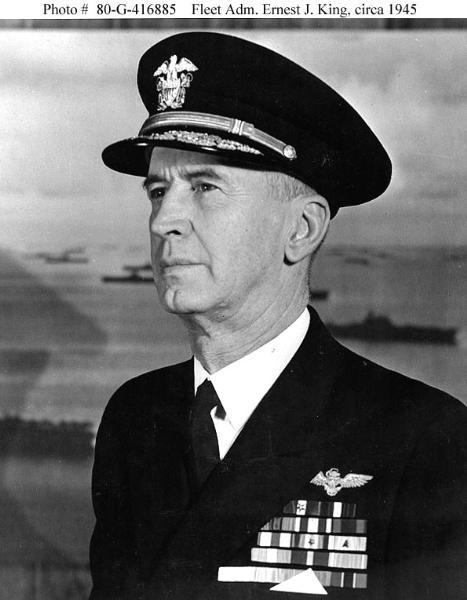

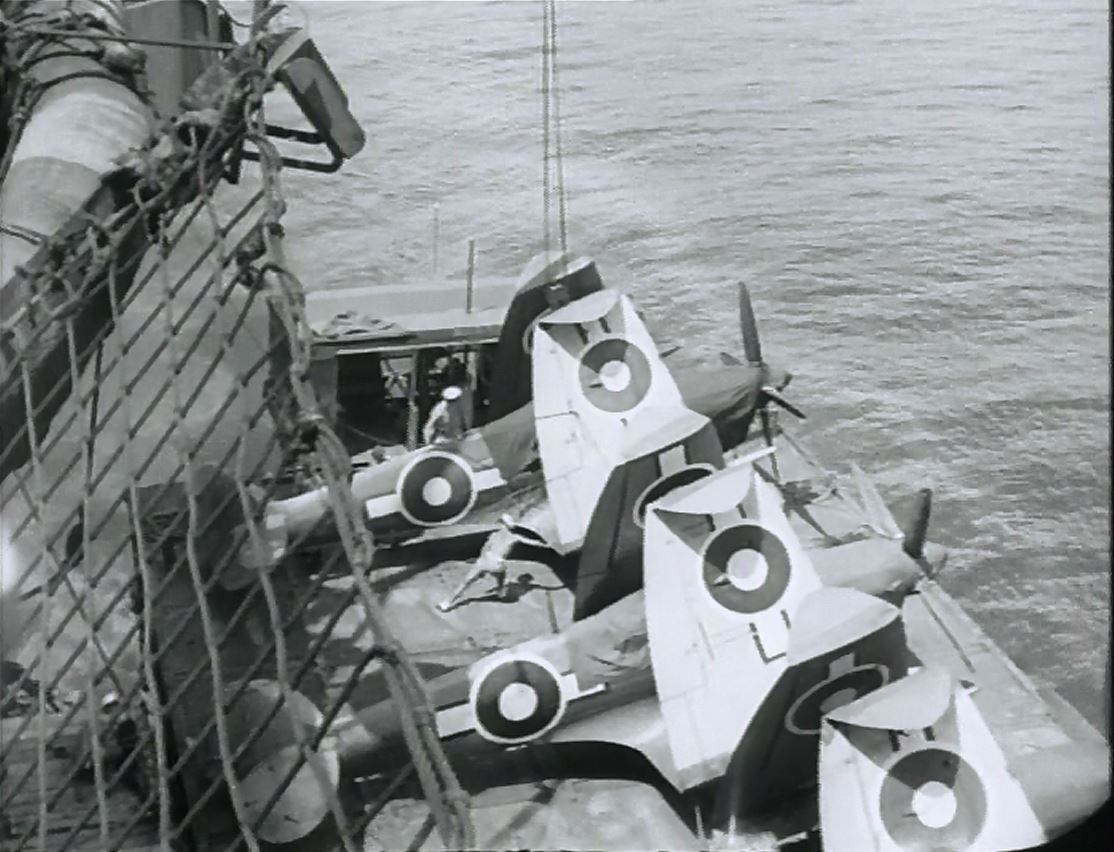

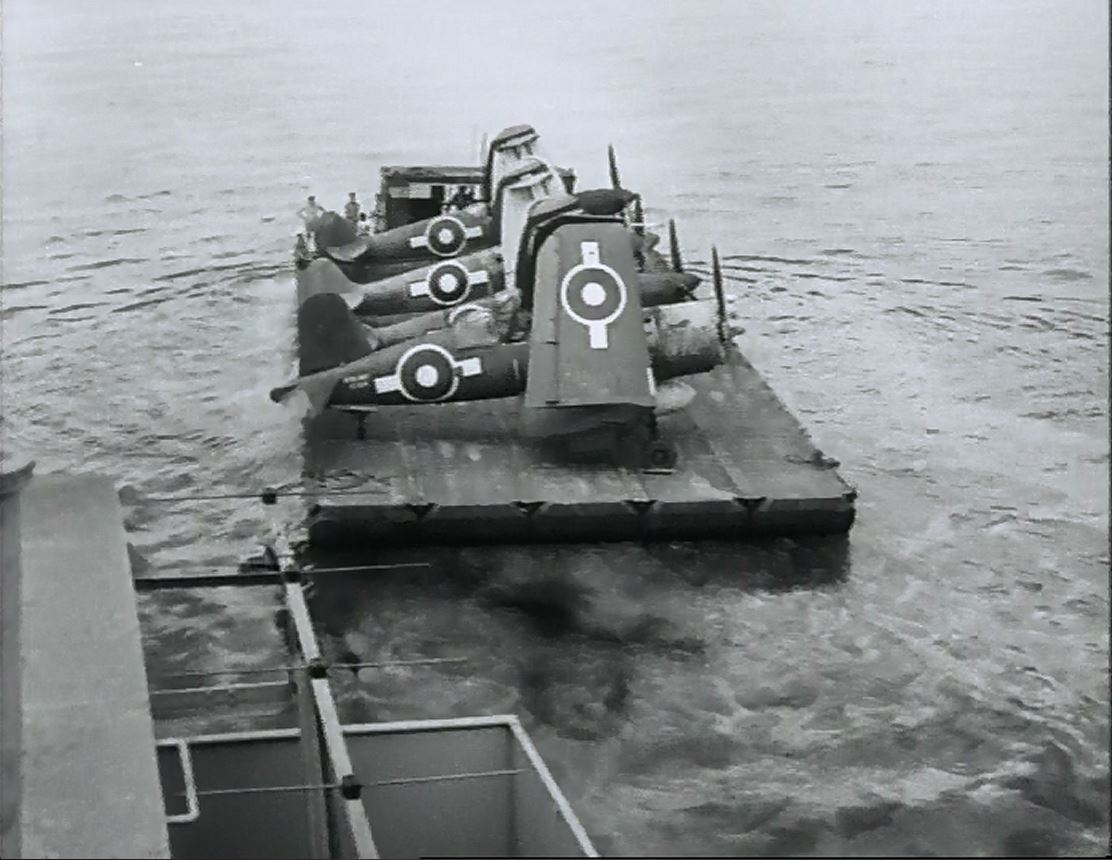

A Seafire is slung over the side of what may be HMS UNICORN before being positioned aboard a lighter for transfer in Leyte Harbour.

During ICEBERG I, Task Force 57 matched US operational practices by staying at sea continuously for 32 days. The formation had been in in action for 12 out of the 26 days spent in the combat zone. Some 2444 aircraft sorties had been flown, 1961 by fighters and 483 by the Avengers.

Bombs totalling 412 tons had been dropped and 315 rockets were fired by the Fireflies.

The fighters contributed 44 tons of bombs to the effort. Hellcats would often carry a single 500lb bomb while the Corsair would carry two.

The British Pacific Fleet rued that it had not been equipped with fragmentation bombs with air-burst fuses. This reduced the FAA’s capacity to neutralise enemy gun positions. The traditional “iron” bombs used tended to have their blast effect reduced by mud.

The battleship HMS King George V had fired 119 rounds of 5.25in ammunition, 1930 of 2pndr pompom, 118 of 40mm bofors and 2183 of 20mm ammunition. Howe’s figures were similar.

A total of 134 Japanese aircraft were claimed destroyed or damaged: Included were 33 shot down and 12 wrecked while on the ground. Some 100 coastal vessels were also damaged or destroyed.

The Sakishima airfields had been denied to the enemy, forcing them to adopt a much longer route from Formosa to the Okinawa battlefield. It also denied returning Japanese aircraft a safe refuge.

The diversion to Formosa, ICEBERG OOLYONG, proved to be Task Force 57’s most successful interdiction operation. The target airfields and their infrastructure were damaged, road and rail networks hit. In combat, some 16 enemy aircraft were shot down for the loss of only three FAA machines.

Overall during ICEBERG ONE the task force had lost 19 aircraft to flak and another 28 to a variety of operational causes. Sixteen pilots and 13 aircrew had been killed. This represented a casualty rate of 28 per cent.

Corsair and Hellcat pilots flew an average of 45 hours each during ICEBERG I. Seafire pilots flew about 22 hours, and Avengers 15.

Admiral Vian assessed his aircraft, carriers and equipment as barely adequate for the task. But he recognised how much had been achieved under a steep learning curve.

He wrote in Action This Day:

“As targets, the airfields proved to be both disappointing and dangerous. Though heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns, few seemed to be in active use. Furthermore, the runways, being hewn out of coral, were easily repaired during darkness, when operations ceased. As a result, not only was it necessary to repeat attacks day after day, but a large proportion of our effort had to be diverted to attempts to put the anti-aircraft defences out of action. In this we were not altogether successful, the high-explosive bombs with which our aircraft were armed not being very effective against such targets."

Vian's most urgent request, however, was for a fully equipped night-flying carrier to maintain strikes on enemy airfields “around the clock”. HMS Ocean, still in Britain, was being fitted-out to fill this role. Many pilots bemoaned the absence of the stoic “Stringbag”, the Fairey Swordfish. This obsolecent biplane would have at least allowed them to conduct harassment bombing raids at night.

The suitability of CAP procedure during ICEBERG I was also believed to have been inadequate. Having 12 fighters spaced between high, medium and low CAP positions had proved insufficient to fully respond to the raids encountered.

While the Seafire was capable of handling the difficult low-level interceptions, the high-flying enemy formations tended to break up before the Hellcats and Corsairs reached them – making their way individually in attack runs on the fleet.

It was intended to boost this CAP to 20 aircraft where possible for ICEBERG II.

HMS VICTORIOUS at Leyte.

USN Liaison Officers

Several experienced USN officers were embarked with the BPF during ICEBERG I. They were there to share their knowledge of Pacific conditions and operations, as well as to observe the British way of doing things.

Initial impressions seemed to be poor.

HMS Indomitable’s USN fighter direction liaison officer – while very impressed with the skill of the fighter direction teams – was unhappy with the standard of accommodation. He felt the lack of “necessities, conveniences and comforts” in the British carriers – which were not designed to operate in such heat - was leading to the early onset of battle fatigue.

The senior liaison officer was Captain E C Ewen, previously captain of the night-operations light-fleet carrier USS Independence. He was assigned to work with Rear Admiral Vian aboard HMS Indomitable.

His first impressions of the British carrier were not positive. He judged that the design of the flight deck limited the number of aircraft in each launch “range” to only 25, and that handling parties were barely up to the task.

Ewen regarded the launch rate to be good, but was critical of the time taken between each aircraft landing. His argument that the FAA should adopt the USN’s “straight on” landing approach did not take into consideration the unique challenge the British force faced – such as smaller decks and weaker landing gear.

Ewen reported to his superiors that the catapult – raised above the armoured deck – would sometimes interfere with drop tanks and was thus not often used. He also noted that the steel decks, unlike the US wood decks, could become dangerously slippery with oil and water – particularly when it rained.

He was also critical of the number of men in the maintenance teams, noting that it would restrict operational flying through the reduced repair and deep maintenance capacity.

The “turn-around” time of FAA aircraft between strikes left a lot to be desired, he reported, citing one instance where 16 Hellcats took 2.5 hours to rearm and refuel.

Ewen also did not hide his dislike for Vice Admiral Vian. He was not alone. Many found the fractious former destroyer flotilla leader - who had won fame through seizing the prison ship Altmark - difficult to deal with.

On the other side of the argument, Vice Admiral Vian pointed to a dispute which he says set Ewen against him.

Vian had been especially keen on ensuring the best possible efforts were made to rescue his downed aircrew. In one instance, an Avenger crew was seen to ditch safely in the water and deploy its dinghy just outside the lifeguard submarine zone. Vian asked Ewen to send the submarine to the rescue after briefing all pilots in the area as to what was happening.

Vian later wrote:

“This he refused to do. Being desperate, since the sea was too rough to operate our own rescue aircraft, I appealed, through Admiral Rawlings, to Admiral Spruance. The Admiral readily agreed and the crew were duly saved but the Liaison Officer never forgave me.”

Captain Ewen was moved to HMS King George V on April 5, where he joined USN’s Captain C Julian Wheeler, previously a cruiser captain, on Admiral Rawlings’ staff.

Ewen found Admiral Rawlings much more to his liking.

By the time Captain Ewen left the British Pacific Fleet upon its arrival in Leyte, his opinions of the armoured carriers had significantly improved to the point of being generally impressed.

He particularly noted how the British carriers had shrugged-off kamikaze hits that would have put US carriers out of action. He reserved the highest praise for the commander of HMS Victorious, Captain Denny, whom he said handled his ship in a particularly skillful manner. He also admired the detail and clarity of Captain Denny’s reports, which he recommended as a template for all other carrier commanders.

HMS FORMIDABLE is in the foreground of this picture of BPF carriers and cruisers anchored at Leyte.

King’s Move: Checkmate in One

Admiral Rawlings went to visit Admiral Kinkaid, Commander of the US Seventh Fleet, immediately upon the arrival of the British Pacific Fleet at Leyte.

Here he learned that the future of Task Force 57 was once again up in the air. Admiral King had asserted he would invoke his seven-day notice clause and send Task Force 57 with the Seventh Fleet to cover Australian troops operating in Borneo in the South-West Pacific. He wanted them to be on their way by May 15 to support the almost pointless landings at Tarakan.

All that Admiral King needed was the consent of Admirals Spruance and Nimitz.

He did not get it.

Instead, they lobbied Admiral Kinkaid and General MacArthur hard to call for the continued presence of the British fleet off Japan.

Admiral Nimitz, in particular, had by now recognised the strength of the British carriers’ armoured flight decks. They were far less vulnerable to kamikaze attacks than his own wooden-decked assault carriers which had suffered unexpectedly high attrition, he said. The British ships would thus be needed as the war moved closer to the Japanese homeland.

Nimitz and Spruance knew the kamikaze attacks always seemed to get enough aircraft through the fleet’s defences to damage vital capital ships. And their number and intensity was expected to only increase in coming months.

On April 27, Admiral King reluctantly relented. He signaled that the diversion to Borneo had been cancelled and that TF57 should remain part of the Fifth Fleet.

Even though King’s long-distance meddling from Washington was overturned, Admiral Fraser – from his Sydney office – was left wondering just who was actually in command of US forces in the Pacific. The lack of a “Supreme Commander” had created a “chaotic and nearly calamitous state of affairs”, he would write.

Admiral King’s autobiography of 1953 asserted his opposition towards the British Pacific Fleet had nothing to do with any ill-will on his behalf, but rather his fear of the Royal Navy’s lack of logistical support. He doubted the capabilities of the Fleet Train due to its rag-tag nature and lack of experience.

He would say in Fleet Admiral King – A Naval Record:

HMS UNICORN, a floating aircraft repair and maintenance factory, on station in Leyte.

“The most desirable solution would be for the British Pacific Fleet to be assigned certain tasks in the Pacific to carry out independently, rather than for ships of the Royal Navy and the United States Navy to be maneuvered together.”

But Admiral King could never bring himself to even name Admiral Fraser once in his book. He was simply designated “the officer”:

“The officer would report to King, who would in turn give him specific directions.”

Task Force 57 is mentioned only three times, and completely ignored in relation to the Okinawa operations.

Leyte Layover

A Seafire is hoisted aboard one of the BPF's replenishment / escort carriers.

The replenishment and repair period at Leyte proved more comfortable than Task Force 57’s previous experience at Manus.

The weather was more mild and the waters calmer.

There was no shore leave: Every boat was needed in the desperate race to shuffle supplies between the 60 ships of the Fleet Train and the warships before their next deployment.

Tired crews were dismayed to discover that the delay caused by the extra days off Sakishima Gunto had caused much of the perishable food to spoil before it could be distributed among the warships.

In a token effort to alleviate the strain, Admiral Rawlings ordered beer be brought from ashore and distributed among the crews at the rate of one can per man per day.

This “liberty” was well received: The carriers went so far as to set up “beer gardens” on their flight decks so weary crew could relax in the cooler evening air with a “coldie” in hand.

Repair and supply ships are anchored ahead and around the fleet carriers of the British Pacific Fleet. HMS ILLUSTRIOUS (center) is in a row separate from the other carriers as she is being offloaded of useful components before returning to the UK for extended refit and repair.

Repair and replenishment

The repair ships HMS Resource and Artifex were put to work restoring the Indefatigable’s damaged flight deck equipment and island to full flight operations status within only six days.

The heavy repair ships were equipped with foundries, smiths, plumber and carpentry workshops. Electrical repair and maintenance offices were particularly hard pressed.

The destroyer depot ship HMS Tyne was equipped with two furnaces capable of shaping, pressing and moulding up to 500lb of steel – along with a variety of heavy machinery for complex repairs and maintenance.

Maintenance crews aboard HMS Unicorn and the engine repair ship Deer Sound were to work around the clock preparing new aircraft and restoring “flyable duds” to service so that the carrier squadrons could have a full complement. Unicorn's 10 aircraft-carrying lighters were particularly hard-pressed in a fleet facility desperately short of small boats to transfer equipment and supplies between the ships.

A Hellcat is moved aboard a lighter at Leyte.

The damaged destroyer, HMS Ulster, had already been quietly taken in hand by US repair facilities in Leyte: The US commanders in the field had proven good to their word.

Work boats were sent to and fro between every warship and VSIS (Victualling and Stores Issuing Ship) with long shopping lists for provisions and spare parts. This would not have been possible without the USN allowing the British to use spare landing craft and harbour vessels.

The VSI ships of the Fleet train were fitted specifically for purpose. They were not bulk-load ships like most merchant vessels. Instead, they carried their 2500ton loads like giant department stores. Cargos were catalogued and stowed so that victualling officers could access whatever was needed immediately.

A spare Avenger is moved between ships at Leyte.

Rounding out the Feet Train were Ammunition Stores Issuing Ships (ASIS) and Air Store Ships.

Crews, while allowed no leave, at least had a break from routine: Many found themselves working long hours in the human chains lugging and stowing an endless stream of supplies, ammunition and equipment.

HMS Illustrious had arrived ahead of the main body after being relieved by HMS Formidable. She still sat in harbor, having her damaged hull looked at. It had proven more severe than first thought, with a significant area depressed by concussion and several plates and frames cracked. After distributing her spares and stores among the other four carriers, she was sent on the long journey home for a much delayed major refit. Nevertheless, it was a scheduled departure: HMS Formidable's late arrival had finally freed Illustrious from extended duty for her long-overdue overhaul.

As usual, a tanker group of the Logistics Service had gone on ahead to refuel the cruisers destroyers at Service Area “Mosquito One” once they arrived on May 3. This group of some 12 vessels was escorted by a force of three anti-aircraft sloops, four RAN “N” class destroyers, three “W” class destroyers and three “River” class anti-submarine frigates. The escort leader was the sloop HMS Pheasant and CAP was provided by the escort carrier HMS Ruler.

Task Force 57 left San Pedro Bay at 0630 on May 1 and pointed its bows towards Sakishima Gunto. In the words of Rear-Admiral Vian, the fleet was “rested, if not refreshed”.

HMS Illustrious would leave for Sydney on May 4 along with the anti-aircraft cruiser Argonaut and the destroyers Wager and Whelp – all of which were also overdue for extensive overhauls.

ICEBERG II Order of Battle

1st Battle Squadron: HMS King George V (Flag TF57), HMS Howe

1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron: HMS Indomitable (Flag of 2nd in command TF57, Admiral of Carriers), HMS Victorious, HMS Formidable, HMS Indefatigable.

4th Cruiser Squadron: HMS Swiftsure (Flag of Cruiser Command), HMCS Uganda, HMNZS Gambia, HMS Euryalus, HMS Black Prince

25th Destroyer Flotilla: HMS Grenvelle (Captain D25), HMS Ursa, HMS Undine, HMS Urchin, HMS Urania, HMS Undaunted

4th Destroyer Flotilla: HMS Quilliam (Captain D4), HMAS Queenborough, HMAS Quiberon, HMAS Quickmatch, HMAS Quality

27th Destroyer Flotilla: HMS Kempenfelt (Captain D27), HMS Whirlwind, HMS Wessex