“ Nobody would pretend that the Seafire had been the ideal carrier fighter, but I had probably deck-landed it more than any other pilot and had never felt anything but exhilaration at the challenge that it presented.”

Service History

The first operational Seafire unit was 807 Squadron which took delivery of its machines in June 1942 – too early to see service in August’s Operation Pedestal convoy run to Malta.

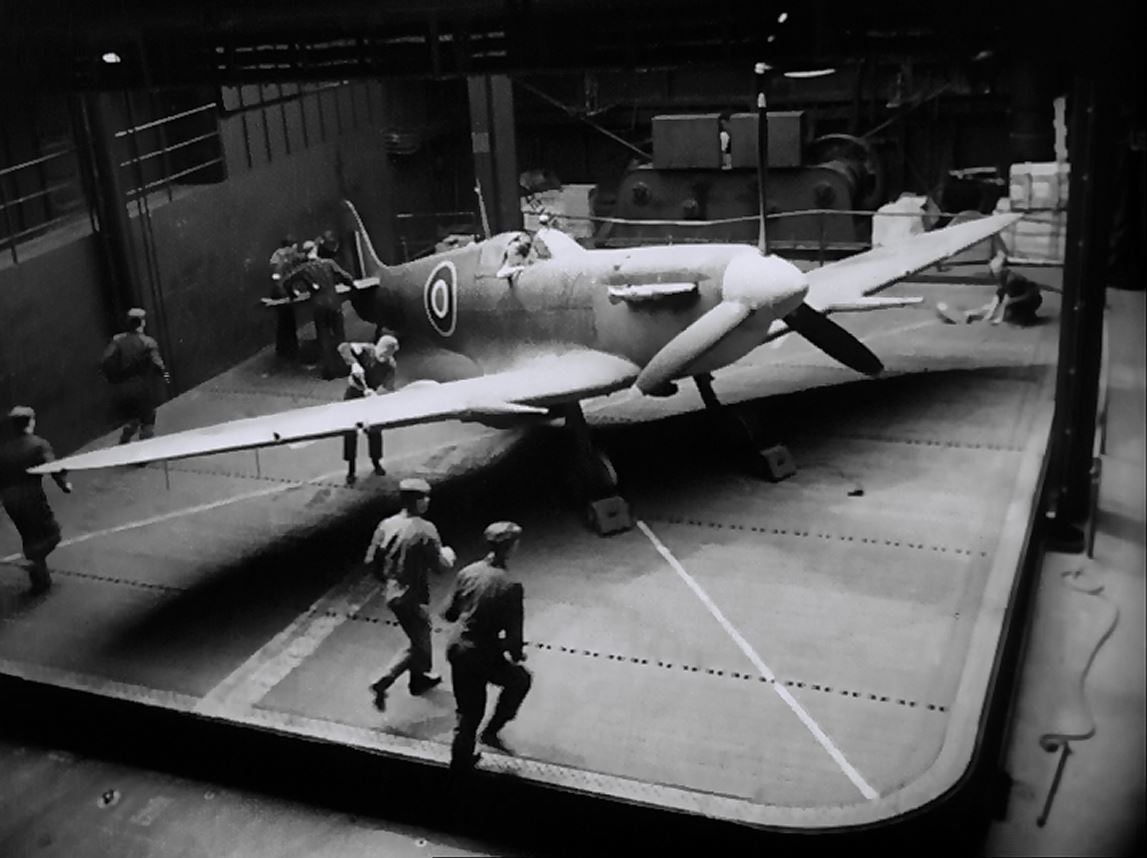

The second squadron would be 801, with the new machines arriving in September. The squadron was assigned to HMS Furious which had unusual “T”-shaped lifts which would allow the non-folding early Seafires to be stowed in the hangar.

Conversion of Sea Hurricane squadrons to the Seafire took place at a steady pace during 1942 until mid 1943.

The Seafire, while retaining much of the spectacular performance and handling of its land-based sibling, was nevertheless a contentious and controversial aircraft. It took considerable skill the land the fighter on a carrier's deck, and equally considerable effort to eventually iron-out its key deficiencies.

Rear-Admiral Vian, who commanded Britain's last and largest carrier fleet, did not seek to hide his displeasure of the Seafire. His disparaging reports inspired his pilots to great lengths to prove him wrong - with innovations including the adaptation of surplus RAAF Warhawk drop tanks to suit their nimble little fighters.

The full effect of the years during which the Fleet Air Arm had been to rely upon adaptations of Royal Air Force machines, designed for short-range land operations, was now to be felt. Seafires, derived from the Spitfire, had an hour’s less endurance than the Hellcat’s and Corsairs, and this was to be an acute embarrassment to us when we joined the American Fleet. Designed for operation from the long, paved runways of airfields, their undercarriages lacked the strength to stand the frequent heavy landings inherent in deck operation. Their crash-rate was therefore high compared with American types. This, too, was to be a source of trouble in the time to come.

Operation Torch

The allied-landings in North Africa on November 8, 1942, would give the Seafire’s their first test under combat.

Two squadrons (801 and 807) were operating from HMS Furious (which could stow the non-folding aircraft in its hangar) when the carrier was assigned to provide air coverage for the landing of US troops. The Seafires carried temporary US-style “star” markings for that specific operation only. The Seafire’s “first blood” came during these landings – a French Dewoitine D520 shot down by an 801 Squadron pilot near Oran. A Ju88 also was claimed by 880 Squadron.

HMS Formidable also carried Seafires during Torch – a deck park of 885 Squadron. HMS Argus carried 880 Squadron.

Operation Husky - Sicily

HMS Formidable’s handful of deck-park 885 Squadron Seafires again saw action in July 1943 over Sicily.

HMS Indomitable – with its large forward lift capable of carrying the non-folding fighters down to its upper hangar – operated 807, 819 and 880 Seafire squadrons. But her deployment was cut short after being torpedoed by a lone Ju88.

Operation Avalanche – Salerno

“Meantime on that morning, the forty-eight Wildcats could have left their base on the Fleet Carriers to land comparatively easily and safely on the four Escort Carriers from where they were better able than the Seafires, in most respects, to take on the role vacated by them. The Escort Carriers, I should add, already held stores of Wildcat ammunition and spare parts. The whole exchange could have been completed in less than an hour with Unicorn and its sixty Seafires holding the fort. But there was no such decisiveness from Vian who, in truth and reality, understood absolutely nothing about the capabilities of the aircraft under his command and was completely out of his depth in this situation.”

This was the action that would give rise to the Seafire’s reputation as prang-prone compromise. But does the full story paint a different picture?

The plan was that, on September 9, 1943, the allies would engage in a bold move to out-flank axis forces dug-in on the Italian mainland. Landings would be conducted in the Gulf of Salerno – 200 miles from the closest fighter bases in Sicily.

Defensive air cover, however, was an imperative. A lot of good fighters were needed to provide a constant umbrella over the beachhead.

The answer was seen to be the Seafire.

They were expected to be the primary defensive fighter force for the beachhead for the first 24 hours.

Some 106 Seafire LF IICs were assembled in 11 squadrons.

HMS Unicorn surrounded by the escort carriers of Force V off Salerno

HMS Illustrious (894 Squadron) and HMS Formidable (885 Squadron) formed part of the fleet protection screen, Force H. They carried deck-parks of up to 10 Seafires each.

Most of the Seafires would however be operating from the support carrier HMS Unicorn (809, 887 and 897 Squadrons) and the escort carriers HMS Hunter (899 Squadron and 834 Flight), HMS Stalker (880 Squadron and 833 Flight), HMS Attacker (879 and 886 Squadrons) and HMS Battler (807 and 808 Squadrons). These comprised Force V under the command of Rear Admiral Vian.

Rear-Admiral Vian would later write in Action This Day:

“I was altogether inexperienced in the operation of a force of aircraft carriers, but this deficiency was in part repaired by the unparalleled generosity of Rear-Admiral Clement Moody, who lent me his own Chief Staff Officer. This was no less a man than Captain Guy Grantham, lately Flag-Captain in Naiad… Moody, who might well have been disappointed that the command of the independent inshore carrier force had not fallen to himself, was entirely unresentful, and went to endless pains in helping Captain Grantham and me to produce a workable flying plan.

The heavy burden of providing combat air patrols was expected to be carried by the little escort carriers and their Seafires for the first day only. By day two of the invasion, the idea was for land-based fighters to be flown-in and operated from hastily established grass fields and a captured airstrip.

Seafires take off from the deck of the escort carrier HMS STALKER

The plan began to fall apart even before first combat.

Doubts were raised shortly after the carrier force set sail: Most of the Seafire pilots had very little experience in their new machines – yet alone in landing one on a carrier.

This was compounded when September 9 dawned with virtually no breeze over the beachhead. Struggling to maintain 17 knots, the “Woolworths” carriers were simply incapable of generating sufficient “wind over deck” to provide safe landing conditions for their charges.

To make matters even worse, the waters off Salerno was regularly covered with mist - obscuring the horizon and making it extremely difficult for pilots to properly orient themselves on a landing approach.

Rear-Admiral Vian, in Action This Day:

“The difficulty here was that, for necessary reasons, our Force was allotted only a small sea area off Salerno from which to operate aircraft. The maximum speed of our “Woolworth” carriers was only seventeen knots, and they must turn into the wind for flying aircraft off and on. The problem was how, with so little speed, and whilst remaining within our area, to have the ships back at the leeward end in time for the next flying operation.

A Seafire after taking the crash barrier aboard the escort carrier HMS RAVAGER.

A Seafire trapped by its characteristic "float" upon touch-down about to go into the crash barrier aboard HMS RAVAGER.

The Seafires came in on their landing approaches at speeds regarded dangerous for most contemporary naval aircraft. Arrester hooks were torn off, aircraft slew off the side, undercarriage oleo struts collapsed… and, at worst, they bounced right over the crash barrier and into forward deck-parks or the ship’s island.

To make matters worse, the invasion became immediately bogged-down to the point of almost being rolled back into the sea. Instead of capturing Montecorvino airfield on the first day, it took four days.

Some 70 Seafires would be lost or rendered inoperable through accidents during these four days of intensive and difficult low-wind operations.

But the Seafires had to press on.

On the first day 265 Seafire sorties were flown over the landing craft and beachhead. An average of 20 fighters was maintained constantly over the exposed troops and equipment – as well as covering strikes by USAAF A36A Apache ground-attack aircraft (modified P51 Mustangs).

Seafires aboard HMS HUNTER. Note the "slipper" fuel tanks under the fuselage.

The first day’s Seafire operations began at 06.15am and ended some 13 hours later. Sorties lasted about 85 minutes – 60 minutes in the combat zone, with the remainder being spent in launch and landing. Each escort carrier could only range about four Seafires each launch cycle, while HMS Unicorn – which was never intended to be an operational carrier – could handle about eight.

Rear-Admiral Vian, in Action This Day:

“The operation of five carriers together was a novelty, as only of recent months had there been enough of them to form a squadron such as that in Force V. The control from a cruiser flagship was an experiment which proved successful, since the small escort carriers had very limited space on their bridges and for operations rooms. In Euryalus, far from the noise of flying operations, we were able to give all our attention to manoeuvring the squadron and to controlling the aircraft in the air. These included the fighters sent from Illustrious and Formidable of the covering force to give us protection while our own fighters looked after the landing area.

HMS BATTLER, ATTACKER and UNICORN with the cruiser EURYALUS in the glassy waters off Salerno.

Terrain-induced radar clutter severely hampered fighter direction efforts. Nevertheless, Seafires patrolling the beach-head would pounce and chase-away repeated attacks by bomb-carrying Fw190s and Bf109s. The largest such raid – at midday – involved a dozen enemy aircraft. The lack of radar direction meant first contact was usually visual, resulting in no successful interceptions.

Ground support operations were also curtailed: This time by persistent ground haze.

But the Seafire did succeed in preventing German aircraft from delivering their bombs on target. This was the primary objective of the defensive fighters.

A torpedo attack on Force H was rebuffed by the Martlets and Seafires from HMS Formidable and Illustrious. Another attack shortly after dawn on September 9 saw a flight of Ju88s intercepted and forced to flee by a patrol of Seafires.

A Seafire ends up on its back after a botched landing aboard HMS ATTACKER in the fickle winds off Salerno, 1943

Day two saw 65 Seafires able to respond to the call for extended air cover of the beleaguered beachhead. They managed to conduct 232 sorties, successfully disrupting more than 40 attacks. But the enemy fighters were able to outrun the Seafire IICs once they had jettisoned their bombs.

There was some success, however: The commanding officer of 897 Squadron , leading a patrol of four Seafires, spotted a flight of Bf109s at 12,000ft. Lt Cdr W.C. Simpson shot down two of the German aircraft while his wingman damaged a third. One Seafire sustained minor damage.

Day three dawned to continued calls for Seafire assistance. Stores – and aircraft – were beginning to run low aboard the escort carriers. Only 39 Seafires of Force V were ready for action after ongoing landing accidents in the becalmed bay.

Rear-Admiral Vian, in Action This Day:

By this time our available fighters had been greatly reduced in numbers, not primarily as a result of air combat, of which there had been a great deal fewer than had been expected, but owing to wastage from landing accidents.

It had been almost flat calm, and since the carriers could not exceed seventeen knots, the operation of landing on the very limited flight-deck was an exceedingly skilled one. The aircraft, nasalised versions of the Spitfire, not basically designed for deck-landing, lacked the necessary robustness, and were easily damaged by anything but perfect landings.

“If I may strike a personal note here, flying from HMS Illustrious I was one of the first Wildcat pilots to land on one of the Escort Carriers, HMS Battler, on the morning of the third day and I found the deep sadness and misery in that ship almost unbearable.”

Force H had it lucky: Their protective screen was deemed no longer necessary and the fleet – along with HMS Illustrious and Formidable – was withdrawn due to the fear of Uboat attack. They did, however, donate eight Seafires and eight Martlets to bolster HMS Unicorn’s air wing – restoring the carrier’s complement to a total of 25 machines (including 17 Seafires).

Force V’s fighters managed 160 sorties against a noticeably reduced intensity of German air attacks that day. But a new enemy – high-flying Do217 bombers carrying guided bombs – made an appearance over the fleet.

Day four saw a dawn patrol of Seafires launched, but then relief came at last after the emergency airstrip being constructed at Paestrum some 30 miles outside of Salerno was deemed ready. The escort carrier mechanics hurriedly restored as many Seafires as they could in order to deliver them to the airfield as aircraft from Sicily were now not expected to arrive for several days. Some 26 Seafires (two from HMS Stalker, four from Attacker, five each from Battler and Hunter, and 10 from Unicorn) would operate from the temporary field between September 12 and 15.

It was at during this phase that a flight of Seafires was bounced by two USAAF Mustangs (the Apache variants), one of which was shot down before they recognised each other as “friendly”.

FAA Pilot Hugh Popham's view:

From "Sea Flight: The Wartime Memoirs of a Fleet Air Arm Pilot"

I, with the remainder of the squadron (of Seafires from HMS Illustrious), was dispatched to Unicorn to augment her depleted fighter-strength.

Depleted it certainly was. The twenty aircraft the Woolworths (escort carriers) had sent ashore represented all that remained serviceable, out of a hundred or more, after the first three days of the operation. This was in part due to the complete lack of wind. The small carriers were only capable of a maximum of seventeen or eighteen knots, and this with no natural wind to supplement it, was on the low side for deck landing. In conjunction with a lack of experience on the part of many of the pilots, it resulted in accidents of truly astonishing number and complexity. They had come roaring in, shedding their hooks, thumping into the barrier, dropping into the park, going over the side, until the hangars were choked with wrecks.

We, with our bigger decks and higher speed, had no such troubles: in fact the squadron got through the operation without a prang at all, which somewhat mitigated the unfortunate impression which Commander Flying had formed of us.

David Brown, in The Seafire: The Spitfire that went to Sea, offers this account of the incident:

The American Army pilot bailed out and was unhurt. The Seafires landed without incident and the pilots were being de-briefed when an irate US Army Major in a flying jacket and wearing a pair of pearl-handled revolvers in cowboy-type holsters strode up, demanding to be informed as to "which of you Limey sons-of-bitches shot down my goddamn idiot Number Two?"

An analysis of the Salerno operations found the Seafires had shot down two and damaged four enemy aircraft. This came at a cost of 42 Seafires lost through accidents, though none had been due to enemy action.

At the height of the action, however, the Seafires successfully forced more than 40 fighter-bombers within one day to jettison their bombs and flee.

The fighter force had flown 713 sorties resulting in 32 deck-landing crashes which wrote-off the machine. Undercarriage failure claimed 17 aircraft while a further 24 were found to have sustained distortion of the rear fuselage. Four Seafires were lost to engine failure.

Many Seafires needed repairs after the propeller clipped the fight deck after catching an arrester wire. Spares were soon depleted. A quick “field modification” was applied through the trimming of the propeller by 2in which drastically reduced landing damage without any noticeable loss in performance.

The Seafires also performed above expectation: The highest daily sortie rate was a maximum of 4.1 per Seafire. They had been expected to only go up twice each on the first day.

HMS Hunter suffered the least accidents of the whole Seafire force. The pilots of 834 Flight had received intensive instruction in the art of deck landing by their RNZVR CO, resulting in the whole flight remaining operational.

Pilots from HMS Indomitable operating from the escort carriers after their own ship had been damaged by torpedo were among the worst crash offenders, blaming difficulty in adapting to the 30 per cent smaller flight decks and 10knot slower base wind-over-deck speeds.

The larger and faster HMS Unicorn, which had been designed to service aircraft – not fly them operationally – actually suffered the highest accident rate. Air turbulence over its deck was attributed as being the major cause of its 21 serious Seafire prangs, with a sideways wind sheer causing the undercarriages to collapse. Nevertheless, Unicorn – with an initial load of 30 Seafires – managed 197 sorties over the four days.

Rear-Admiral Vian expressed his displeasure with the Seafire's performance in his book, Action This Day:

“It was fortunate that the Germans did not bring their tactical bombers to the aid of their troops in any great numbers, or our little force of naval fighters would have been hard put to it to ward them off, after the first two days of operations, which was all we had been expected to cater for. As it was, our pilots were disappointed at the few opportunities given them to get into action.

However, many pilots would call into question Vian's own competence as a commander of carriers, citing his ongoing ignorance of the basics of flight operations - ignorance which included preventing fleet carriers from increasing speed to improve wind-over-deck for landing aircraft.

A Seafire goes around again after a failed approach on HMS HUNTER'S flight deck.

The ghosts of Salerno were partially exorcised when the Seafire and escort carriers were paired to cover another amphibious landing, this time along the shores of Southern France on August 15, 1944, in Operation Dragoon. HMS Hunter carried 807 Squadron, HMS Attacker had 879 Squadron, HMS Stalker 809 Squadron and HMS Khedive carried 899 Squadron.

The extra time available for working-up pilots - along with more favourable winds - resulted in the Seafire’s crash rate falling to one in more than 50 landings. HMS Stalker’s Seafires conducted 337 sorties in the 10 days of the escort carrier’s deployment.

Seafire LFIIIs used in Dragoon were used as fighter-bombers, carrying 500lb bombs in support of ground troops. It was one of only very few occasions this occurred.

Some of Salerno’s escort carriers moved to the Atlantic where the Seafire provided air cover for the convoys bringing in troops and supplies for D-Day.

For details on the Seafire during Operation Iceberg in 1945, please refer to the Task Force 57 section on the home page. Sections here for Palembang and other Seafire actions are to come.

Leading Air Mechanic B.M. Evans recalled:

I do not know its parent carrier, but it was obviously out of action and we were to land a few (Seafires) on. I was standing on the mainplane of a Corsair parked up front at the time, keeping one eye on what was landing. The Seafire appeared to approach rather high and fast, and when it touched down the undercarriage disintegrated. Our barrier was set for Corsairs, and the Seafire’s cockpit hood and pilot’s head were removed by the lower wire. At that moment all the guns fired, and I have no recollection whatever of moving, but I know I was pushing my nose through the deck thinking how ridiculous it was to have jumped after the guns had fired. To be honest, whilst the Seafire appeared to be good in the air, it left a lot to be desired as a carrier borne plane. We dreaded receiving them, and I cannot recall a successful landing.