The success of a carrier cannot be separated from that of its aircraft. Such was the case with HMS Formidable in May 1941 when she found herself thrust into waters clearly under German air superiority.

Her Fulmars put up a brave fight. But, in the end, the 12 tired fighters simply did not have enough stamina to maintain the necessary level of operations.

DESPERATE times call for desperate deeds. The urgent need to stem the flow of devastating air attacks on Crete and units of the Royal Navy in the eastern Mediterranean saw HMS Formidable’s tired and depleted air wing pitted against the might of X Fliegerkorps.

The outcome may almost be seen as inevitable.

HMS Formidable’s paper air-wing strength at the time was listed as 41 aircraft:

• 12 Fulmars (803 squadron

• Up to 8 Fulmars (806 squadron)

• 12 Albacores (826 squadron)

• 9 Albacores and Swordfish (829 squadron)

But, by March 1941, the cost of emergency measures put in place during the Battle of Britain had struck home. All Fleet Air Arm aircraft production had been suspended to contribute to a “total effort” in the supply of Hurricanes and Spitfires for the defence of the home islands.

Bomb damage to the Fleet Air Arm's main aircraft supplies equipment depot made circumstances all the more difficult.

By the time of Formidable’s arrival in the Mediterranean early in 1941, FAA stocks of reserve aircraft and components were being rapidly depleted.

It was a constant struggle to maintain an adequate number of operational aircraft.

A detachment from Illustrious’ 805 Squadron (Fulmars) is listed as being embarked between March and April 1941 and increasing numbers of Swordfish were being drafted to maintain an effective TBR (torpedo, bomber, reconnaissance) wing as replacement stocks for the newer Albacore were scarce.

Operation MAQ3 appeared doomed from the start.

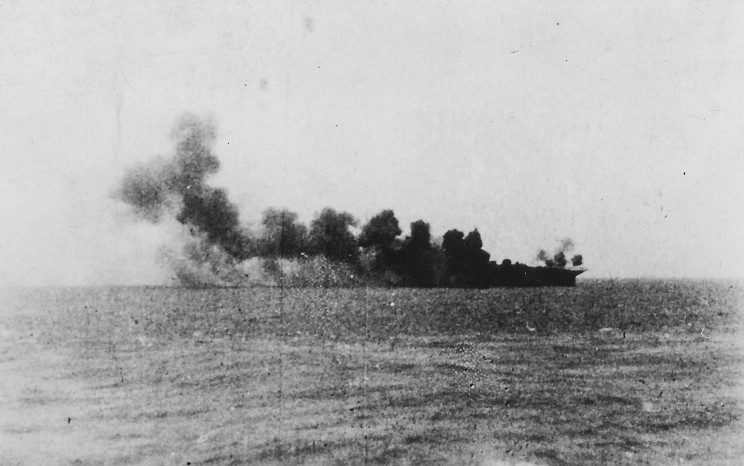

The damage to HMS Formidable was spectacular, but less extensive than that suffered by HMS Illustrious earlier that year.

It took six months and a US dockyard before the carrier could return to service.

NOTE: The title is incorrectly dated. This footage appears to be of Fulmar and Albacore flight operations aboard HMS FORMIDABLE in 1941.

Prelude

On May 20, HMS Formidable – when the protection offered by her Fulmars was needed the most – found herself tied up in Alexandria.

She had only a handful of serviceable fighters.

The attrition of the previous three months of near constant action had simply been too high, and the flow of replacement aircraft too slow.

A desperate hunt was underway for aircraft, spare parts and equipment.

German forces were marching down the coast of Greece and the first attacks on Crete had begun.

The last RAF aircraft on Crete had been withdrawn to the safety of Egypt on May 19: The numbers of German fighters were simply overwhelming and further air operations were considered wasteful.

But the Royal Navy still strove to maintain control of the seaward approaches to Crete and its beleaguered defenders.

Fully aware of the risks, the sailors at least had learned the lessons of Norway, the warships pressed on in the face of an enemy in complete control of the skies.

A significant victory was achieved on May 21 when three cruisers and four destroyers intercepted and sank 11 small vessels carrying troops. Some 297 German soldiers and sailors were killed.

Retaliation was swift: Luftwaffe attacks damaged HMS Dido, Orion, Ajax and four destroyers in four hours of sustained bombing.

Italian aircraft sank the destroyer HMS Juno south-east of Crete.

The next day was a disaster: HMS Naiad and Calcutta were damaged in air attacks. HMS Warspite was so severely damaged (with 43 killed and 69 wounded) she was later ordered to the United States for extensive repairs. The cruisers HMS Gloucester and Fiji were left exposed, having used all their anti-aircraft ammunition, and swiftly sunk by Stukas.

On May 23, HMS Kelly and Kashmir were sunk by 20 Ju-87s from I/StG2 after the ships bombarded German bridgehead positions at Maleme airfield, Crete.

Something simply had to be done about the Stukas.

Message from Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, to Admiralty

[CAB 121/ 537] 1049,

3 May 1941

Operations around Crete without air coverThe operations of last 4 days have been nothing short of a trial of strength between Mediterranean Fleet and German Air Force.

The immobilisation of carrier owing to fact that only 5 serviceable fighters could be produced coupled with inability of R.A.F. to provide any fighters at all since no aerodromes could be used in Crete meant that we had no air assistance at all other than a relatively small scale bombing attack on the aerodrome.

I am afraid that in coastal area we have to admit defeat and accept the fact that losses are too great to justify us in trying to prevent seaborne attacks on Crete. This is a melancholy conclusion but it must be faced.

As I have always feared enemy command of air unchallenged by our own Air Force and in these restricted waters with Mediterranean weather is too great odds for us to take on except by seizing opportunities surprise and using utmost circumspection.

I am discussing the matter today with Deputy C. in C., Middle East and A.O.C. in C., Middle East regarding our next moves particularly as regards Crete.

In the meantime, I have withdrawn all forces to reammunition and refuel. It is perhaps fortunate that H.M.S. FORMIDABLE was immobilised as I doubt if she would now be afloat.

Admiralty pressure

It is against this backdrop of overwhelming air attack that Admiral Cunningham had to contend with “most unhelpful” instructions from the Admiralty Office in London.

The Commander-in Chief had informed the Admiralty that the scale of air attack now made it impossible for his ships to operate in the Aegean or near Crete in daylight.

The admiral wrote:

“The Navy could not guarantee to prevent seaborne landings without suffering losses, which, added to those already sustained, would very seriously prejudice our command of the Eastern Mediterranean.”

The Admiralty retorted that only experience would determine how long operations could be maintained.

The Chiefs of Staff reply was blunt: If greater effort than that suggested by Cunningham was not enacted, the enemy would be able to considerably reinforce their invasion force upon Crete.

The Fleet and Royal Air Force must “accept whatever risk” in preventing reinforcements reaching Crete, and considerable losses were expected.

May 25, Operation MAQ3

In a move hinting at desperation and bowing to political pressure, Commander-in-Chief Admiral Cunningham ordered HMS Formidable to put to sea with his battle fleet.

Intelligence had assessed that most of the damaging Stuka attacks were being launched from Scarpanto (now known as Karpathos) in the Dodecanese Islands, some 50 miles east of Crete. HMS Formidable’s aircraft were to attack the airfield.

In a marathon effort, Formidable had been able to restore its air group to a total of 27 aircraft. A narrative dated 24 May, 1948, by Admiral Cunningham reports the carrier had 12 operational Fulmars (though some he regarded as “suspect”).

Captian A.W. Bisset’s Proceedings Report adds that Formidable sailed with a reduced complement of seven Albacores and eight Swordfish. There were 13 Fulmars aboard, though one was already unserviceable after a deck-landing accident.

Nevertheless, the number was considered adequate to protect the carrier, the fleet, and conduct a strike.

At noon on May 25, Force A departed Alexandria for Scarpanto Island for operation M.A.Q.3.

Royal Navy Order of Battle

Force A:

Carrier: HMS Formidable (Flagship Rear Admiral (Air) D. W. Boyd)

Battle Squadron: HMS Queen Elizabeth, Barham.

Destroyer Squadron: HMS Jervis, Janus, Kandahar, Nubian, Hasty, Hereward, HMAS Voyager and Vendetta.

A Luftwaffe airman sits resting against a 1000kg (2200lb) bomb while stationed at an airfield in the Crete theatre.

Axis Order of Battle

Ju88s of LG1:

III/StG2, X Fliegerkorps: Scarpanto:

II/StG 2, X Fliegerkorps: This elite Stuka unit appears to have been temporarily based out of Tmimi, North Africa. The unit seems to have only recently relocated, having spent much of the time since the Illustrious Blitz against Malta at the nearby base at Derna.

The back-and-forth campaign against the British in North Africa was entering another “forwards” phase for the Germans.

Tobruk was heavily besieged, relying on daring runs by destroyers and fast merchant vessels to maintain the supply of food and ammunition.

The Stukas of II/StG 2 were an ideal choice for interdicting this supply route. And this was their intention when they took to the air on May 26.

Scarpanto Strike

By 0300 on May 26 the fleet had made its way to about 100 miles south-south-west of Scarpanto. A force of 12 aircraft was ranged on deck for the strike.

Things did not go well. Seven Albacores were prepared for the dawn attack. Each carried a load of 4x 250lb GP bombs and 12x 40lb bomblets. Six Fulmars were to join the strike as escort and to strafe the airfield.

Admiral Cunningham’s report states:

“Of four other aircraft intended to take, part in the attack, two could not be flown off and two returned to the carrier owing to unserviceability.”

One of the Albacores failed to start after it had been hauled up to the deck. But the remaining six flew off at 0330.

One returned 30 minutes later to make an emergency landing with engine trouble. Its wingman subsequently lost touch with the main formation and, after a fruitless effort trying to find it, also returned to the carrier at 0509.

The Albacore strike was reduced to just four machines.

Six Fulmars had been ranged for take-off at 0430 after the Albacores had departed. Their mission was to make strafing runs as the Albacores attacked.

But their launch was delayed by the Albacore’s emergency landing. Once the deck had been cleared and reorganised by 0500, only four Fulmars departed - 30 minutes late. Two had developed faulty engines while warming-up and had been struck below.

The four remaining Albacores attacked Scarpanto between 0505 and 0515, dropping their bombs in the dark. A few RAF Wellingtons had timed their arrival to participate in the attack.

The Fulmars made their strafing runs at 0545 and reported seeing at least two destroyed aircraft on the ground. Observers counted 15 Ju87s and 15 CR42s arrayed in lines on the field.

The four Albacores and four Fulmars that participated in the attack all returned safely to Formidable – the TSRs at 0625 and the fighters at 0655.

Force A then withdrew to the south.

Admiral Cunningham’s narrative states that Formidable had only eight remaining serviceable fighters at this point. These would sortie 24 times during the forenoon, engaging in 20 combats, he wrote.

Dawn patrol

While the strike Albacores and Fulmars were over Scarpanto, HMS Formidable’s radar had been tracking a considerable number of air movements in the area. Some were believed to have been the Wellingtons that had attacked Scarpanto. But others were unidentified.

As the radar contacts continued to appear after dawn, a fighter section from 806 squadron was launched at 0535 as a precautionary air patrol.

At this time Force A was about 100 miles south-west of Scarpanto, south of the Kaso Strait.

Grey Section was ordered to attempt an interception at 0640 when an unidentified echo was detected at 45 miles. This could have proven difficult: the Fulmars from the Scarpanto raid were beginning to land on the carrier. Grey Section was recalled when the contact was lost.

A second detection was made at 0700, with an echo coming from the north at 55 miles. The fighters encountered a Ju88, but the bomber’s speed was too great for an effective engagement. Captain Bisset’s “Report of Proceedings” says Grey Leader’s aircraft was received slight bullet damage in this encounter.

Also at 0700, Force A’s defences were augmented by the arrival of the cruisers HMS Ajax and Dido, along with the fleet destroyers HMS Napier, Kelvin and Jackal.

White & Black Sections

A relief patrol, White Section, was launched at 0733 and almost immediately directed towards a new contact. This Ju88 was engaged and shot down about 30 miles north of the fleet at 0750.

A third fighter patrol was launched at 0810. Designated Back Section, it was later ordered to intercept a contact 10 miles north of the fleet. They engaged at 0840. Black 2 (piloted by Jackie Sewell of 806 Squadron) claimed to have shot the He111K down. It was Sewell’s 13th victory.

As Black Section was returning it was redirected towards a new echo. At 0855 they engaged and drove off a Ju88. It was seen flying low and slow with its starboard engine stopped before it ditched.

The engagement came at a price: Black Leader, flown by 806’s Squadron Leader Garnett, was hit in the engine cooling system and was forced to ditch near the fleet.

HMS Hereward came to the rescue of both crew members at 0940. Black 2 landed on Formidable five minutes later.

Brown & Yellow Sections

Brown Section had been launched as replacement air patrol at 0903. They were directed to a contact 40 miles from the fleet which they engaged at 0944. Piloted by Lt Bob MacDonald-Hall and Sub Lt Graham Hogg, the pair of Fulmars intercepted a two Ju88s. Attacking in unison, one Ju88 was set on fire. Following it down, the Fulmars observed the bomber striking the sea.

This action made Sub Lt Hogg an ace.

Yellow Section was launched on air patrol at 0948. For a time, the feet had four Fulmars in the air.

At 1008 Yellow and Brown Sections were sent to a contact to the south-east. Both flights failed to intercept and the enemy aircraft sighted the fleet about 1015 before passing out of range to the north-west at 1030.

Another failed interception occurred after an echo was located 70 miles from the fleet at 1050. Yellow Section was directed to intercept, but failed to gain visual contact with the enemy. The aircraft circled the fleet from 1110 at a distance of 15 miles.

Grey Section

Grey Section had taken off at 1100. Fighter controllers directed the Fulmars into a favourable position by 1120. The Ju88 sighted the approaching fighters and turned to flee. The chase lasted some 10 minutes, but the Fulmars were not able to get any closer than 600 yards.

Grey Section aborted the chase at 1135, and the Ju88 turned back shortly afterwards.

Grey 2, which had become detached during the initial interception, was sent after the bomber at 1200. Once again, the Ju88 proved too fast for an effective attack.

Force A altered course once again. This time it turned west to provide distant cover for a convoy – a convoy the Germans determined to attack.

Grey & Red Sections

Red Section’s Fulmars took to the air at 1212. By 1220 the fighters had gained enough height to join in the patrol. They were directed towards the same elusive Ju88, which was sighted at 1225.

This time the Fulmars were in a favourable position and were able to make a good attack run. The Ju88, apparently not significantly damaged, retired to the north-west.

All four of these Fulmars landed on HMS Formidable at 1310.

Formidable opportunity

After sweeping along the coast towards Alexandria in a hunt for convoys or fast supply ships, the Stukas of II/StG 2 were at the edge of their range and preparing to turn back.

This is when Oberleutnant Bernhard Hamester spotted Force A and the ultimate target in the war for the Mediterranean: a British carrier.

He did not hesitate. He immediately led his staffel in for the attack. The other formations followed suit.

Raid Warning

The last remaining available Fulmars, Brown Section, were flown off at the same time the Grey and Red Sections came in to land.

It was directed towards a contact that the radar office had been tracking since 1240 at a distance of 87 miles. By 1253 the signal was shown to be closing with the fleet, and by all indications it was a large group.

Force A was logged at 1300 as being some 90 miles north-east of Bardia. At 1310, the Battle Squadron was recorded as being 150 miles from Kaso Strait. By the time HMS Formidable launched Brown Section at 1310, the Fighter Controllers had reported the raid appeared to of several formations ranging from 30 to 39 miles in distance.

Another set of contacts had been made to the west: these were 47 miles, 58 miles and 61 miles away respectively.

Brown Section, which had not had enough time to gain effective operational height, was directed towards the enemy’s position at 1318. The hostile aircraft were quickly sighted some 5000ft above the Fulmars.

Brown Section’s Observers reported seeing 17 Ju87s, 11 Ju88s and a number of supporting Me110, Me109 and He114s.

They were good in their count.

German records reveal the attacking force was made up of 17 Ju87Bs from II/StG2 which had flown out of North Africa. They had been joined by 11 Ju88s of LG1.

It was common for British pilots to believe Stukas firing at them with their fixed forward machine-guns were in fact fighters, and misidentify them as such. There appear to be no records of German fighters taking part in the action..

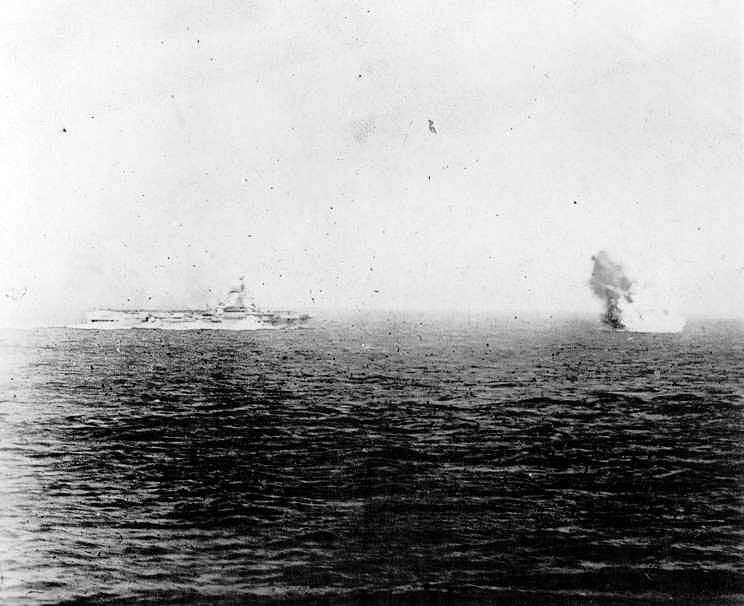

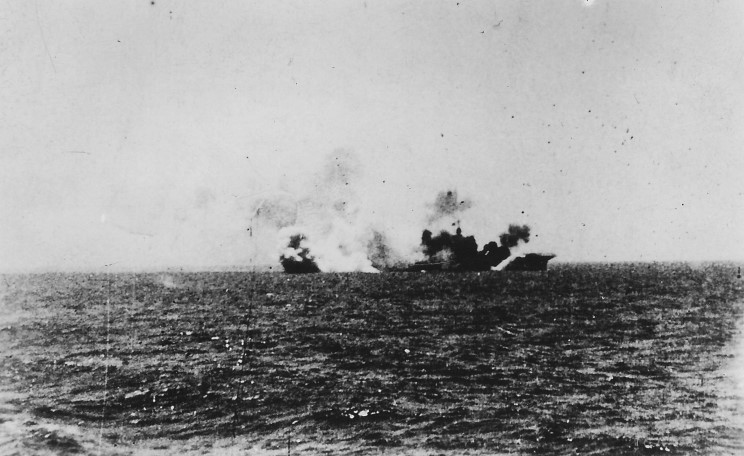

Attack One

The fleet’s high-angle anti-aircraft armament opened fire at 1321. But the large number of different strike groups approaching from different directions soon threw the defence into confusion.

The Germans believed HMS Formidable had been caught flat-footed. They thought she was in the process of recovering aircraft and therefore not in a position to launch fresh fighters to defend herself.

According to German accounts, the first Stuka formation was from II/StG2 led by Major Walter Enneccerus. This group had previously taken part in the attack on HMS Illustrious. Oberleutnant Bernhard Hamester leading 5 Staffel spotted Formidable and took advantage of the opportunity by attacking at once.

Staffel 4, led by Oberleutnant Eberhard Jakob, and Staffel 6, led by Oberleutnant Fritz Eyer, immediately followed suit.

HMS NUBIAN - LETTER OF PROCEEDINGS AND REPORT OF DAMAGE TO HMS NUBIAN AFTER ACTION WITH ENEMY AIRCRAFT - 26TH MAY, 1941

... At approximately 1320 on May 26th., when NUBIAN was in position "B" of screening diagram No. 6A screening the Battlefleet an attack was made on our forces by a large formation of enemy aircraft consisting of JU87s and JU88s. As the attack developed NUBIAN opened fire over the fleet with umbrella barrage. It soon became apparent, however, that the leading enemy units were attacking the screen and two definite attacks were made on NUBIAN, one by a JU87 and one by a JU88. Speed was increased to 26 knots (maximum available) and the ship manoeuvred to avoid the bombs which missed. The fleet was then attacked and the umbrella barrage was recommenced. Shortly after fire was opened it was observed that FORMIDABLE had been hit. A number of enemy aircraft then passed down NUBIAN's port side at a fairly low elevation and fire was transferred to them. At this moment one of the signalmen pointed out a JU87 which was approaching the ship at a low level from astern. I put the wheel hard to starboard and directed the guns on to this target. The machine was, however, fairly close and before effective fire could be developed it had reached its position and dropped a bomb. This bomb hit No. 4 mounting and exploded heavily...

Brown Section had been unable to attack the higher German aircraft before they commenced their bombing runs. But the Ju87s were low enough after their strikes for the Fulmars to engage.

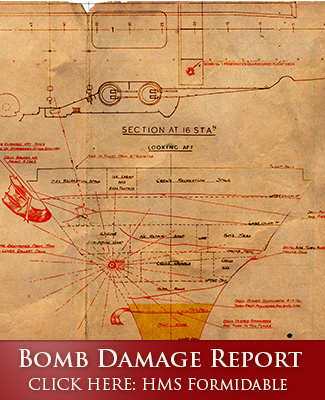

The dive-bombers plunged through the flak to strike HMS Formidable. There are conflicting reports as to whether they were carrying 500kg (1100lb) or 1000kg (2200lb) bombs. But the War Damage Report compiled by the DNO after the carrier had been repaired in Norfolk, United States, argues the damage characteristics them likely to have been 1000kg (2200lb) weapons..

Formidable’s two Fulmars gave chase to the departing Stukas. Each claimed a Stuka destroyed.

Brown Section was then forced to break away after being attacked by what they believed to be four Me110s. The Fulmars sought refuge within the fleet’s destroyer screen.

Brown 2’s Observer had been wounded four times in the leg.

In the confused swarm of attacking Ju87 and Ju88s, HMS Formidible’s command staff identified at least eight aircraft making attack runs on the carrier.

She was hit twice in a short space of time. Neither struck the armoured-box hangar.

Hot Landing

The Fulmars, low on ammunition and damaged, landed on the carrier at 1340 – shortly after the smoke and flames had been doused.

Whether through fatigue, damage to the machine or to the ship, Brown Leader’s Fulmar went into the crash barrier.

Attack Three

About 1352 another group closed to within gun range.

This formation also turned away without dropping bombs.

Attack Four

At 1400 a fresh group of enemy aircraft was detected at 55 miles distance. It was estimated to contain 12 aircraft.

At 1425 the formation carried out a high-level bombing attack. Their weapons fell around HMS Nubian and Jervis, at that time positioned in the outer screen some 5 miles from the main body of the fleet.

HMS Nubian had been hit aft and had her stern blown off. But the damage was mostly above the waterline, and she was able to continue at 20 knots.

Christopher Shores; Brian Cull: Air War for Yugoslavia Greece and Crete 1940-41

Two Fulmars flown by ex-805 Squadron pilots Sub Lts Sykes and Sinclair, had just landed when the attack commenced, and the two TAGs – L/ Airmen Freddy de Frias and R E Northfield – had just entered their Mess, where they were moaning that no lunch had been saved for them. Suddenly, recalled de Frias:

‘The bomb penetrated the flight deck aft of our Mess and blew out part of the bows underneath us. We were both dazed by the explosion but unhurt; even the Mess was undamaged apart from a bulge in the deck and lockers and other furniture strewn all over the place. We gathered ourselves up and left. A damage control party was squirting hoses into the hole the bomb had passed through. Really we had a miraculous escape because had the bomb exploded a fraction of a second earlier it would have blown out the Mess. As it was, it exploded (as far as I recall) almost on the waterline, right in the stern, which was why our casualties were so light.'

“By 1800 Cdr Atkinson considered that launches of Fulmars could recommence, although the catapult was out of action. Two aircraft were ordered off to patrol, bouncing over the battered, bumpy deck before becoming airborne, followed by two more 25 minutes later.”

Air Patrol

By 1542 HMS Formidable had recovered enough from her damage to fly off Fulmars.

Green Section, made up of two Fulmars from 803 Squadron, took off to provide air cover.

A single Fulmar of Yellow Section, also 803 Squadron, flew off as relief at 1805.

A variety of RAF aircraft had appeared over the fleet from 1532 onward, but communications and identification proved difficult. HMS Ajax opened fire on two Blenheim heavy fighters before the error was realised. Several flights of Hurricanes also made appearances over the fleet.

The final Fulmar was landed on HMS Formidable at 2015.

Shortly after, the carrier was detached with HMAS, Voyager, Vendetta and HMS Hereward for the refuge of Alexandria. HMS Decoy, which had just rendezvoused with Force A, was also assigned to the carrier’s escort.

The night passage was uneventful.

Shortly before dawn, at 0500, the TSRs were flown off to the FAA support base at Dekheila. What Fulmars remained airworthy were flown off to Aboukir at 0545.

Formidable entered Alexandria harbour at 0715. In all, nine ratings were killed and eight wounded in the attacks. Two of the wounded later died.

Tail-end Charlie ... HMS Nubian in Alexandria Harbour after losing her stern to a bomb while on the screen for HMS Formidable. Another "N"-class destroyer is passing in the background.

After Action

The consequences of losing HMS Formidable were immediate: On May 27 Convoy AN31 for Suda Bay was ordered to turn back in the face of overwhelming air opposition. The remains of Force A was attacked by 15 Ju88s and He111s. Barham was hit on “Y” turret, starting a serious fire which took two hours to contain. Two of her bulges were flooded by near-misses. Two bombers were claimed shot down and one observed to be damaged.

Admiral Cunningham ordered Force A to return to Alexandria. He had no answer for the relentless air attacks. The cruisers and destroyers, however, continued their courageous efforts to evacuate trapped Commonwealth troops until June 1.

The damage to Formidable was serious. The lack of available dockyards meant the carrier had to withdraw to the United States via the Suez Canal for repair at Norfolk Naval Shipyard. She was not available again until December 1941.

While in the United States, Formidable took delivery of a squadron of Grumman Martlet Mk II fighters – one of the first real steps to address the weaknesses of the stoic Fulmar.

The “experience” demanded by the Admiralty in its dispatches to Admiral Cunningham was well and truly learned – at least by those at sea.

Germany’s complete air control allowed an invasion to take place even though they had not established control of the seas.

Britain’s sea superiority could not be long maintained under intense air attack.

Another major lesson was that a single armoured carrier was unable to maintain the level of operation necessary to provide adequate air cover.

Letter from Rear Admiral, Mediterranean Aircraft Carriers to Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean

[ADM 199/ 810]

13 June 1941HMS Formidable’s operations, 25– 27 May 1941

Forwarded, concurring in the remarks of the Commanding Officer, H.M.S. ‘Formidable’.

2. The ship was handled admirably during the attack and the defence put up by the gun armament was spirited. The attack was successful because conditions favoured dive-bombing and without one man control the Pom-Poms are slow and inaccurate. Aircraft were very difficult to see against a misty blue background.

3. The behaviour of the fighter aircraft was as usual beyond praise and the direction of them by Commander Yorke was admirable.

Rear Admiral Boyd commented on the defence of Formidable:

“The behaviour of fighter aircraft was as usual beyond praise and the direction of them by Commander Yorke was admirable”.

But Captain Bissett would write in his report on the operation:

“From daylight onwards on Monday 26th May, there were frequent calls for fighters to drive off enemy reconnaissance aircraft. Three of these were shot down.

The small number of fighters available on board made it impossible to answer the above calls and maintain an adequate number in reserve to deal with bombing attacks. As a result, when the main attack developed on the Fleet, only two fighters were in the air and no more were available until the attack was over.”

In another assessment, Formidable’s Fighter Direction Staff ruled that Fulmars in the face of shore-based aircraft were simply not given enough time to reach interception heights by the detection range of the Type 279 radar. This made a standing fighter patrol essential, they advised.

Admiral Cunningham had always been impressed by the capability of even single carriers in his fleets:

“Whenever an armoured carrier was in company, we had command of the air over the fleet … and also gave us vastly increased freedom of movement.”

But, three months after the attack on Formidable, Admiral Cunningham wrote that he believed two carriers carrying five fighter squadrons were the necessary minimum to maintain adequate fighter coverage for the fleet. He felt there needed to be up to 18 aircraft in the air when the risk was most acute.

His request for two carriers was denied on the grounds of a lack of available ships.

Aftermath

Clearly HMS Formidable had below optimal numbers of operational aircraft when pressed into the desperate action to protect retreating Commonwealth troops and tired and harried warships operating under enemy air superiority.

Whether this was through the true belief that her patched-up air group was up to the task or simply a bloody-minded attempt to sate the demands of an ignorant Admiralty will never truly be known.

Was the sacrifice of HMS Formidable, and all the other Commonwealth Naval vessels sunk or damaged during the Crete campaign worth it?

Out of the 32,000 Commonwealth troops deployed to Greece and Crete, 18,600 were evacuated.

One New Zealand solider wrote:

“With a torch we flashed an S.O.S. and, to our tremendous relief, we received an answer. It was the Navy on the job – the Navy for which we had been hoping and praying all along the route”.

These words add weight to Admiral Cunningham’s declaration that it takes three years to build a ship, but 300 years to build a tradition.

Lessons learnt?

Message from Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean to Admiralty

[PREM 3/ 171/ 4] 0930, 20 August 1941971. Request that consideration may be given to stationing 2 aircraft carriers in Eastern Mediterranean during next winter.

2. Primary role of their aircraft would be fighter protection to fleet thus giving full scope for surface forces to attack shipping route, for bombardment, minelaying etc. Offensive operations by torpedo spotter reconnaissance aircraft would also be continued as in the past.

3. No operations by surface forces can be conducted in Eastern Mediterranean without air protection. The protection that can be given by shore based fighters is limited by range of aircraft to that required for defensive operations only, and there are in any case insufficient fighters available for requirements of all services.

4. Given adequate fighter protection fleet can move anywhere and scope for useful operations is very great. This ability to attack anywhere must involve enemy devoting considerable air strength for protection of important points with consequent reduction in forces available elsewhere. It may also involve him in desperate measures which we would be well prepared to meet.

5. Requirements for strong fighter protection while still allowing carriers to embark an adequate striking force, can just be met by 2 carriers, with one spare fighter squadron and one spare torpedo spotter reconnaissance squadron available ashore.

6. Basis of calculation of fighters required. Assuming an operation lasts about one week, as is normal for extended operation in Ionian [Sea], the following fighter patrols will be required:

(i) Continuous patrols by 4 aircraft will be required during approximately 12 hours of daylight daily throughout period. (ii) Patrols will have to be increased to not less than 6 Fighters during period when there is some risk of air attack, i.e. for period of about 8 hours for 5 days. (iii) Patrols will have to be increased to 18 Aircraft during period when there is great risk of air attack, i.e. for about 6 hours on 4 days. (vii) Total number of flying hours required for above – not allowing for overlaps or landing times – is 704 hours. (viii) Fatigue will not allow each pilot doing more than 1 ½ operational flights per day for 7 days continuously. Assuming each flight is 2 hours, each pilot will be capable of doing 21 hours. Total number of crew/ aircraft required will be 35. Allowing 33 ½ per cent margin for losses by accident or in action or aircraft unserviceable for various reasons, total number of fighters required is 47. (ix) It is considered a spare squadron should be available to provide for period of rest and training. (x) Eastern Mediterranean is excellent operating area for carriers in winter when weather conditions are bad at home. If Mediterranean campaign goes well during winter they could be transferred to other areas in the Spring by which time they will have reached a high standard of efficiency. (xi) Assuming 2 carriers will comprise H.M.S. INDOMITABLE and one H.M.S. ILLUSTRIOUS class, Squadrons required are 4 Torpedo Spotter reconnaissance aircraft and 5 Fighters of which 2 Torpedo spotter reconnaissance and 3 Fighter squadrons are now on station. (xii) Type Fighters. It is considered 3 of Fighter Squadron should be single seaters i.e. Martlet 2 or Sea Hurricane. (xiii) Facilities in Egypt. It is expected Naval resources in Eastern Mediterranean should be adequate by Mid October to Service 9 1st line Squadrons. (xiv) Supply aircraft. If supply of Albacore is also maintained at the rate of about 20 per month, reserves should be adequate to maintain 4 Squadrons… (xv) Though 2 Carriers have been damaged in Eastern Mediterranean it is considered if 5 fighter Squadrons are available they should be able to meet a high proportion of whole German Air Force with confidence.

16. In view of strength of German Air Force in Mediterranean at time of these attacks it will be appreciated number of fighters proposed should provide very satisfactory degree of protection.

17. It is considered this Fighter Squadron, together with fire of Fleet, should provide such formidable target to attack, that it must result in destruction of many enemy aircraft, or alternatively a sense of frustration, and hence loss of morale, at difficulty of task …

Minute from First Lord of Admiralty1to First Sea Lord

[PREM 3/ 171/ 4] 21 August 1941

Request for aircraft carriers in Eastern MediterraneanI have read the telegram timed 0930/ 20th August, from Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, and I must say that I feel considerable doubt as to whether it will be possible to meet his request.

CLICK on the above image to go to the original pdf source. CLICK HERE to be taken to armouredcarriers.com analysis of HMS Formidable's bomb damage.