-war period.

1945-1955 was a period of relative peace (Korea accepted). It is a period dictated by economic expansion (for the US) and contraction (for the UK).

I’ll restrain my debate to whether or not the armoured carriers more effective in the combat circumstances they were designed for, not more survivable in a deteriorating political and economic battle nobody could predict when they were built.

Suffice to say, "Nelson to Vanguard", by RN naval architect D.K. Brown (whose career began in WWII), paints a much more balanced picture of their war performance. (The details this book contains about UK versus US constructor profit margins is a real eye-opener).

It is also not true that the Illustrious class carriers were worn out by hard war service. The last pair were only used for a couple of years and didn't work that hard. They certainly did not do the long deployments undertaken by the US carriers during the war.

Simply wrong.

- Slade validly points out the last pair (laid down in 1939 but not completed until 1943/44 due to Churchill’s fascination with battleships, prioritisation of anti-submarine escorts and war shortages of armour and labour) were not worn out by hard war service. Most Essexes, for example, experienced even shorter tours of duty.

- But why dismiss the long and hard career of Illustrious (1940), Formidable and Victorious (1941) and Indomitable (1942)? Elsewhere, Slade goes to great pains to emphasise the lasting damage these ships suffered from their active service...

- The deployments of the armoured carriers were extensive and long. Yes, they operated from “advance bases” such as Alexandria, Malta, Gibraltar and Ceylon. But few of these had complete shipyard facilities (some were better than others, but none could be compared to, say, Pearl or Portsmouth).

- The deployment of the British Pacific Fleet – which had its primary supply chain reaching half-a-world away to Britain – was in many ways longer than any undertaken by the US carriers. Armoured carriers were also stationed forward in Ceylon from 1942.

- Ships such as Illustrious and Formidable undertook considerable deployments between major refits. This was one of the issues facing Illustrious in 1945 – she was only in the British Pacific Fleet because of delays in getting Formidable and Implacable to the theatre. She had been scheduled to be in dry-dock undergoing deep maintenance.

USS Pittsburgh lost her bow in a typhoon in June 1945.

Indefatigable and Implacable were badly built (as were most British wartime ships - Admiralty records related to planned reconstructions quoted in Vanguard to Trident implicitly give war-built cruisers a life of only ten years). No criticism intended there - emphasis was on quantity rather than quality.

A possibly correct observation (without substantiation) for a nation facing constant air attack and attempted submarine blockade.

- What relevance does the life-span of the emergency build cruisers have to do with the armoured carriers? Especially as he takes no effort to compare with the effective life-span of the US war-build cruisers.

- For this argument to be effective, its detail needs to be expanded considerably. On the surface, it appears very weak. For example, all but one of the dangerously top-heavy Cleveland class had been laid-up before the 1950 Korean War. Out of 29 completed, only six were rebuilt as missile cruisers.

- It is also interesting to note that no RN war-build cruiser suffered structural failures in hurricanes or typhoons as severe as USN cruisers did during the war.

The suggestion that they are a response to the UK armored carrier designs is largely a myth - the discussions that lead to the Midway's actually predate the Illustrious class.

It is correct to say the CVB was not a “response” to the UK armoured carrier designs. However, there is much documentation available about the influence of the RN. US Navy engineers examined the ships closely when in US dockyards for repair, and these reports influenced the USN design bureaus. (USS Franklin’s War Damage Report is one such giveaway).

However, yes, the US did studies into armoured flight deck designs in the 1930s. It was one of two "solutions" to the problem being presented by the era's war games: The first strike (whatever it size) would sink solo or paired carriers.

The solutions: Make the carriers tougher or build more decks. The 1930s USN came down in favour of a doctrine supporting many expendable flight decks. The US armoured carrier concept designs of this era have little resemblance to the Midways that actually emerged (nor does the Illustrious for that matter). But the reasoning does.

Don't get me wrong; the strategic and operational logic that resulted in the Illustrious class was (for the Royal Navy) quite correct - the vulnerability of the ships to internal damage was unexpected and surprising. That vulnerability made their designs essentially failures since the sacrifices made to give them their heavy protection were not fully justified by their performance.

Vulnerability to internal damage? Where has this been established, substantiated or even sourced?

I have reproduced as much detail on www.armouredcarriers.com from the battle damage reports of the Illustrious class as I can gather. Compare and contrast these with the US battle damage reports freely available on the web. Compare like hit with like hit (mostly restricted to the 550lb bombs). Decide for yourselves.

Here Slade assumes his argument that the ships were not rebuilt during Britiain's post-war recession makes the Illustrious class a failure.

An economic failure in recession conditions?

Yes.

Can this be linked to whether or not they were a design success in combat conditions?

No.

- Slade has so far failed to establish the Illustrious class's internal damage "vulnerability" beyond simple assertion. They were hit by multiple heavy bombs and subject to a string of near-misses during their Mediterranean and Pacific campaigns. I suspect the Essexes and Yorktowns would have been "vulnerable" to internal damage from 2200lb bombs dropped by Stukas in the same manner they were vulnerable to low-penetration delivery of 500lbs bombs carried by kamikazes. The resulting fires etc would be a further compounding issue, as their battle damage reports show.

- Given Slade’s simplistic argument, one would have to assume USS Franklin and Bunker Hill, as well as Enterprise and Saratoga, were "economic write-offs" from their vulnerability to internal fires and light bomb / kamikaze hits. It would therefore follow, under such logic, that they would also have to be regarded as essential design failures…

And then there’s the opinion of her adversary:

“A few days later the Illustrious was sighted once more, this time in Alexandria, which she was thought to have reached under her own power. This failure caused great disappointment in Fliegerkorps X. These poor results were generally thought to be due to some special protection around the Carrier’s engines and her main installations, rendering the blast of the bombs ineffective. The SC1000 bombs which fell between the Carrier and the Quayside probably damaged the ship’s hull, but as she was no doubt equipped with strong bulkheads, she could keep afloat in spite of being partly flooded and lying low in the water (as seen from the shorter shadow cast).”

The real point of difference is that the Essex class had an external hangar, that is, the hangar is located outside the ship's girder while the Illustrious class had an internal hangar; that is, the hangar is contained within the ship's girder.

An external hangar offers large side openings so that aircraft can be warmed up on the hangar deck, loading and unloading aircraft is made easier, underway replenishment becomes easier and safer and, most importantly, flight deck damage and hangar deck fires are outside the main hull and therefore of less structural consequence. Deck edge lifts are also very easy to install.

A valid design point. But Slade doesn't do the full compare/contrast thing.

- Underway replenishment was not important in the Atlantic and Mediterranean theatres. Once it became important, it was relatively easily accommodated by the multitude of sponsons protruding from the side of the RN carrier hulls. This was an issue of doctrine. Not design.

- Deck-edge lifts and large side openings made ships prone to trivial damage such as storms, bomb or shell splinters - and possibly even light-arms fire.

- Deck-edge lifts were applied to the follow-up armoured box Audacious class.

- He fails to relate that many damaged US carriers were – at best - only able to offer very limited flight operations as their aircraft operating facilities had been destroyed/damaged in the kamikaze attacks. In several cases, these "flight operations" were simply flying off aircraft already on deck to bolster remaining operational carriers as the damaged carrier headed for harbour.

- No British hangar was even mildly affected by kamikaze/Japanese bomb hits. (In Indefatigable and Formidable, a small quantity of burning aviation fuel from the flight deck leaked through a popped rivet or a small spall hole in the armour, but this was contained by damage control before damage was done).

- The only armoured carrier to have had battle damage to the hangar space was Illustrious when hit by a 2200lb bomb on the armoured deck and three bombs (550lb) on the aft-lift. The manner in which this damage was largely restricted to the hangar (as designed) saved the ship.

- Formidable was struck by a 2200lbs (1000kg) bomb in the bow and stern in 1941. The enclosed armoured hangar prevented this damage from affecting the aircraft and stores there.

- Indomitable was struck by two bombs (probably 550lb "burster" bombs, possibly 1100lbs SAP), one forward, one aft. The hangar was breached in the unarmoured forward lift space, but the damage to the hangar itself was negligible. The aft hangar space was unaffected.

In the Forrestal and after, the flight deck is the strength deck, protection considerations had no influence whatsoever on the flight deck design.

- Once again, documented USN analysis of battle damage (such as the commonly available and comprehensive USS Franklin Battle Damage Report) reveal the opposite of this assertion. In the same way RN experience prompted the armouring of Midway, protection was a major consideration in the Forrestal’s flight deck design because experience with USS Franklin and Bunker Hill showed such protection was necessary to separate damage on the flight deck from the volatile hangar beneath.

In fact, the Illustrious class are so well designed in weight economy terms that even today it is impossible to find areas to make additional savings.

- Which emphasises an imperative which Slade keeps ignoring: The Illustrious class was built under 1930s limitation treaties. The Essexes were released from these considerations because of the outbreak of war (yes, even 1000 tons extra makes a major difference). The Midway class was completely unfettered from such restraints. Forrestal belongs to a completely different era. So the closest “apple” in this debate can only really be the Yorktowns.

Unfortunately, there was a hidden problem that no one realized at that time. The hangar forms a large open void in the ship's hull girder. When faced with shock, this allows the girder to deform and, once deformed, the damage is irreversible. The gravity of the shock problem only became apparent with the magnetic mines used in 1939 and when the ships started taking near misses. In effect, the hulls became progressively twisted and rippled as damage mounted up. This killed Formidable and Illustrious

This is the most specific part of Slade’s argument so far.

It remains unsubstantiated. And his argument doesn't add up.

What he totally fails to do is examine exactly what it took to “kill” Formidable and Illustrious. It appears to have involved a considerable amount of high explosive being dumped on and around them. Neither were sunk or placed in severe danger of sinking.

The “kill” was ultimately an economic kill. Not a ship kill and in several cases not even a mission kill.

Magnetic mines were a serious threat. But none ever impacted the armoured carriers (or an Essex or Yorktown for that matter). So why he raises the subject is unknown. It was heavy ordnance delivered by land-based aircraft which created the bulk of near-miss "shocks" for the Illustrious family of ships.

Illustrious and Formidable continued to serve effectively for years under combat conditions after sustaining heavy battle damage. They were able to operate aircraft at enormous distances from their home ports. This they did with increased difficulty, but they were able to sustain their effort

We do not have comparable data for the USN carriers as they did not have that weight of ordnance dumped on or around them. However Saratoga, Franklin and Bunker Hill (as with true generation contemporary Enterprise) were also "killed" (according to Slade's own criteria) by the serious damage they sustained.

The British carriers never came under the weight of attack that the US carriers suffered and never took the same density of hits.

I guess if you only look at Okinawa, the above is arguably correct (though ignoring Operation Pedestal in August 1942 is a hard ask). And there is an element of statistical deceit is Slade’s claim – the British armoured carrier force was an equivalent to a US Task Group, not a full US Task Force).

The BPF’s Task Force 57 also operated as an independent Task Group, not three Task Groups in unison as did the USN off Okinawa.

To address this statistical deceit: The British Pacific Fleet force was four fleet carriers. The USN force was about 11-15 fleet carriers (depending on availability due to battle and storm damage) organised into a unified formation of three or four task groups of roughly four carriers. Divide those 11 into three and the number of attacks faced is still much greater, but not as dramatic as comparing four with 11.

Also, there had been a war outside the Pacific theatre. It had been raging since 1939.

Let’s try to put this in perspective:

- Weight of attack: Illustrious, January 9, 1941 (Operation Excess): Solo carrier versus 2 aircraft in wave 1, 70 + in wave 2, 12+ in wave 3, 20+ in wave 4, 17+ in wave 5, 2ish in wave 6. Then there was Indomitable and Victorious versus the 784 aircraft assembled by Germany and Italy for Operation Pedestal in August 1942…

- Density of hits. Mediterranean … two 550lb hits, five 1100lb hits, one 2200lb hit for Illustrious, two 2200lb/1100lb hits for Formidable, two 550lbs hits for Indomitable…

- Density of hits: At Okinawa: Three 550lbs bombs delivered squarely on the flight deck (One on Implacable, Formidable took two), three glancing blows (One on Indomitable, two for Victorious), several near-misses (Indomitable, Illustrious).

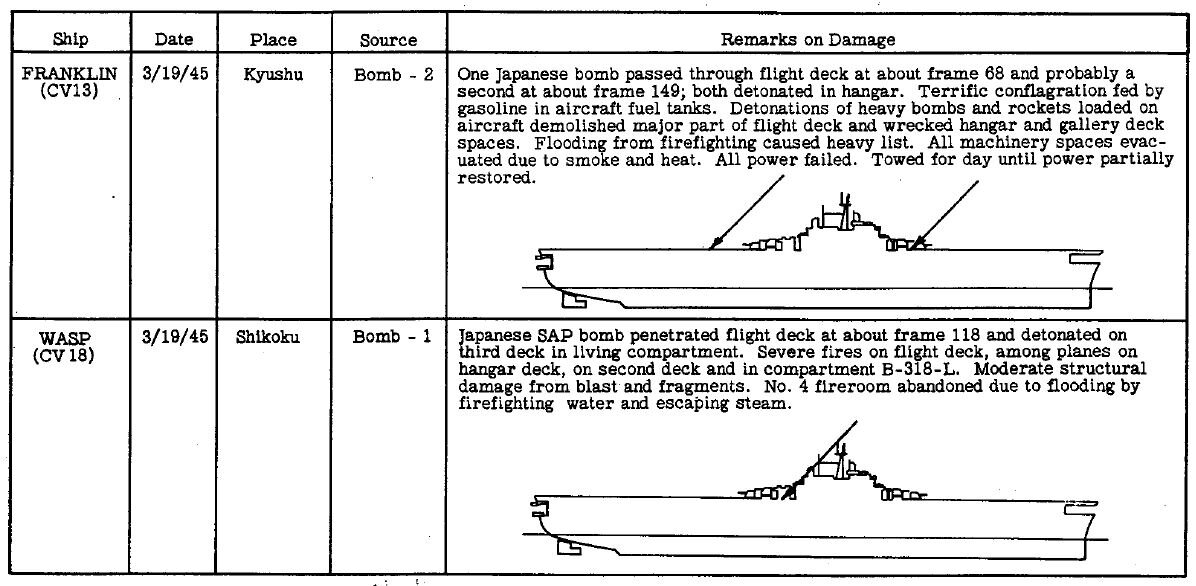

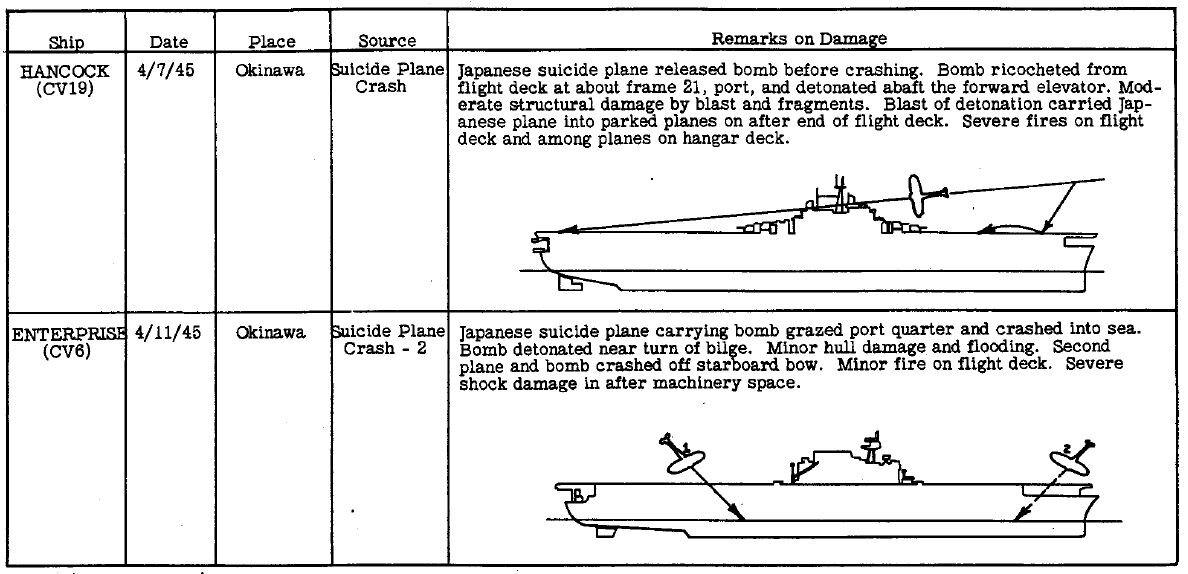

USS Franklin: one (or possibly two) 550lbs bombs delivered by non-kamikaze/dropped on the central section of her aircraft-crowded flight deck: 807 killed, 487 wounded. Withdrawn to the United States

HMS Formidable: One 550lbs bomb delivered by kamikaze/dropped on the (armoured) central section of her flight deck which was in the process of moving an aft deck park forward: Nine killed, about 50 wounded. Remained operational and on station. Still on station, Formidable was hit again several days later in almost the same spot in the center of her armoured deck. One person was killed. She remained on station.

- The reasons for the discrepancies in casualties and damage are many and varied. However, it can be correctly said that the armoured hangar largely restricted the damage to the deck itself and the aircraft on it. USS Franklin proved to be vulnerable to longer and more intense fires as her aircraft (and their ordnance) kept falling / blasting through her timber/light steel deck into the blazing inferno of the hangar below. The fuel, ordnance and molten aluminium from Formidable's burning aircraft did not penetrate the steel flight deck - thus preventing any chain reaction in the hangar.

Above: A sequence of photographs showing USS Essex being struck among anti-aircraft guns on the port edge of her clear forward flight deck by a D4Y Judy (with no bomb) about 12.56pm on 25 November, 1944, killing 15 and wounding 44. USS Essex was able to resume flight operations by 1.35pm. The death toll from this single unarmed kamikaze hit matched that from all the kamikaze strikes against RN carriers combined.

It is not immediately apparent, but most Kamikaze hits bounced off US carriers doing little or no damage - the ones that started the big fires were the exception.

Again, this begins to look a little weaker when you look at the actual examples. Glancing-blows by kamikazes did little damage to both US and British carriers. It is a weakness of the weapon system – the kamikaze – not a strength of the relative carriers.

- Indomitable and Victorious both had kamikaze’s “bounce” off them, doing negligible damage.

- The direct hits that started big fires on the flight decks of Indefatigable and Formidable also did (relatively) little damage.

- Slade does not appear to have looked at this very hard at all. What perpetuated the big fires on Franklin and Bunker Hill? Was it their hangar vulnerability to penetration by kamikaze and/or their bombs? Were the burning aircraft on the deck and the drop tanks and bombs they carried prevented from spreading? How do the fires from 550lbs bomb-carrying kamikazes on other carriers such as Intrepid and Enterprise compare with those on the armoured carriers?

A critical factor seems to have been deck parks - if the stricken carrier had deck-parked aircraft, she was in trouble regardless of where her hangar was.

- Assigning blame for US carrier damage to their aircraft on their decks is disingenuous: That is what carriers do - fly aircraft from a flight deck.

It is a function to be designed for.

Attempting to excuse the vulnerability of US carriers through the need to range aircraft before launching a strike is therefore a type of fallacious argument known as "special pleading".

- It's also a myth that the armoured carriers did not have deck parks when hit by kamikazes. The above sequence of photos for Formidable on May 4 demonstrates this. Deck parks were also present on Indefatigable when her armoured flight deck was struck, as was the case for Victorious and Formidable again on May 9. They were not as big as those on an Essex as the flight decks were not as big.

- British carriers and deck parks need to be clarified: While they didn’t often use deck parks in the North Atlantic because of the snow, ice and rough weather, they increasingly did so in the Mediterranean and Pacific from as early as 1942.

- The point of difference between British and US carriers is that fires did not transition from the flight deck to the hangar below in the Illustrious class - whether there was an extensive deck park (or ranged strike) or not.

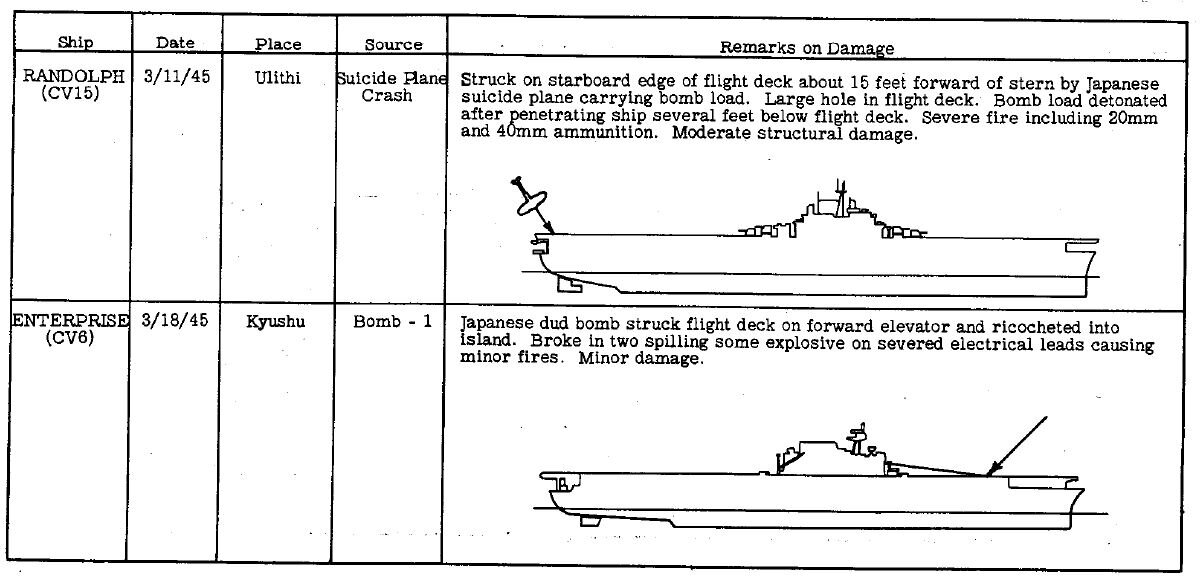

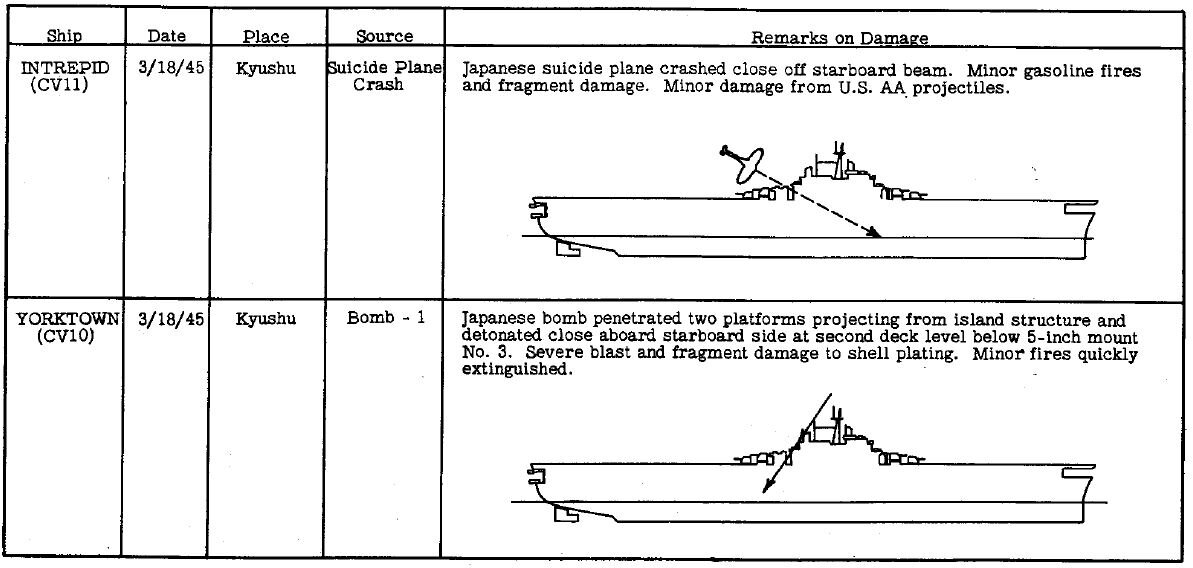

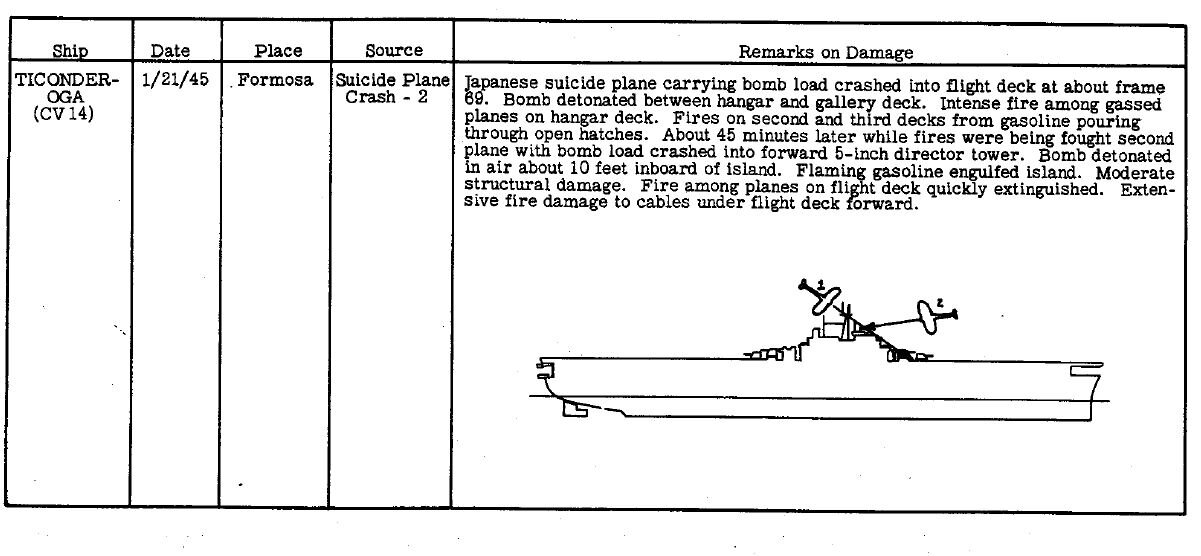

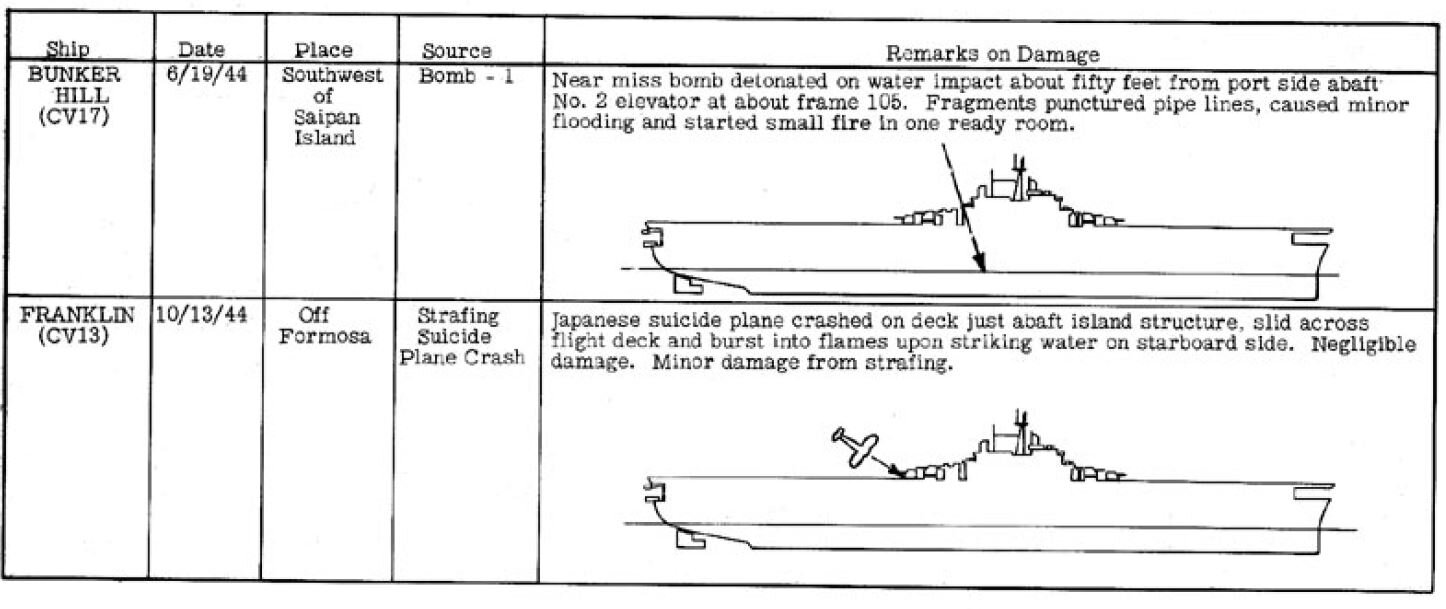

- The argument is also historically suspect: Some US carriers appear to have sustained little damage to kamikaze hits on deck parks. Some took severe damage with very few aircraft on deck. It would need much greater listing of all damage incidents to provide substantiation for this assertion. A good start point is the USN's own summary of kamikaze damage (I include a gallery of the carrier components above - so you can check for yourself)

The Armored Box: The War's Verdict

©2002 Richard Worth

The armor-box hangar, for all its legendary virtue, never justified the legend.

- A reading of the events surrounding Illustrious in January 1941, Formidable May 1941 and Indomitable + Victorious August 1942 could suggest otherwise

- As would a reading of the events surrounding Illustrious, Indefatigable, Formidable and Victorious during the British Pacific Fleet’s operations in Operation Iceberg, 1945.

Lift configuration, freeboard, habitability, ship’s speed - the box restricted them all. But the salient fact, overshadowing all others, was the limit it imposed on air complement.

Some valid points, some not quite so. Let’s look at them.

- Lift configuration: One at the front and one at the rear of the hangar. This is an optimal configuration that almost all designs utilise. However, other designs do add a low-efficiency third (mid-point) lift and others highly efficient (but vulnerable) external lifts.

The holes in the protective systems by these extra lifts were regarded as an unacceptable weakness in the Illustrious design, so, yes, it did reduce the speed of moving aircraft between decks somewhat. But their lifts were quite fast. Perhaps Worth is confusing the complicated lift arrangement of Ark Royal (not an armoured carrier).

- Freeboard: The first three armoured carriers were lower than the US carriers and their predecessor, Ark Royal. It certainly had no effect on ship stability, as can be directly compared to that of the US carriers in the typhoon which struck both types of carrier when they formedTask Force 37 in the war off Japan.

- It was the Essexes that experienced "hellish” stability (Slade’s word) due to wartime topweight growth, resulting in urgent remedial actions and operational orders to mitigate risks (touched on in the Franklin damage report). The Illustrious class had no such debilitating stability issues.

- Habitability: All pre-war ship designs suffered from severe overcrowding once expanded air groups and anti-aircraft gun armaments were added – including, for example, Enterprise. Comparing apples with oranges again, as the bigger Essex class had learnt from the experience gained in the Mediterranean and North Sea. Nevertheless, this still proved inadequate by 1945 and overcrowding is a common feature of all first-person accounts of service aboard these ships. But, yes, it was particularly bad aboard the "Batch I" Illustrious class and this - possibly more than deck and hangar space - was a major reason why these ships could only operate up to 57 aircraft.

- Ship’s speed: The Illustrious class had a top speed of about 30-31 knots (they never underwent full trials due to war conditions in British waters). Not as impressive as the US Essex in controlled speed trials performance, but somewhat similar once in real operational conditions. Also, speed is important for battleships, where one or two knots can make the difference between a good and fatal position. With carriers, it is much less relevant as their optimal range is determined by the range of their aircraft - not their guns. Wind over deck is important for aircraft, but one or two knots is not a decisive margin.

- Limitations on air complement: Accepted. It was also accepted as an issue by the RN even before the war started in 1939 with the modification of the design of Indomitable and the last two ships to incoprorate a second half-hangar. The RN's contemporary design to the Essex, the armoured-hangar Audacious class, had a similar air group. But the RN still regarded there to be a need for the ships to be able to survive in “close combat”, such as the Mediterranean, so compromise was regarded as necessary.

The small-group specification put the ships at an initial disadvantage, and the armor then canceled any hope for a remedy, cramping the hangars and reducing the space available for deck parks.

- Worth seems to assume that the armoured carriers only carried 33 aircraft. By the end of the war, the original smallest designs (Illustrious, Formidable and Victorious) were operating up to 57 aircraft.

- Implacable and Indefatigable were operating up to 85 aircraft - not as many as the Essex and Yorktown US fleet carriers, but still a useful figure. Again, potentially very interesting if we can establish the difference between “operational” aircraft and those “in reserve” when it comes to US carrier complements (a very fluid and evolutionary figure in itself).

- Armour did offer a remedy. This was demonstrated in the armoured carriers all remaining operational after kamikaze hits sustained off Sakishima Gunto.

Wartime exploits in the Mediterranean have given a false impression that the armored carriers were intended specifically for that narrow-seas setting, but Britain had worldwide commitments.

How does this make their design less relevant?

You design for the toughest possible conditions a ship will face... and for the RN that was the confines of the English Channel, Mediterranean, the Arctic and South China Sea. The threat here was torpedo boats, destroyers and cruisers - as well as land-based bombers. These did not pose such a risk in the Pacific.

- The RN had worldwide commitments. But it also had priorities. The closer Mediterranean was of greater value to the UK than the distant Pacific (Just ask any Australian about what happened after Singapore).

HMS Ark Royal during the 1930s.

The Admiralty’s eyes, roving over the vastness of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, never myopically fixed on a European land-based air threat.

Fleet projections in the mid-1930’s revealed the true priorities, calling for the deployment of eight fleet carriers - five of them to the East. The narrow European seas, often touted as the reason for the armored box, exerted minimal influence. The Mediterranean hadn’t suddenly shrunk after Ark Royal was designed.

Incorrect. The Illustrious class design was heavily influenced by the “wake-up call” presented by the Abyssinian crisis of 1935.

All of a sudden, the earlier focus on Japan and war in the Pacific was starkly replaced by the now obvious ambitions of Italy and Germany.

This is why Ark Royal (designed in 1934) was a “one-off”: The idea of building repeats of a design optimised for the Pacific was dropped in favour of a new design optimised for narrower waterways such as those found closer to home.

- Context is king. The early 30's deployment of five fleet carriers to the east was contingent on whether Japan was being recalcitrant or not / if Germany was being recalcitrant or not / if Italy was being recalcitrant or not. It was also a doctrine focus before the Abyssinian crisis. Not after. This is all evident, even if you restrict your reading to Friedman.

- Britain, like the US, would not have designed one class of ship to operate solely in the North Sea, Channel and Mediterranean and another class to operate specifically in the Pacific. They would design a ship to handle all anticipated circumstances as best they could... which involves compromise and orders of importance.

- I'm not sure what the "suddenly shrunk"; line actually means. The Med is full of choke-points and islands which offer land-based aircraft great range over its waters. What changed after Ark Royal is that Britain now believed there was a greater chance of having to fight under these conditions. And, in many ways, the Med did "suddenly shrink" in the late 1930s under the expanding capabilities (speed, range and bomb load) of land-based bomber aircraft.

design studies revealed that small carriers would prove cost-ineffective and operationally inferior; yet small air groups had an allure in placing few FAA eggs in any one basket, however large the basket might be. While no one dared apply such logic to battleships—arguing for only two or three guns per ship - it had some validity as applied to carriers in view of the limited FAA resources at the time.

A fallacious argument.

Worth does not take into account Britain’s strategic necessities: An empire reaching into every major ocean. This is why the “light fleet” trade protection carrier concept persisted through the 1930s, eventually to emerge in 1945 with the arrival of the likes of Colossus and Centaur. The operational success of this class of ship is the subject of a separate debate.

US tactical thinking developed during the 1930s tended to favour the concept of many smaller hulls as a means of counteracting the "he who strikes first wins" tendency in fleet carrier-versus-carrier wargames. Fortunately for the US, this was never enacted.

Yes, pre-war and early war FAA numbers were low – as reflected by the air groups in the ships at sea. There were plans to expand it significantly, however. But a war which unexpectedly placed Britain’s Home Islands directly under the bombs of the Luftwaffe dramatically curtailed this.

The war expansion of the FAA was seriously affected by the emergency fighter program initiated during the Battle of Britain where all construction efforts were focused on a handful of fighters and one or two bombers to defend the home island. This affected FAA aircraft production, design and development - not to mention the availability of pilots, engines and other spare parts. This could not have been predicted in the 1930s when Illustrious was designed.

The RAF mantra that “the bomber will always get through” certainly played a role. Given the contrasting “needs” for a small air group aboard a large carrier, the option to devote a hefty tonnage to protecting the air group seems an obvious one

The value of the single-seat fighter was being questioned by all three of the major carrier operating nations during the 1930s. That the F3F was still the US Navy's primary fighter in 1940 is a symptom of this. The ever increasing speed of bombers produced far less time for fighters to launch or be directed to intercept positions after visual contact was made.

At one point, Britain toyed with abandoning the concept of naval fighter: Instead, the Skua was supposed to be a dive bomber with a secondary role as fighter (an early F-35!) This was quickly seen to have been a mistake, and the emergency program that produced the Fulmar fleet fighter was initiated.

Nevertheless, it was not until the likes of Ark Royal started experimenting with radar guided fighter direction techniques (using HMS Sheffield’s radar data transmitted via semaphore and flag) in early 1940 that it became obvious – even to non-combatants the United States and Japan – that carrier based fighters were to have such a central role.

As things turned out, the Mediterranean Campaign failed to fulfill its billing as the quintessential narrow-sea setting complete with a high incidence of bomb hits.

Err, what? How can Worth possibly justify this statement with even a whit of knowledge about the war in the Mediterranean?

Well… perhaps if you only look at what happened to the armoured aircraft carriers in isolation. But that is ludicrous.

The Mediterranean more than fully lived up to its billing as a quintessential narrow-sea setting with a high incidence of bomb hits. However, it was the effectiveness of the radar-guided CAP provided by the FAA that generally reduced its impact when it came to formations covered by an armoured (or otherwise) carrier.

As evidence to the bomb-heavy nature of the sea war in the Mediterranean, read up on:

Malta convoys (all of them, not just Pedestal)

Evacuations of Greece and Crete

Supply runs to Tobruk

And that’s just for a start.

During the entire war, only fifteen bombs scored hits on Allied carriers in the Mediterranean, a number surpassed in the first year of the fight against Japan.

Again, a case of the lies, damned lies and statistics alluded to by Slade...

Not to mention, this statement runs counter to most of the assertions presented so far by Worth:

More bombers got through in the Pacific?

They were able to deliver more bombs?

Despite the extra emphasis on airgroups?

How did the carriers cope with the damage?

- The art of practical air warfare, and naval warfare for that matter, underwent a severe reality check after September 1939. Many old ideas went out the window through the harsh reality of experience. But it took time for this to be realised by the combatants, Non combatants such as the US and Japan were able to watch and learn.

- All carriers in the Med (armoured or not) faced high-level and shallow-dive bombing attacks virtually every time they went to sea. That there was so few hits reflects on the tactics of the attackers, the effectiveness of the anti-aircraft barrages in disrupting bomber formations, and the determination of the limited FAA pilots in doing the same.

- These 15 bomb hits were delivered in just three actions, two against solo carriers. This is despite the carriers being subjected to dozens of air attacks.

- While there may have been only 15 direct hits, all carriers (armoured or not) suffered many more “near misses” which contributed to the accumulation of underwater structural damage.

- Many of these 15 hits were by weights at least double, up to quadruple, the weight of those bombs usually encountered in the Pacific.

- These bombs were usually delivered from close to optimal ballistic heights by trained pilots in contemporary machines, not by poorly trained and equipped kamikaze pilots.

Of the fifteen hits, the Illustrious class flight deck armor defeated only one – Victorious shrugged off an anti-personnel bomb dropped at low altitude by an Re.2001 fighter.

Correct - almost. The Illustrious class flight deck armour was hit three times in the Med. Two were deflected.

Hit one: 2200lb bomb almost on the centreline on the main armored “box” of HMS Illustrious.

Hits two and three: Two bombs of indeterminate size dropped by the Re2001 fighters on to HMS Victorious. There are conflicting reports as to what these bombs were. Some accounts state they were experimental low-altitude anti-armour weapons. Others state they were anti-personnel bombs. My reading indicates it was supposed to be the experimental weapons, but they were not ready at the time of the attack so anti-personnel bombs were used instead. Either way, probably due to their low-altitude release, one broke up on impact when striking the armoured portion of the deck. The other bounced over the side.

Indomitable's demolished rear flight deck after Operation Pedestal. The Spitfires on the deck were to be flown off before the carrier returned to the UK.

Indomitable took two 500-kg hits, but both of them avoided her armor which thus did nothing to preserve her flight deck; the ship was non-operational for the remainder of the action.

Sort of correct. But the bomb weight is wrong. The damage assessment reports determined the bombs to be 250kg (550lb) “burster” types.

And there is much more to the story.

Again, the point of difference is the effect of the 250kg (550lb) HE bombs that hit and near-missed her, against that of the 250kg (550lb) bombs which induced such terribly higher death tolls - and destroyed the hangars - aboard the carriers of other nations under similar circumstances.

Put simply, the blast and fire from these hits in the bow and stern were prevented from causing a conflagration in the hangar by the armoured box.

It is interesting to note that David Hobbs in his book British Aircraft Carriers (though he was correct in his reporting of Illustrious's 2200lbs (1000kg) penetrating hit) incorrectly states Indomitable "was hit by two armour-piercing bombs which defeated and penetrated the flight-deck armour".

Indomitable's Admiralty Damage Report (found on the Home page here) shows the aft bomb hit behind the aft lift in the light flight deck plating, while the forward hit may have - at best - penetrated the "1.5in equivalent" structural steel plate surrounding the lift well.

Both were assessed to be 250kg (550lb) bombs.

Of the two 500-kg bombs dropped on Formidable, one struck her deck armor and sent pieces of it shooting all the way down into the ship’s machinery spaces.

Worth once again gets the bomb weights wrong.

He has clearly not read any further than Friedman.

Regrettably, he’s not the only one.

In what looks to have been an unfortunate error introduced by editing in Norman Friedman’s excellent “British Carrier Aviation”, the battle damage sustained by HMS Formidable in two separate actions – off Crete and Sakishima Gunto– have been conflated into one.

- Formidable was hit by two 550lb (250kg) bombs carried in two kamikaze attacks in 1945. Both detonated on the armoured flight deck. The first explosion caused the junction of three flight deck armour plates to spall, a splinter of which penetrated through the engine room. She was back up to full speed in about 12 hours. The second was entirely defeated by the armour.

- In the Mediterranean, while off Crete in 1941, Formidable was hit by two 2200lb (1000kg) bombs. One was on the unarmoured portion of the flight deck in front of the forward lift. The other was on the starboard 4.5in gun sponson. Formidable remained operational.

- Worth and Slade’s understanding of what actually happened is therefore confused. And little of significance should be read into the fact an armour spall was produced by a kamikaze hit. Similar armour fragmentation happened to the Essex and Yorktown classes from their armoured hangar deck.

- Indomitable resumed (limited) flight operations delivering Spitfires about three days after the attack and provided her own anti-submarine cover upon her return to the UK. She was never in danger of sinking. Her casualties were low compared to other carrier incidents.

- Formidable landed two aircraft 5 minutes after being hit in the Mediterranean in 1941 and re-started flying off CAP about three hours later. This further degrades Worth’s argument.

So the armored box’s primary achievement in this narrow-sea setting was to detonate the two Formidable and Illustrious bombs high in the hull, which certainly enhanced survivability, though not in the way the designers intended.

Worth introduces another error of fact. The bombs penetrated the strengthened and light steel components of the flight decks of Formidable and Indomitable, not the 3in armoured "box” above and around the hangar.

And he fails to recognise their armoured hangars isolated volatile aircraft, fuel and munitions from the splinter damage and fires these hits caused.

- This "box" was based on the principle of treating the hangar like an ammunition magazine. It acted exactly the way the designers intended.

- Designers intended the damage of a heavy bomb which penetrated the hangar space (such as the 2200lb weapon which struck Illustrious) to be contained by blast doors and airlocks, as well as the armoured box. This succeeded in reducing damage to Illustrious' vitals.

The increased extent of damage to the volatile hangar by deck hits on unarmoured carriers is demonstrated by this image of USS Franlkin.

The hangars and their planes suffered increased damage, but crippling damage to the vitals became less likely.

Wrong.

Worth offers no substantiation for this assertion as there is none.

The aircraft in the armoured carriers' hangars were largely untouched by the blast or fires from any attack in the Med or Pacific.

- In three instances, a small amount of burning fuel spilled into the hangars (through the fracture in Formidable’s armoured plate joints, a popped rivet in Formidable's next attack and a torpedo lift on Indefatigable). In no instance did this produce a serious threat to the hangar or the ship.

- Many aircraft would be marked as "written off" due to the threat of corrosion damage when drenched by the salt-water hangar fire sprayers. But many of these would be restored to service by the home ship, or sent back to HMS Unicorn as "flyable duds" for restoration.

- Illustrious’s hangar was extensively damaged in January 1941. But this was from a direct hit from a 2200lbs weapon, and three bombs (a mix of 1100lb and 550lb weapons and possibly a crashing Ju87) which detonated inside the aft lift well. Nevertheless, several aircraft (Swordfish) were judged to have survived in a "restorable" condition. The armoured and flash-tight hangar reduced the spread of these fires, as well as limited the impact of bomb splinters and 'cooking-off' ammunition.

- In Formidable and Indomitable's Mediterranean ordeals, the box hangars prevented external damage and fires from reaching the hangars.

It is therefore utterly incredulous to say the armoured carriers' hangars suffered "increased damage" because of their design.

There’s no debating the advantage of this; yet debate continues, and properly so, because of the extra ounce of prevention the ships could have enjoyed with a larger CAP. Accepting a small fighter group meant accepting a greater probability of bomb hits, with the hopes of minimizing the damage those bombs caused - a strange set of priorities.

As previously conceded, this is an interesting and valid point. And one Worth contradics himself with when he points out US carriers sustained more hits in 1942 than British carriers had in 1939-41:

- Yes, Yorktown had 20 Wildcats in the air (12 on CAP, 8 intercept launches) at Midway. These didn’t save her from the carrier-launched dive-bombing attack.

- Even the combined strength of USN fighters from three Task Groups didn’t always prevent kamikaze attacks “breaking through” to US fleet and amphibious units off Okinawa.

- Successful kamikaze attacks on US carriers generally caused “mission kills”, where the carriers had to withdraw for repair – at best to Ulithi for a few weeks, at worst to Pearl or the US mainland for several months.