PRELUDE

In January 1945, the British Pacific Fleet (in Ceylon) was ordered to Sydney for final preparations to fight alongside the Americans in the Pacific.

Perhaps.

The maelstrom of politics had continued to swirl between Washington and London during the second half of 1944. Argument and counter-argument flew between the factions. Some saw insult in fighting alongside their old imperial overlords. Others refused to accept that only US citizens should pay the blood price to defeat Japan.

Admiral Fraser and his staff were by now established in their Sydney headquarters.

He was well aware of the need to demonstrate that the Royal Navy remained a force to be reckoned with for the post-war world. And Britain needed to convince its own dominions, and people, that it could live up to its responsibilities.

It also had to prove it was up to the job.

Admiral Fraser had flown to Hawaii to meet Admiral Nimitz face-to-face. A series of meetings thrashed out both possibilities and likelihoods. Nimitz could not rule out the British Pacific Fleet being ordered to the south-west Pacific to support General MacArthur, but ensured Fraser he wanted the fleet where it would be most useful - the attack upon Japan.

Admiral Nimitz then asked Fraser to divert the British Pacific Fleet while enroute to Sydney to launch a major attack on the oil refineries of southern Sumatra on their journey to Australia.

Nimitz said he felt the poor performance of the Army Air Force heavy bombers in previous raids proved the facility needed the precision attacks of carrier strike aircraft.

Admiral Fraser immediately agreed.

Despite having reservations as to the readiness of his British Pacific Fleet, Fraser realised the request had just as many political implications as it did strategic value.

If he was to turn the request down, it would provide ammunition for Admiral King in Washington to further denigrate British operations in the Pacific.

But not all of the Admiralty back in London saw things the same way. Some forcefully argued against the operation, expressing fears that the target was well defended and heavy losses would destroy the fleet’s morale before it was even deployed to the Pacific. Any failure would also play into Admiral King's hands, they felt. Also, the Australian government had been promised the BPF would arrive before the end of 1944…

Admiral Fraser, however, carried the day.

What resulted was the largest operation conducted by the Fleet Air Arm during World War II – a two-pronged attack to put the facilities south of Palembang out of action.

The Royal Navy fleet carriers had returned to Ceylon where they restocked their airgroups from the reserve FAA squadrons training there. As many extra personnel and spares as could be accommodated were packed aboard for the journey to Sydney.

The fleet was re-designated Task Force 63.

A Ki-21 'Sally' bomber is surrounded by spray kicked up by the close-range anti-aircraft armaments of British Pacific Fleet carriers and escorts. A Seafire can be seen climbing out of the close-defence zone on the right-edge of the picture. This Sally, and up to six others, were shot down. This picture is taken from HMS INDEFATIGABLE, with an unidentified armoured carrier and the battleship King George V in the background.

Strategic overview

The city of Palembang sits in south-eastern Sumatra, about 270 miles south of Japanese occupied Singapore. It was a major road, rail and river transport hub.

It was also the headquarters for the Japanese occupation of Sumatra.

The reason for this was simple. Two large and strategically vital oil refineries were situated close by.

The two facilities sat about five miles downstream of Palembang on the south bank of the River Moesi. The river Komerine, which flowed into the Moesi, was a major landmark separating the two plants.

Sabotage attempts immediately before they were captured by the Japanese in February 1942 were insufficient. Both were back in full operation by the end of the year.

Between them, the facilities produced up to three million tons of crude oil each year. They also supplied some 75 per cent of the aviation fuel available to the Japanese.

The nature of both oil refineries were explained in detail to the intelligence officers of the British Pacific Fleet. Engineers who had worked at both plants had been called to Trincomalee to help in the construction of detailed models and prioritise specific targets.

Pladjoe: This facility had been built by Royal Dutch Shell on the west bank of the mouth of the River Komerine. It was the largest oil refinery in South-East Asia. It was a widely dispersed production facility with an unusual degree of redundant functions. It was a particularly complicated target.

Songei Gerong: This sat on the east bank of the Komerine, opposite Pladjoe. It had been owned by Standard Oil and was the second largest oil facility in the region. This plant was more compact and efficient – meaning it had fewer duplicated functions.

Key to the operation’s success would be surprise. Major Japanese fleet and air forces were based nearby. And Operations Robson and Lentil against Pangkalan Brandan may have awoken the Japanese to the emerging threat against their South-East Asian oil production facilities.

Two main strikes were planned, one against each refinery. Analysis of post-strike photo-reconnaissance images would then be used as the basis of a third ‘mopping up’ operation intended in taking out any key targets that had been missed.

To achieve these objectives, FAA aircraft would have to cross the Barisan Mountains and fly 150 miles overland. Not only would they face heavy flak, there was known to be six Japanese fighter squadrons from the 9th Air Division in the area. Four were based close to Palembang.

ALLIED ORDER OF BATTLE

Between them, the four fleet carriers were operating about 240 aircraft. This was the largest concentration of Fleet Air Arm aircraft ever embarked in a single task force.

Task Force 63

Flagship: King George V*

1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron: (242 aircraft)**

HMS Indomitable (Flag ACS1),

1839 Squadron (15 Hellcat I)

1844 Squadrons (14 Hellcat I)

857 squadron (21 Avengers)

(Edwyn Gray differs, with 6 Corsairs and 25 Avengers aboard Indomitable)

HMS Illustrious

1830 Squadron (16 Corsair II)

1833 Squadron (16 Corsair II)

854 Squadron (21 Avenger I & II)

Ship’s flight: (2 Walrus – ‘Darby’ and ‘Joan’ ***)

(Edwyn Gray says Illustrious was carrying 36 Corsairs and 18 Avengers)

HMS Victorious

1834 Squadron (18 Corsair II)

1836 Squadron (16 Corsair II)

849 Squadron (21 Avenger II)

(Edwyn Gray gives Victorious 19 Avengers)

HMS Indefatigable

887 Squadron (24 Seafire FIII)

894 Squadron (16 Seafire LIII)

1770 Squadron (12 Firefly I)

820 Squadron (21 Avenger II)

* The flag was temporarily transferred to Admiral Vian aboard HMS Indomitable as Admiral Rawlings was ill.

** There is considerable variation in the numbers of aircraft reported deployed on the Meridian operations. Most numbers used in the narrative below are from Hobbs’ excellent The British Pacific Fleet: The Royal Navy’s Most Powerful Strike Force. The summary above is from Hobbs' Carrier Operations which appears to list the original force as it departed Ceylon. Other sources are specified when quoted.

*** Most accounts list HMS Victorious as being base ship for the two Walrus SAR amphibians. But indications are they were carried by Illustrious at this point. Victorious appears to have taken her Walrus aboard at Sydney.

4th Cruiser Squadron

HMS Ceylon, Argonaut, Black Prince, Euryalus

25th Destroyer Flotilla:

HMS Grenville (Captain D), Undine, Ursa, Undaunted

27th Destroyer Flotilla:

HMS Kempenfelt (Captain D), Wakeful, Whirlwind, Wager, Wessex, Whelp.

Force 69: Underway Replenishment Group

Leader: HMS Urchin

Tankers: Echodale, Wave King, Empire Salvage, Arndale*

*Joined from Fremantle, WA

Click on the above for expanded views

AXIS ORDER OF BATTLE

The strike against Palembang’s refineries had the potential to become very ‘messy’.

Singapore lay just 270 miles to the north. British and American intelligence believed several Japanese battleships and cruisers to be stationed there. It was also feared German U-boats may be operating in the vicinity of Sunda Strait and the Cocos Islands.

All it would take was a lapse in security, or a chance early sighting, for a possible counter-force to be awaiting the British carriers.

A Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (Nick) fighter after the surrender of Singapore in 1945.

Japanese reconnaissance habits for the region were well understood. Irregular patrols ranged out some 435 miles from Sumatra’s coastal Mana airfield, flanking Cocos Islands.

The strength and state of the Japanese fighter defences, however, was poorly understood. The Japanese 9th Air Division of the 7th Area Army was operating six squadrons comprising roughly 60 Ki-44 Tojo fighters and 30 Ki-43 Oscar fighters. There was also an unspecified number of Ki45 Nick heavy fighters, as well as a reconnaissance flight of at least four Ki46 Dina twin-engine heavy fighters.

Three squadrons (made up of Oscars and Ki45 Nicks) had recently been transferred from the Philippines in December. One had arrived from the Celebes earlier in January.

Palembang itself was defended by four squadrons operating from a ring of airfields carved from the surrounding jungle (Lahat*, Lembak*, Talangbetoetoe*, Martapura*). All were within 40 miles of the refineries.

A Ki-21 Sally is pictured flying over dense jungle.

9th Air Division, Sumatra

21st Hiko Sentai (Palembang**): Ki45kai Toryu (Nick)

26th Hiko Sentai (Betung**): Ki43-II & III Hayabusa (Oscar)

33rd Hiko Sentai (Bersun / Betung**): Ki43-III Hayabusa (Oscar)

64th Sentai detachment (Betung**): Ki-43-II & III Hayabusa (Oscar)

87th Sentai (Lembak / Gelumbang**): Ki44 Shoki (Tojo)

58th Hiko Sentai: Ki21-II (Sally/Gwen)

1st Field Reserve Regiment: Ki21 (Sally/Gwen)

24th Independent Air Squadron*

71st Independent Air Squadron*

* Listed by John Winton in Forgotten Fleet

** Listed by Christopher Shores in Air War for Burma

It was also known some 250 front-line fighters and bombers were based nearby in Singapore and Java. Once again, early warning could see these rapidly reinforce Palembang’s defences.

The quality of the aircraft facing the FAA was mixed.

During briefings, pilots were warned the Japanese ‘should be able to give a good account of themselves but much will depend on how much warning they get and how good their individual pilots are’.

The older Ki43 Oscars were mostly in 'active training' squadrons operating in relative safety far from the front lines. By 1945 these were well and truly obsolescent, their nimble airframes in no way making up for its slow speed and light armament of two 7.7mm machineguns.

Active units were equipped with the newer Ki44 Shoki (Tojo). This had greater speed and climb, as well as a heavier armament of four 12.77mg or two 12.77mg and two 20mm cannon.

Ground Defences

Palembang city, and its adjoining refineries, were at the heart of a Japanese radar network offering an early warning network extending hundreds of miles. A central reporting and command center in Palembang was established to coordinate air and ground defences.

There were roughly 270 heavy anti-aircraft guns and mortars spaced in and around the refineries. That this was more than found in occupied Singapore is an indication of how important Palembang was to the Japanese.

The August 1944 raid by American bombers (which had flown a 20-hour mission from Ceylon to disable the site for just one week) also suggested the presence of barrage balloons. This was dismissed by Royal Navy intelligence officials who insisted photographic evidence revealed none were present. In fact, there were between 40 and 60 kept concealed, ready to be released upon an air raid warning.

One issue facing both the pilots of the FAA and modern historians is that many of the outlying districts and locations around Palembang had more than one name. This, combined with the FAA's partial use of simple designations as well as dispersal through as many as a dozen simple air strips, can make the identification of specific squadron locations difficult.

Gunners and deck crew pose for the camera aboard HMS INDOMITABLE. A censor has crudely attempted to erase the radar from the top of the starboard-aft high-angle director.

OPERATION MINE

“We had time for one big dress rehearsal ... Our four carriers worked like demons. Colombo and Trincomalee suffered heavy simulated attacks from Avengers and Fireflies, escorted by Corsairs and Hellcats; and every airfield in the island was subjected to ceaseless ground-strafing by swarms of fighters.”

This was full-scale rehearsal for Operations Meridian I and II held on January 13. The exercise involved a simulated strike on the city of Colombo in the morning, followed up by fighter sweeps over Trincomalee and Sigiriya later in the afternoon.

The Royal Air Force would act as the defenders.

The point was to rehearse the coordination between fighters, fighter-bombers and bombers necessary for the success of such a complex strike.

Henry "Hank" Adlam recalls in his book On and Off the Flight Deck:

From before dawn until dusk simulated attacks were carried out all day and nearly every one of the aircrews completed three sorties in the day. The sky above Ceylon seemed filled with aircraft diving and swooping about over the Island and perhaps it was fortunate that there were no collisions. It was an exhausting day and it was right that we were made to do it because, as we were to find, it was typical of many days to come in the Pacific. Nevertheless, two good and experienced Corsair pilots were killed making their final deck-landings of the day on HMS Illustrious. They were probably very tired and unable to summon up the full concentration required to deck-land that difficult and dangerous aircraft.

Norman Hanson, flying Corsairs as 1833 Squadron Commander aboard HMS Illustrious, recalled one of the tragedies in his book, Carrier Pilot:

Around 15.30 the fleet stood in towards China Bay and by 1630 the last flights were landing on. Four flights of us collected in the area astern of the carrier, waiting for her to turn yet again into the wind. Landing commenced. One or two Corsairs were safely on the deck when Graham-Cann approached the round-down. Normally a safe and dependable deck -lander, he made a bit of a mess of this one and drifted up the deck, failing to catch a wire. He hit the first barrier full on. His belly-tank unhooked with the sudden declaration, leapt forward and was cut in two by the propeller. A sheet of flame sprang out which, in a 30-knot wind, quickly engulfed the after part of the deck in a sea of blazing petrol.... The poor devil died as they carried him up the gangway of the hospital ship.

Hanson also wrote of seeing a splash on the approach circuit to HMS Illustrious after his Corsairs had refuelled at Trincomalee while waiting for the carrier to clean up the mess. The aircraft, piloted by Eric Rogers, had lost too much speed on its approach turn, stalled, and spun into the sea.

Few pilots ever escaped a ditching Corsair.

Norman Hanson would soon become one of them.

OUTFLANK: THE MERIDIAN OPERATIONS

JANUARY 16

The main body of Task Force 63 departed Ceylon at 14.30pm. The cruiser Ceylon and destroyer Wessex left at 17.00 after delays in receiving mail and spare parts.

The replenishment group had departed earlier, on January 13.

The fleet was expected to spend the next 20 days at sea.

But the force commander, Vice-Admiral Rawlings, was ill. He was confined to his cabin aboard HMS King George V. Control of Task Force 63 was therefore passed to Rear-Admiral Vian.

Over the next three days, as the force crossed the Indian Ocean, TF63 engaged in almost continuous training exercises. These ranged from night surface combat and gunnery through to torpedo attack and fighter direction.

Seafires were used to emulate Kamikaze attacks on January 17. But three of the four Seafires’ launched on this task suffered landing gear collapse due to the heavy roll of HMS Indefatigable sailing in a long swell.

It was just the first of a string of incidents that would draw the ire of Vice Admiral (Carriers) Vain.

Sub-Lt John Haberfield of the Royal NZ Naval Volunteer Reserve, HMS Indomitable. Six days after this photograph was taken, he was shot down and taken prisoner by the Japanese. He was murdered by being beheaded on Changi beach on July 31, 1945. He was 26.

“I soon found that a carrier— its thick steel flight deck acting as a sort of cauldron— was undoubtedly the hottest type of ship afloat. Tropical uniform made the most of any breeze, forced draft and fans large and small did their best, but one went about below in a perpetual sweat that soaked three shirts a day. An allied and unpleasant development for me was that for the second half of a four-hour watch on the bridge I found my legs becoming very painful from varicose veins, not an entirely new experience but never serious before.”

JANUARY 20

Task Force 63 arrived at the refuelling rendezvous, designated Position SA, at dawn.

The tankers were nowhere in sight.

A flight of Avengers were flown off at 07.00 on a search pattern, quickly locating the wayward Force 69 among frequent rain squalls, moderate swell and gusting Force 5 winds.

It took until 18.50 to refuel King George V, the cruisers and destroyers. The carriers held enough in their bunkers to avoid this chore.

HMS Ceylon and Urchin were detached to cover the tankers as Task Force 63 approached the Sumatran coast.

This map shows the flight paths of the strike forces of Meridian I & II for the attacks on the Pladjoe and Songei Gerong (dotted lines) refineries immediately south of Palembang city. Of particular note are the location of the Japanese airfields, and the relative position of the targets on the opposite bank of the tributary to the River Mosei.

OPERATION MERIDIAN I

“We had very little information as to the enemy’s fighter strength in the area and did not know his state of preparedness, so, besides a very strong fighter escort, another force of fighters was ordered to neutralize the airfields around Palembang; the principal airfield at Mana was also bombed by four Avengers.”

Lieutenant (A) Eric S.Rickman RNVR in 'My Palembang'.

I was an Avenger pilot in 854 Squadron in HMS Illustrious in mid-January 1945. Together with the largest fleet in British naval history, we left Trincomalee, heading south-east. During their occupation of SE Asia the Japanese forces relied heavily on the twin refineries at Palembang in Sumatra, which supplied half their oil and three quarters of their aviation spirit. Admiral Nimitz had asked for these to be put out of action, and because dive-bombing was considered more accurate than other methods, the Fleet Air Arm was given the task. A few days later our CO summoned us to the briefing room, where we saw a superbly detailed model of the refineries.

‘This, gentlemen,’ he said, ‘is our target, and our job is to flatten it, which will probably take two strikes at least. You will study this model daily, till you know it backwards. You have about two weeks.’

Two intelligence officers then briefed us. They did not know whether the Japanese had radar yet, but there were horn-locator sites on the coast, and a balloon barrage was very likely, plus a heavy AA defence.

The first strike of Operation Meridian was scheduled for January 22.

The plan was for 12 Avengers to be launched from each of the four carriers with four 500lb bombs each. These numbers were selected based on calculations on how many aircraft and bombs were needed to destroy the target, and how many each carrier could launch in a single range.

The Avenger squadrons were divided into two wings. No. 1 Bomber Wing included 857 Squadron from Indomitable and 849 from Victorious, while No. 2 had Illustrious’ 854 Squadron and 820 from Indefatigable.

The carrier flight deck range also balanced the number of fighters deemed necessary to cope with the expected Japanese opposition in the air. The planned figure was 16 Hellcats and 28 Corsairs. The Air Coordinator’s flight of four Corsairs would join the escort force if necessary.

These were to be distributed between top cover, middle cover, left, middle cover right, bow close escort and stern close escort positions.

The fighter pilots were ordered not to leave their escort positions to strafe targets of opportunity.

The critical time was expected to be the 15 miles between the target to the assembly point for the return to the fleet.

Twelve Fireflies from 1770 Squadron would be given a double role, suiting their fighter-bomber designation. They were to open the attack with a strafe of plant defences, with their four 20mm cannons armed with armour-piercing and incendiary ammunition. They would then cover the Avengers during their return flight. Hobbs, in The British Pacific Fleet, says no rockets were used as the Fireflies needed their wing-mounted drop tanks. But other accounts - including Firefly squadron leader Cheeseman's memoir - state they were used.

The Avengers were scheduled to attack 40 seconds later – at 40 second intervals. These were to first bomb a list of mandatory targets, followed by targets of decreasing priority if the primaries were destroyed or obscured by smoke.

While most of the bombs were set for direct-contact, up to 5 per cent were to be given delays ranging from one hour to two days. This was to interrupt fire-fighting and repair operations at the oil plants.

The responsibility of Air Coordinator fell to Royal Marine Major R. C. Hay, DSO, DSC, aboard HMS Victorious.

His task was to ensure the attack was conducted effectively and efficiently.

“Then the weather took a hand. The inter-tropical front, a belt of high winds and torrential rain, made air operations impossible. I was forced to order a postponement of twenty-four hours. On the following night conditions were no better. Once again we headed out to sea for the day.”

JANUARY 22 & 23

The day of the planned operation arrived, and the carriers took up formation at the designated flying-off position some 70 miles east of Enggano Island. But the weather was atrocious.

High winds whipped up the sea, and torrential rain flooded the decks and blinded pilots.

Deck crews struggled through the sleet to rotate deck park aircraft with those in the hangars to minimise their exposure to the weather. Operation LIGHT had proven to the British just how vulnerable deck parked aircraft were to flooding from rainwater.

The fleet took up station again shortly before dawn on the 23rd. Again, the weather was too poor for the successful launch of a strike.

JANUARY 24

Dawn broke with the promise of clearing weather. The thinning cloud layer was at 20,000ft, offering visibility of about 50 miles.

The Barisan mountains of Sumatra were now within sight of the fleet. To the west was Enggano Island.

Deck crews ranged the strike in the lifting gloom, illuminated only by the soft blue hand-torches they carried.

At 06.15, at the designated Position TA, the carriers turned into the gentle south-easterly breeze and began launching.

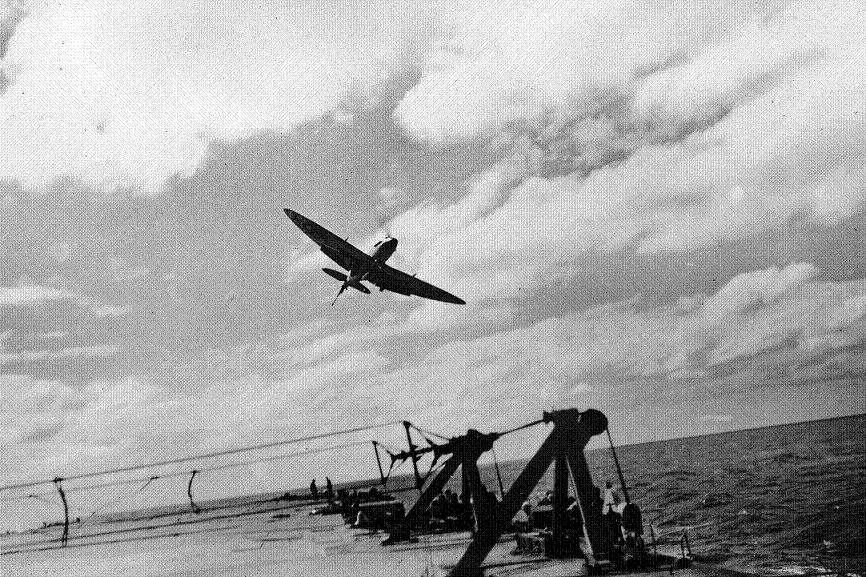

An Avenger of HMS INDOMITABLE's 857 squadron takes off.

“In the crystal-clear weather a protracted running fight might have developed, had the Japanese been thoroughly prepared. As it was, our aircraft were unmolested until they had almost reached their objective.”

LAUNCH

The long-legged fighters were the first to take flight. Sixteen Hellcats were soon joined by 24 Corsairs. The bombers, made up of 45 Avengers, followed shortly after.

HMS Illustrious launched the first few Avengers by catapult to ensure she could get the maximum number of aircraft off as quickly as possible.

Nevertheless, the strike was soon to be two Avengers short. HMS Indefatigable had pitched into the trough of a wave at an unfortunate time – just as the chocks were removed from one Avenger of 820 Squadron to allow it to move into take-off position. It surged forward, ramming another in the range. Both were damaged.

The duty recovery carrier, HMS Victorious, was soon to be busy. Four Avengers and two Corsairs dropped out of the forming wing for emergency landings. They were suffering engine and electronics problems – largely caused by the preceding days’ weather.

Victorious, despite being delayed by the emergency landings, managed to launch one replacement Corsair as well as her own scheduled second-range contribution.

By 07.04, the strike force was headed towards Pladjoe. It had roughly 180 miles to cover, including steep mountain ranges, to reach Palembang.

The Avengers lumbered upward at barely 400ft per minute, while travelling at 140 knots, to a height of 7000ft. Once over the mountains their cruise speed improved to 180 knots, climbing gently to 12,000ft.

1833 Squadron Commander, Norman Hanson: Carrier Pilot

My eye caught a hiccup of oily black smoke as it puffed from the funnel. The boys down in the boiler-rooms were flashing up more burners to increase speed. So it wouldn't be long. My aircraft conveyed the vibration through to my backside. She really was opening up the taps!

Wings came up on the Tannoys.

'Fighters start up!'

There was the usual brief pause while the lads moved to safety, away from the reach of those deadly propellers which would soon be thrashing the air, lethal and invisible. I was all set. All I had to do was to press the tit. The Koffmann starter coughed like an angry tiger and disappeared from view in a wreath of blue smoke...

Come on, Ian! Come on, let's go, for Chrissake!

He must have heard me, for the port oleo gave slightly - and the Corsair with it. We were turning to starboard into wind. Any second now! The ship was pushing on, turning on a sixpence with a great heel to port. I could feel the increasing wind speed over the deck.

I saw Colin wave away the chocks with a gesture from his torch. Then his torch came up, 'wound me up' and I was away.

Norman Hanson recalled the tension of keeping pace with the slow, heavy Avengers, as they climbed over the mountain range:

Once we levelled out on top, however, I was more than shattered to find that our eight Corsairs constituted the whole of Low Cover. Where the hell were the Fireflies? I hadn't the faintest idea what had happened to them at at this stage couldn't break radio silence to find out. We positioned ourselves over the centre of the bomber formation and hoped for miracles.

The RN carriers had begun hoisting the second range of aircraft to their decks immediately the first had cleared their bows. This included 24 Corsairs assigned to the RAMROD role and the 12 Fireflies of 1770 Squadron. There were also four Avengers and four Hellcats from Indomitable tasked with neutralising Mana airfield on the coast.

This launch was not completed until 7.20. Several FAA aircraft suffered mechanical failure while on the deck – including the Firefly of Major Cheesman, commanding officer of 1770 Squadron, which refused to drop its flaps. He was forced to hand control to his senior pilot.

Two more Fireflies were to suffer troubles while forming up. They made emergency landings on HMS Victorious. This left just nine Fireflies to open the attack on Pladjoe with their strafing runs.

HMS Indefatigable’s Seafires were not able to take part in the mission. Their endurance was simply too limited. This would also pose extra pressure on the fleet’s CAP. The fleet having to turn into the wind on the hour every hour. But there was also a human element to the CAP problem. Indefatigable at this point was carrying 22 Seafire F-IIIs and 16 LF-IIIs, totalling 38 machines. But only 35 pilots were available to fly them.

The first wave of the strike force crossed the coast about 07.20. This was noted by Japanese observers, who raised an air-raid alarm.

RAMROD

The three flights of eight Corsairs forming the RAMRODassigned to attack – and suppress – Lembak airfield flew their own low-level course through the Barisan mountains. They soon overtook the lumbering Avengers above.

Despite being late, the RAMROD surprised Japanese aircraft on the ground.

One flight acted as air guard as the other two swooped on the airfield targets, strafing targets of opportunity.

It was to be the most expensive element of the operation: Five Corsairs would be lost to accident and ground fire.

At Lembak, one Corsair was downed by anti-air artillery on the first pass, rolling over before cartwheeling through a row of parked fighters.

The RAMROD then moved progressively to Palembang and Talengbetoetoe airfields. But, by now, the Japanese were alerted to the attack. Gunfire was intense and few aircraft were left on the fields. One Corsair was shot down at each location.

Two Corsairs collided during one strafing run. One went into the ground, the other staggered back to the fleet minus 18 inches of its starboard wing.

Another Corsair pilot was seen to bail out of his damaged aircraft on the return flight. He was never seen again.

At one airfield a Corsair ejected its half-filled drop tank on a hangar. Its contents erupted in a sheet of flame, igniting both the hangar and surrounding structures.

About 20 Japanese aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground. A train was also hit outside Pajakoboeng as well as a power station.

Several Japanese pilots were, however, able to get into the air. Hideaki Inayama and his unit, the 87th Squadron, scrambled as the Corsairs flashed overhead.

Jerking back the stick, I jumped my Shoki into the air, retracted my undercarriage and simultaneously jabbed at the button operating the flaps, skimming along the tops of the coconut trees. No smell of burning! No unnerving knocking! My engine roaring smoothly! How those British pilots could have missed such a sitting duck I could not imagine, but I could thank my lucky stars that I was not already buried in the funeral pyre of my faithful Shoki.

Christopher Shores, in Air War for Burma, reports roughly half a dozen Ki43s of the 26th Sentai were able to get off the ground, along with about 10 Ki45s of the 21st . Most of the 87th got airborne along with an unkonk number of the 64th

“Fighters and bombers were handled cleverly, and there were many examples of exceptional skill and courage. For instance, one of the youngest Avenger pilots was Sub-Lieutenant F.R. Stovin-Bradford NNVR. His aircraft was one of those attacked and damaged by fighters as they approached the target. With his instrument panel and aileron control shot away, his engine on fire, his throttle jammed and one wheel hanging down, Stovin-Bradford pressed on indomitably to drop his bombs in the target area. Somehow he managed to reach the rendezvous and struggle back to the Fleet with his squadron, and to make a successful ditching alongside a destroyer which picked him up and his crew.”

STRIKE

It was fortunate that the RAMROD had caught Lembak’s fighters on the ground.

The Fireflies, because of the delay in their launch, only managed to take up their position as bow-escort to the Avenger strike force at 08.03 while at 20,000ft about 20 miles from Pladjoe.

Just one minute after joining the Avengers, when 15 miles from Pladjoe, the Fireflies spotted the first Japanese fighters approaching. John Winton describes this as a force of some 15 to 20 Tojos and Nicks, while most others include Oscars.

They also saw something unexpected: about 30 barrage balloons were rapidly floating upwards around the refinery, dangling long – lethal – steel cables beneath them.

It was an alarming turn of events.

Then the Japanese fighters began their attack from 15,000 and 30,000ft at 08.04. They dove straight through the Top and Middle Cover escorts - singling out the bombers as their targets.

Two minutes later, the Avenger strike leader ordered the Fireflies to divert and attempt to shoot down the barrage balloons which had now reached 6000ft. This was above their bomb-release height.

Only two Fireflies heard the order. The single radio frequency assigned for use in the strike was filling with calls as dogfights began to swirl above Pladjoe as some 25 Tojo fighters tangled with the top cover.

At 08.08 the Avengers entered the range of the Japanese ground defences as they began their carefullypredetermined approach. The Fireflies and two Avenger wings circled a distinctive bend in the Ogan River. The Fireflies broke off first, with each Avenger squadron flying over individually designated landmarks as a queue to peel off roughly every 40 second intervals and causing their attacks to come from different points of the compass.

The carefully laid plans were muddied by unexpectedly intense AA fire, as well as smoke and poorly defined landmarks. The Avenger commander also hesitated a few minutes to see if the 20mm cannons of the Fireflies had had any effect on the balloons.

At 08.14, knowing full well the balloons had been largely untouched, the strike commander ordered the attack. The first squadron, 857, dove from 7000ft and passed through the cables to drop their bombs from about 3500ft. The second squadron, 849, went in immediately after – three of its pilots narrowly avoiding balloons. The third squadron, 820, released its bombs from 2500ft – deliberately flying among the deadly invisble threads to increase their accuracy

Lt Beeny, 857 Squadron Avenger, letter to John Winton:

During the briefing we had been told that WT silence would be observed until we reached the target, and that we would bomb at about 3000ft. If a balloon barrage was spotted, the CO would issue new instructions about bombing. Everything went smoothly during the flight there – I didn’t hear a sound over the radio and it wasn’t until later that I learned that our radio was US (unserviceable).

As we approached the target at about 12,000ft we could see a carpet of brusting shells at about 10,000ft. We saw the CO begin his dive and so followed. When we were down to about 7000ft we were somewhat alarmed to see four 600lb bombs whizz by just in front of our nose. It was the senior pilot letting go his bombs (apparently they had been told at the target not to fly lower). Knowing nothing of these altered plans we continued down, only to see a couple of balloon cables flashing by. Down to 3000ft now, we spotted our target and pressed the tit to release the bombs, only to find we had a hang-up. Preparing to go round again, the air gunner warned that an enemy fighter was approaching. Taking evasive action and trying to find some cloud and being several thousand feet beneath our formation, we were on our own. The Tojo was still attacking, and the air gunner, thinking at last he had him in his sights, pressed the button – and the gun jammed!

Fortunately, for us, the CO of one of the fighter escort squadrons had spotted us and the Tojo, and had given him a good burst and winged him. But the Jap wasn’t quite finished yet. He next tried to ram us and was actually flying level with us when his tank caught fire and he rolled over and crashed just by his own aerodrome.

We made our way safely back after that and then had to land on with four 500lb bombs still aboard. Only one other thing could have gone wrong and that would have been if the bombs had been nose-fused. Fortunately there weren’t.

Smoke rises from the Plajdoe refinery in this post-strike reconnaisance photograph.

At 08.14, knowing full well the barrage balloons had been largely untouched, the strike commander ordered the attack. The first squadron, 857, dove from 7000ft and passed through the balloons to drop their bombs from about 3500ft. The second squadron, 849, went in immediately after – three of its pilots narrowly avoiding balloon cables. The third squadron, 820, released its bombs from 2500ft – flying consistently among the balloon cables to increase their accuracy.

Bombs were seen to burst among the power house and three distillery facilities, and several near-misses set fire to oil tanks. Thick oily smoke began to cover the target area.

Fortunately, none of the balloon cables claimed a victim. But one of 857’s Avengers was hit during its attack run and went down as it struggled towards the withdrawal assembly point. A Ki-45 Nick attempted to engage the Avengers as they peeled off on their attacks, but was shot down by Corsairs of the escort. Another fighter, identified as a Tojo, was also downed as it attempted to reach to the bombers.

By 08.20 the attack was over. Columns of thick black smoke were rising to 10,000ft.

Major Hay, observing the operation from with the accompanying three Corsairs of his flight, believed that only half the designated targets appeared to have been successfully destroyed.

A Firefly from HMS INDEFATIGABLE passes over HMS INDOMITABLE which has a range of Hellcats and Avengers ready for launch.

“In a time of two or three minutes the sky above the Avengers was an area of dog-fighting fighter aircraft and thus the Avengers were left to proceed almost unprotected to their target. In fairness to the fighter pilots, it is hard to break off from the intense excitement of chasing an enemy fighter and of having the upper hand in an air combat. After all, if a Tojo can be knocked down, it would be one less to harass the Avengers. Some of the fighter pilots such as the author did break away but only in time to watch as the Avenger crews started to make their courageous bombing attacks on the target.”

DOGFIGHT

While the Lembak airfield was successfully suppressed, the lack of simultaneous attacks on the remaining two airfields allowed the Japanese to get significant numbers of fighters into the air.

These had been loitering at about 15,000 and 30,000ft above Palembang.

They proved to be enough to saturate the FAA Corsair and Hellcat defenders. All Top Cover Corsairs and about 12 of the Middle Cover Hellcats were locked in dogfights.

John Winton, in Forgotten Fleet, quotes Japanese Tojo (Shoki/Demon) pilot Major Hideaki Inayama of the 87th Sentai (Air Regiment) writing in The Royal Air Force Flying Review, Volume XV, No. 8:

At 1500ft two Avengers were flying southwards, their leader trailing smoke. Sitting ducks. I carefully turned in behind them, concentrating on the damaged avenger which still had its bomb doors open. Probably its hydraulics had been damaged. Six hundred yards, five hundred yards. Suddenly its ball-turret gunner opened fire. Red tracer slipped past my Shoki (Tojo), but I held myfire. Two hundred yards. I could clearly see the gunner in the ball-turret. Now I was flying in the wash of my quarry and my aircraft was bouncing around like a mad thing. Steadying up the Shoki I fired at point-blank distance. The bullets from my four 13mm guns ripped into the Avenger, its green-house canopy bursting into ragments, like leaves in a gale. Flames seared back from the port wing roots and the Avenger rolled on to its back and then fell away into the jungle below.

While some FAA pilots had to contend with experienced Japanese instructors, others came up against considerably ‘greener’ opponents - including 1833 Squadron Commander Norman Hanson:

“… one laddie … made an awful shambles of it. I saw loads of stuff coming over my wing, someone firing dead astern of us. I looked in my rear view mirror and there ws this Oscar as big as a house. Everything happened in split seconds, I was going to shout ‘break’ one way or another but before I could get the words out of my mouth or press the button the fellow disappeared and shot underneath me. Then, to my amazement, he appeared right in front of us, in absolute plan view. We all heaved back on our sticks and belted him. When you hit someone with point-fives, something goes. Chunks flew off him and he fell off sideways in a sort of tail glide. He was only the length of a room away from us. We damned nearly ran into him.”

Eight Japanese fighters were claimed shot down around Pladjoe. One Corsair, last seen with a Tojo firing on its tail, was never seen again.

Major Hay noted several twin-engine Japanese aircraft on the outskirts of the battle (likely Ki45 Nicks), possibly acting as combat coordinators. He would later write in the April 5, 1951 Supplement to the London Gazette:

“No noticeable difference was observed after three of these twin-engine aircraft had been shot down.”

As the airspace above Pladjoe began to clear, Major Hay made a pass and activated his oblique cameras to capture images for a post-strike assessment. His flight was then bounced by four Tojos, but Hay shot down two and his wing-men the remainder.

A flight of Indomitable’s PR Hellcats also covered the scene using new camera equipment brought aboard the day the carrier had left Trincomalee. They were also tasked with photographing known, and identifying any previously unknown, airfields in the area.

Henry "Hank" Adlam: On and Off the Flight Deck: Reflections of a Naval Fighter Pilot in World War II

Then suddenly came an excited call on the R/ T. ‘Bandits! Three o'clock up!’

There were specks like gnats in the sky growing larger at each second and becoming Tojo fighters as they dived fast towards the Avengers below us. Immediately came from our leader, ‘Break right – Go!’ Throttle wide open, guns set to fire, mouth dry, I turned hard and fired almost immediately ahead of one of the Tojos as it hurtled on its way past me towards the Avengers; I didn't see the actual hits but my bullets must have deflected him off his course. I turned the Hellcat half on its back and pulled it hard round to follow the Japanese down. He kept straight on down past the Avengers and, although by this time he was well ahead of me, I longed to follow because my Hellcat eventually would have caught him in the dive. But I remembered the strict orders that, this time, the fighter escort must not desert the Avengers.

Reluctantly I broke away from the chase and I remembered the basic rule to keep turning and look out behind and all around me. I found myself alone; my number two, Dick, and the rest of the flight were nowhere to be seen. But I was much nearer the refinery now and could see how huge it was and realise how vital a target it must be. An immense amount of flak was coming up at the Avengers who, by this time, had deployed for their attack. Moreover, as far as I could see the whole perimeter of the refinery was being protected by fat balloons tethered at about 3,000 ft. Nevertheless, the Avengers and the Fireflies too were pressing on with their attacks regardless of the balloon cables and the intense flak of all types coming up to meet them. Full marks to them all for sheer guts, I thought. But there was no point in my hanging around here now that they had made their attack and, much higher up, I could see the trails of the dog-fights that were still going on.

Sensibly, as it seemed at the time, I made straight for the rendezvous position, on the other side of the town of Palembang, to meet the Bombers and escort them on their return journey. I arrived to find most of the Avengers already there together with six of our other Hellcats. An awful lot of R/ T chatter was going on making it difficult to know who was doing what and where but the obvious action for me was to join with the few Hellcats now escorting those Avengers who, by now, were beginning to make their way back to the Carriers. The return was uneventful, no attacks were made on us and gradually the rest of the escorting force joined up. The time was only about 9.30 am when our Carrier group was ready to start landing back on board HMS Indomitable.

I didn't find out the whole story until the big de-briefing afterwards. I learned that the separate ‘Ramrod’ of twenty-four Corsairs from Illustrious and Victorious, which had set off at full speed to hit the Japanese airfields in advance of our main strike, had in fact arrived too late. The Japanese fighters had all taken off already and had been waiting for us at 20,000 ft; hence all the dog-fighting in the area high over the refinery.

1833 Squadron Commander Norman Hanson, in Carrier Fighters, gives this account of the experience of his Corsairs which formed the Close Cover escort for the Avengers:

"RATS!! Eleven o'clock up!!!

Top Cover was shouting the odds and the battle was on. The air became alive with warning shouts, orders to close up and all the natter that excitement generates. And then I could see them. Over to the north, pinpricks were hurtling downhill from a great height and contrails streamed out across the azure sky as our fighters pulled tight corners to get at them. The Avengers were now deploying for their bombing run and their line was lengthening. Christ! I could do with 20 more Corsairs right now! Suddenly a Jap levelled out over on the port side, coming at us like a thunderbolt, making his run to take the bombers below us on the beam.

'Break left, GO!!" and the flight wheeled over on to its wingtips. We gave him a burst head-on and he ducked. Whether or not we hit him I don't know; but fire from 24 machineguns of .5 calibre is enough to make the bravest put his head down.

I hadn’t turned the flight back to the Avengers before someone yelled ‘Rats, three o’clock up! !’and there were two more, belting in at high speed. Churchill had already turned his flight at one of them. We took on the other. One of the four of us must have been a damned good shot, for bits and pieces of it flew around as it dived down, down. The pilot had forgotten all about the bombers now; we had given him something else to worry about! There was a great temptation to chase him; but our job wasn’t to mount up scores. Our purpose in life was to keep them away from the bomber boys, whether we hit them or not. Now we turned back to the line of the attack. The Avengers were diving on their run to the target and were going like the clappers. The bloody great balloons were still up, floating between us and the earth like some fat, green reptiles with bright red spots. And I cursed the Fireflies. They were the great destroyers who were going to clear these ugly sausages out of the way for us; and as far as I knew their crews were' still sitting in the wardroom with their feet up, reading Lady Chatterley ’s Lover. Where the bloody hell were they?

An Avenger from HMS VICTORIOUS crosses the Sumatran coast.

“Their attack completed ... the Avengers made for their rendezvous fifteen miles to the west of Palembang. This had been unluckily chosen, as our aircraft ran into a heavy concentration of fire. Moreover, they found a number of enemy fighters lying in wait for them.”

ESCAPE

The scattered Avengers made their way towards their rendezvous point some 10 miles to the west of Palembang. But the landmark – a small island in the Moesi river – was partly obscured by cloud and there was an unexpected concentration of anti-aircraft guns near the city itself.

The Avengers had been vulnerable to attack as they left the strike area: almost the entire escort force was already engaged.

Eight Corsairs of the Close Cover struggled to clear the escape corridor. Only a few Middle Cover Hellcats remained above the Avengers. None of the Top Cover fighters were to be seen.

All were embroiled in dogfights over Pladjoe, some 30 miles away.

The handful of Fireflies fought valiantly to keep their charges safe, but two Avengers were lost during this critical phase.

820 Squadron’s senior pilot was flying with two other Avengers were attacked by Japanese fighters while on the way to the rendezvous point. Using corkscrew evasion tactics, he and his wingmen avoided damage. However, four out of the remaining nine 820 Squadron Avengers were damaged by either ground or fighter fire.

HMS Victorious’ Captain Denny was unimpressed by the reports of his Avenger pilots after the attack. He saw their departure from Pladjoe as a:

“naked procession with no recognisable cohesion or concentration either of fighters or bombers.”

But the top-cover commander, Lieutenant commander Tomkinson, pointed out his fighters had to guard a corridor some 10 miles long and 5 miles wide – even as he was already engaged by an equal number of fighters to his own.

The Japanese fighters gave up their pursuit of the retreating FAA strike wings at 08.26.

1833 Squadron Commander Norman Hanson, in Carrier Fighters:

We were searching out ahead, weaving all the time like bastards, when tracer flew past us, fired from astern. There in my mirror was an Oscar—it looked as though it was sitting on my elevators—with guns flashing along its wings. I had time neither to shout nor to break before it dived beneath us, only to reappear in a split second, pulling up in front of us, the length of two cricket-pitches away. We all heaved back on our sticks and gave it the works; no need for gunsights. The silly bastard was half-staled, sitting there like a broken-down old whore. Its port aileron took off and sailed over our heads. What looked like a section of flap fell away to our right. Someone must have hit the engine. The aircraft fell, smoking, down on the port side and Matt Barbour must have nearly flown through it. God knows how he missed it. I yelled and did an aerobatic turn to port where another fighter - a Tojo - was boring in. No - it was another Oscar. We gave it a long burst, tearing chunks out of the back end of the fuselage and tail section, and it sheered off to starboard. Jesus! Business was brisk and we were tearing around like frustrated virgins!

I straightened up on the line of the last Avenger or two and had a quick shufti around to see how the boys were faring. Reggie Shaw and Matt Barbour—Nos 3 and 4—had vanished. I did a quick scan around the sky. Not a sign. How had they gone? Had that Oscar got them? Certainly not the one we had hammered up front. They had been with me then. What about that last desperate turn from the bombers? Had the speed of my turn taken them by surprise? When you lose a fast-flying formation, you can be miles away before you realise it. I just couldn’t remember when I had last seen them. Whatever the reason, Jimmy Clark and I were alone. Winnie and his flight had disappeared—perhaps he was already on his way to the rendezvous on the far side of the target area. So we pushed off in that direction, diving to get up some more speed. Thick, black smoke was now obscuring a lot of the target and Ronnie Hay would be having a few words to say about that!

I was still worrying about Shaw and Barbour when a Nick rose out of an empty space - sleek, two-engined fighter. It came up like a rocket on our starboard side, very close; and the aircrew hadn’t seen us. I saw quite clearly the two Japs sitting side by side in the greenhouse. Jimmy was the nearer of the two of us and turned to give it a quick squirt. I lifted and horsed the stick over, firing over the top of Jimmy’s Corsair. A rash of bullet—holes appeared on the Jap’s port wingroots as he fell off to starboard, faster and ever faster, plummeting down to the chaos of the refinery below. Again for one fleeting moment I damn nearly followed him; but again I remembered what my job was—and it certainly wasn’t that——and flew on to the rendezvous.

We came up to some Avengers, all of whom seemed reasonably relaxed and unworried. One of their pilots looked up and gave me a grin and a ‘thumbs-up’. We formed over them and soon were joined by two more Corsairs—Victorious' jobs. There were still a few calls for ‘Rats’ probably some fighters loafing around upstairs waiting for easy pickings. One whipped in at the Avengers, and the Victorious boys, on the starboard side of the weave, sheered it away. There were Hellcats about 1,000 feet above in classic open formation. Things at our level remained a bit disorganised—no wonder !— and still someone was calling ‘Rats!’ A Jap scudded across in front of us — a Tojo, I thought. Looked a bit like a FW 190 — way out of range. It was a full deflection shot and I hadn’t more than one chance in 10,000 of hitting it. I let fly anyway, just for the hell of it. Then it was suddenly quiet! —Oh! So unbelievably quiet!—and for the first time I saw that we were over the mountains again.

MANA AIRFIELD

The four Avengers and four Hellcats from Indomitable arrived unopposed over their target. One Avenger, however, had to turn back with engine trouble.

The coastal airfield appeared largely inactive.

A single Dinah twin-engine heavy fighter was destroyed on the ground, with the remaining bombs falling on the runway and hangars.

One Hellcat pilot was wounded by flak.

“It all seemed rather impersonal until, after the fleet had withdrawn and relaxation in the Wardroom was the order of the day, I listened and watched for the first time while pilots and observers relived their doings with pithy and sometimes hilarious descriptions, plus much graphic gesticulation with both hands. Every now and again there was a pause as a name was mentioned and I knew that behind the scenes there was melancholy activity in the cabins of those who had not come back.”

LANDING

A Corsair on final approach to HMS Illustrious.

The aircraft began to enter the landing circuits of their home carriers about 09.12, though the main strike group arrived about 09.37. Among them, unidentified, as a Japanese ‘snooper’ aircraft. It signalled the position and (incorrect) composition of the Royal Navy task force before breaking north and escaping the CAP.

The CAP fighters also reported hearing garbled mayday messages calling for an emergency homing vector to the fleet. There was some confusion over the callsign: Was this a missing Avenger from 820 Squadron? Repeated attempts to confirm the aircraft’s identify and locate it via radio direction-finder failed. Eventually the aircraft signalled SOS and reported it was ditching. This incident was the subject of intense investigation. It was not until after the war, when the missing Avenger was found crashed near Pladjoe, that it was determined this was a fake call by Japanese intelligence operators attempting to locate the fleet.

An ASR Walrus from HMS Illustrious was flown off at 09.53 with a Corsair flight as escort to an arranged rendezvous point, Pisang Island, for any strike aircraft that been unable to make the fleet. It returned empty-handed at 11.31.

All aircraft were down by 10.25.

Task Force 63 then withdrew to the south-west at 22 knots.

No sooner had the fleet settled on its new course, at 10.27, than the air-raid warning yellow alert was sounded. Unidentified bogeys had been detected on radar some 42 miles to the north. These seemed to be forming-up over Engano Island, or engaged in an expanding box-search pattern.

The Corsairs of the high cap were ordered to intercept. But they were immediately recalled. It was realised their fuel state was too low for a long range intercept. A second flight of Hellcats failed to make contact.

A Corsair goes into the water after hitting the prop wash of the Corsair about to be trapped aboard HMS Illustrious. It is possible this is Norman Hanson's ditching, as described below.

1833 Squadron Commander Norman Hanson, in Carrier Fighters:

The blessed sea came up~safety! I felt like old Xenophon ——‘Thalasa! Thalassa!’ I could have yelped with joy. We struck out towards the Fleet, keeping a wary eye above and behind us. At last, beneath us, spread the pride of the Royal Navy. And how bloody marvelous they looked! Two great battlers in the centre; four carriers in square formation round them, spaced out with all the precision of guardsmen; and cruisers and destroyers as far as the eye could see. They were already into wind and we started to land on.

We sorted out our various carriers, waited a minute or two, then I led the flight (we had just been joined by a couple more of our Corsairs) up the starboard side of Illustrious and lowered hook and undercarriage. Undercart OK anyway; down and locked. About a mile up, then round to port in a great ISO-degree turn. Down 20 degrees of flap. Ten degrees more. There was something wrong. What in God’s name was the matter with the thing? The flaps just weren’t taking the speed off it. I started to juggle, working out how to go about the business of landing and sailed on, well past the stem end of the ship. Eventually, somehow or other, I got it down to manageable speed and turned in towards the ship. I as low — too low. Down to about 350 feet — and a long, long way astern. Should I go round again? No — Bats was giving me ‘Roger’ so I pressed on and gave it a bit more throttle to get some extra height. I was in a bloody awful position, but he obviously thought I would make it OK. Then from the port side came a Corsair, in a steep turn, doing its approach to the deck; and was upon me before I saw it. I heard the roar from its engine above my own — God! It was close! And the pilot couldn’t see me beneath his wing! I crashed the throttle wide open to clear out of its way and promptly stalled. I had collected all its slipstream.

My Corsair fell out of the sky like a stone, port wing down. I screamed. I knew, without a shadow of doubt, that I was done for. From 400 feet, in a six-ton aircraft, you don’t stand a dog’s chance. The stick was whipped out of my hand by the sudden stall and was far to the left, set as though in concrete. I took both hands to it—no good. I got my left knee behind it — still solid. The sea was coming up at me at a sickening speed. Any second now. Then the stick became free — I had regained flying speed. Thank God, I did the right things instinctively. I kicked the starboard rudder hard and she stopped spinning. I straightened up the wings and started to pull — gently, though. I didn’t want to go into a reverse spin, which a Corsair would do without any trouble. For one wildly optimistic moment I thought I was safe. The sea was close, horribly close and I was going fast now. But I was pulling out of the dive — gently, gently!

Everything went black, as they say.

“Our losses were not light - six Corsairs, two Avengers and one Hellcat failing to return. Nevertheless it had been a shrewd and succesful blow at the Japanese in a vital spot, and we planned to repeat it.”

MERIDIAN I: AFTERMATH

Assessment of the photo-reconnaissance images confirmed that the crude distilleries and run-down tanks had been hit as well as transforming and redistillation units, the boiler and electric power plants.

Roughly 30 per cent of the refinery complex had been destroyed. Intelligence services later determined the long-term production of the Pladjoe facility had been halved by the raid.

In total the Royal Navy lost six Corsairs and two Avengers. One Hellcat was also downed.

One Corsair and one Seafire suffered engine problems over the fleet. Both pilots successfully baled out.

Christopher Shores, in Air War for Burma, quotes Japanese records as claiming the following kills and losses:

87th Sentai: Eight aircraft lost shot down with the loss of four pilots. Another wounded pilot force landed. The fighter regiment claimed 15 kills and 13 probables - some shared with other squadrons and AA.

21st Sentai: Three pilots were killed, with six FAA claimed shot down.

64th Sentai: One pilot killed.

26th Sentai: Three pilots killed.

The behavior of the Griffon engine on the Fireflies continued to be cause for concern. Some aircraft had returned with as little as 97 gallons of fuel remaining, while others had 280 gallons. Renewed efforts were made to standardise the engine’s tuning.

Admiral Vian was livid about the performance of his Seafires. HMS Indefatigable had been pitching heavily in the steady swell. This had contributed to a string of Seafire landing accidents. Once the strike force had returned, Indefatigable was relieved of her CAP duty because of the incessant delays produced by the prangs. Captain Graham noted in his report that the pilots of No 24 Fighter Wing appeared dejected that evening.

Later, during the refuelling operations, fighter and bomber wing leaders assembled aboard the flagship, HMS Indomitable, to discuss their experiences.

The chief item of debate was the presence, or otherwise, of escorting fighters close to the Avengers during the vulnerable form-up period between bomb-release and return to the fleet.

Something had to be done to maintain discipline.

The issue of the balloons also drew heated debate. The Avenger squadron commanding officers wanted fighters dedicated to the task of clearing a rout for their bombers. After all, the whole point of the mission was to deliver their bombs on pinpoint targets - something that required safe low altitude release. Admiral Vian, however, was hesitant. He wanted to strip fighters from the RAMRODs and escort force to reinforce the CAP over the fleet.

No new orders were issued addressing the balloon threat before Meridian II. This would prove costly.

REPLENISHMENT

“While the Carriers were bobbing along at about two knots, tied by hoses to the tankers, the aircrews were subjected in the windless heat to a number of de-briefings and discussions about the next strike. The aircrews were lambasted again for their unnecessary chatter on the R/ T and general indiscipline in the air. Fair criticism, but the thought went through my mind that the RN seamen officers needed to get their own logistic and refuelling act together too.”

The destroyer HMS Ursa was dispatched on January 25 to sail close to the Cocos Islands before transmitting reports of Meridian’s progress without giving away the task force’s position. She would rejoin the fleet on the 27th.

The carriers formed up on the tankers of Force 69 on January 26 and 27 to replenish their oil and aviation fuel via the line-astern method.

Lack of experience and poor training combined with outdated equipment to create a near fiasco. Tankers struggled to maintain constant course and speed. Frequently parted hoses led to seriously frayed temperes.

Victorious’ reports reveal she had used 13,500 gallons out of the 50,000 gallons of aviation fuel she carried in the first strike. Refuelling from RFA Echodale delivered 5200 gallons of aviation fuel per hour. Oil fuel was transferred at a rate of 165 tons per hour via a single hose and 290 tons per hour through a double. Time taken for the entire process was 10 hours, with hoses constantly parting at their joints.

HMS Indefatigable’s experience with Echodale was more positive. She managed to take aboard 1806 tons of fuel oil in six hours. HMS Indomitable took aboard 1815 tons of fuel oil from Empire Salvage between 08.30 and 18.30 on January 26. The delays were again caused by parted fuel hoses.

HMS Illustrious reported her marathon 12-hour session with RFA Empire Salvage to have been a station-keeping nightmare. Captain Lambe would write to his wife:

“I’ve never had a more exhausting day … (the tanker’s) speed seemed to vary constantly and the strain of avoiding the Scylla of a bump and the Charybdis of parting the hose was terrific)”

The pitifully slow refuelling rate was to have serious consequences.

Only one further strike against the oil refineries could now be completed within the required timeframe.

Admiral Vian was forced to concede any idea of a third ‘mopping up’ exercise had to be abandoned.

MERIDIAN II: SONGEI GERONG

It was expected that the Japanese would anticipate a follow-up attack on the second Palembang refinery. It was even possible details had been revealed by interrogations of downed FAA pilots.

Intelligence reports also indicated Japanese air reinforcements may have already arrived, including ‘Special Attack’ kamikaze units.

Nevertheless, the attack would go ahead.

But the plans for the Songei Gerong strike were quickly revised.

Meridian I had revealed several key flaws in planning.

Firstly, the RAMROD strikes to suppress Japanese airfields needed to be synchronised. It was obvious that attacking the airfields in succession gave sufficient warning for significant numbers of Japanese aircraft to get into the air. It was hoped smaller strikes on all main airfields at the same time would have greater success.

To this end 12 Corsairs from 1830 and 1833 Squadrons aboard HMS Illustrious and 13 from HMS Victorious’ 1834 Squadron would form two separate RAMROD forces, X-Ray (Illustrious’ Corsairs) and Yoke(Victorious’ Corsairs), which would attack the two main airfields simultaneously. They would then loiter over the airfields to engage any aircraft that later managed to get off the ground.

Secondly, the Avenger escape route and rendezvous needed to be refined. The route had proven to be more dangerous than expected, with previously unknown concentrations of AA guns. Radio discipline during the dogfights had been poor, making it difficult for the Avenger pilots to coordinate their defence. Now new radio procedures were in force, and pilots forcefully reminded of the importance of discipline. Argument still raged over whether or not the fighter pilots should break off their dogfights to more cover retreating bombers.

A new escape corridor was designated further out from Palembang city. But this extended the distance needing to be travelled before the rendezvous point was reached. The scattered Avengers, therefore, would be vulnerable longer. Covering fighters would be spread even more thinly, but it was hoped improved radio and formation discipline would make up for this. Also, the 10 Fireflies would now operate solely as close escort. Their ‘pathfinder’ and ‘flak suppression’ role was dropped.

Added to the already tight fighter equation was the perceived need for a stronger CAP over the fleet. And Admiral Vian was undoubtedly still angry about the performance of his Seafires. Four Hellcats from HMS Indomitable and four Corsairs from each of Illustrious and Victorious were retained to supplement the defensive fighter force.

In all 127 aircraft would be sent against Songei Gerong.

Lieutenant (A) Eric S.Rickman RNVR in 'My Palembang'.

Three days later Admiral Vian came aboard to talk to us. He said that Pladjoe had been extensively damaged, and was considered out of action. That left the adjoining refinery, Soenie Gerong, which we were to attack each dawn, until that too was destroyed. Our squadron target there would be the pumping house, which brought up the oil, a pinpoint target the size of an average house.

In order to obtain better photographic evidence of the coming attack, our Senior Observer, Lieutenant Ed Jess, had an opening made in port side of his Avenger, fitted with a makeshift safety belt, so that he could lean out immediately after the attack to photograph the result. I never saw the photographs, but they may well have contributed to the final evaluation. Later, our CO, Lieutenant Commander Charles Mainprice, briefed us. Calmly he said:

I have to tell you that I consider this to be a suicide mission. I asked the Admiral to send the fighters in first to shoot down the balloons, but he refused, because it would tell the Japs we were coming. I believe they will know that anyway, since it’s the only worthwhile target in the area. He also suggested that we might bomb from above balloon height, but I believe that would result in inaccurate bombing, so I said that 854 would follow its normal procedure and dive vertically, releasing at 1,000 feet. The number of aircraft needed for this strike means that five of us who flew on the Pladjoe job will have to fly again. Naturally I shall go, as will the Senior Pilot, and I would like Lieutenant Davies, and Sub Lieutenants Rickman and Twemlow to fly as well. Finally, I consider this strike to be so dangerous that if anyone would prefer not to fly, I shall respect his wishes, and shall not, repeat not, think any the less of him for so doing.

I could hardly believe my ears. Nobody spoke.

‘Right, thank you, gentlemen,’ said the CO. ‘Tomorrow morning then.’

Corsairs being ranged on HMS VICTORIOUS' deck.

“Since early that morning at 6.10 am, I had been sitting strapped into the cockpit of my Hellcat, among thirty other aircraft ranged on the flight deck, expecting to be flown off at any moment. Then the postponement had been announced over the Tannoy, for which I was exceedingly grateful because the weather was foul and entirely unsuitable as an air space in which to form up some 120 aircraft from the four Carriers. And I was still there, half an hour later, in my by now familiar state of personal twitch about whether the Admiral intended to send us off regardless or would he, as I hoped, wait for better conditions.”

JANUARY 29

At 06.00 Task Force 63 was again at Position TA with aircraft ranged on all four carrier’s decks. The weather, however, was not amenable. Heavy rainstorms extended along a belt some 30 miles off the coast of Sumatra.

But then the Barisan mountains came into view. They appeared cloud free.

The strike’s launch was delayed until 06.40, when the carriers entered the supposedly clear air between two rain storms.

An Avenger takes off from what appears to be HMS VICTORIOUS. The roundels on the wings have obviously been hastily painted-over to make them conform to Eastern Fleet standards.

“With a full range of aircraft there was a much shorter length of deck, but my take-off had been no problem because, with Indomitable thumping along at full speed, there had been plenty of wind over her flight deck. Now, fully airborne and the wheels up, was the time to peer through the murky weather, semi-dark and low clouds to see whereabouts all the other aircraft might be. In particular, I needed to start a circuit to the left looking for my Hellcat leader who, in turn, would be aiming for the group rendezvous area at 1,500 ft. So long as everyone remembered the procedure and could see to follow the Hellcat immediately ahead, all should be well.”

LAUNCH

The strike force was formed about a core of 48 Avengers, 12 from each fleet carrier. Air Coordinator Ronnie Hay and his flight would form part of the close cover fighter force.

Strike force: 12 Avengers, 12 Avengers, 12, Avengers, 12 Avengers.

Bow cover: 10 Fireflies of (HMS Indefatigable)

Close cover: 12 Corsairs of 1836 Squadron (HMS Victorious)

Top Cover: 12 Corsairs of 1830 and 1833 Squadrons (HMS Illustrious)

Mid Cover: 16 Hellcats of 1839 and 1844 Squadrons (HMS Indomitable)

RAMROD X-Ray: 13 Corsairs of 1834 Squadron (HMS Victorious)

RAMROD Yoke: 12 Corsairs of 1830 and 1833 Squadrons (HMS Illustrious)

Reconnaissance group: Two PR Hellcats (Indomitable) and two Fireflies (Indefatigable).

Air Sea Rescue: Walruses ‘Darby’ and ‘Joan’ (Illustrious)

Again several aircraft were found to be unserviceable at the last minute. The strike force was short three Avengers and one Firely.

This would rapidly get worse.

One Avenger from HMS Indomitable ditched with engine failure shortly after takeoff. Another experienced an oil leak and had to make an emergency landing. Another two experienced similar problems.

Major Hay commented dryly:

“It seemed a little early in the day to start losing aircraft.”

This left just 41 Avengers in the strike force.

Form-up was completed by 07.34 amid poor visibility – just four minutes later than the original planned time. Air Coordinator Hay, however, felt things could have gone even better, blaming the Avenger Wing commander of making an unnecessary circuit that threw the fighter escort into confusion.

The second range, made up of the RAMROD Corsairs, bow-cover Fireflies and PR Hellcats, followed shortly after. Two Corsairs were forced to turn back with engine troubles.

This time the Fireflies were able to take up their positions ahead of the Avengers before crossing the Sumatran coast at 07.52. The RAMROD Corsairs surged ahead.

Lieutenant (A) Eric S.Rickman RNVR in 'My Palembang'.

I took off in JZ240 as part of the strike. In tight formation, we approached Soenie Gerong at 12,000 feet. The CO called, ‘Line astern ... go!’ We dropped back to 100-yard intervals. I heard my gunner’s Browning start chattering, then stop.

‘There’s an Oscar on our tail!’ Vick said, ‘but my gun’s jammed.’

‘Never mind,’ I replied, ‘I’m going down now.’

As I put the Avenger into a vertical dive I could see three Avengers ahead of me, then the balloons, and, below them, yes, there it was, the pump-house! Between us and our target I could see a balloon cable, and I thought Charlie would go round it, but he didn’t. To my horror he hit it, shearing off most of his port wing, like a hot knife through butter, then going into a vicious one-wing spin, and blowing up on impact seconds later. The second Avenger rounded the cable and made its attack, then next, just ahead of me, was Roland Armstrong. I couldn’t believe my eyes when he hit the same cable as the CO, with exactly the same result. I felt sick and angry, why the hell didn’t they see that cable?

I jerked myself back to reality, time to bomb! I jinked round the damn cable, pressed the bomb-button, and, at about 300mph, started to pull out, only to find myself facing a huge rising smoke-cloud, black with jagged gouts of flame billowing up right ahead. Realising that I couldn’t do anything else, I went straight into it. It seemed a good idea at the time, might avoid flak, but the turbulence was so violent that the stick was whipped out of my hand, and the seven-ton Avenger was tossed around like a cork. All my navigator’s equipment was sent flying around, a wet accumulator had fallen over and its acid had nearly reached the aircraft’s self-destruct device.

When we emerged from the smoke, on our side at 500 feet, I grabbed the stick, went down to treetop height, and headed for the coast, blasting away with my front guns at anything worth firing at. I had just started to climb when I spotted another Avenger, away down to starboard; it seemed OK, wasn’t trailing smoke, but I realized it was in a shallow dive, and it blew up as it hit the sea. I reached down for my water-bottle (full of lime juice) that I always had in the cockpit, but it wasn’t there. I’d used it on our way to the target, so it must have shot out past me in the black turbulence of the smokecloud.

Aircraft are seen silhouetted against the clouds as they 'form up' while a Corsair begins its take-off run from HMS ILLUSTRIOUS.

RAMROD

RAMRODS X-Ray and Yoke arrived over Lembak and Talengbetoetoe airfields at 08.30, a full 15 minutes before the Avengers were due to initiate the attack on the Songei Gerong refinery.

It was immediately evident they were too late.

Both airfields were virtually empty.

Three fighters, believed to be Ki-44 Tojos, were seen on the ground along with one unidentified twin-engine machine. These were quickly destroyed.

Two other aircraft were seen struggling to get airborne. The Corsairs quickly shot them down.

After Meridian I the Japanese had established a standing fighter patrol over the Palembang district and enhanced their early-warning arrangements.

Their fighters had been scrambled shortly after the FAA strike force had crossed the coast.

RAMROD Yoke (1834 Squadron from HMS Victorious) hit its airfield at 08.28. It encountered intense defensive gunfire. One Corsair was hit in its oil tank. Struggling towards the fleet with his wingman, the pilot diverted towards designated rescue position Euston, supposedly patrolled by the submarine HMS Tantalus. But he was forced to ditch when his engine seized some 25 miles out. Lieutenant Derno was seen to get into his dinghy before his wingman frantically attempted to alert the submarine (which had actually departed the zone not knowing there was a second strike scheduled). With minimal fuel remaining, the wingman (Sub Lieutenant Davis) was bounced by a Tojo and flew through a tree while evading. Davis made it back to Victorious, where he sprinted to the island to alert them to his leader’s plight. HMS Tantalus, ordered back to the rescue zone, failed to find Durno.

An attempt was made to emulate the success of using a half-filled drop tank as a weapon in Meridian II. This time one was dropped on what was believed to be an airfield’s officer’s mess. But it failed to ignite.

This reconnaisance photo taken from Major Hay's Corsair shows bombs bursting within Songei Gerong refinery during Operation Meridian II. A tanker is burning in the river, middle-right.

“The Japanese had been better prepared, this time, so that a squadron of their fighters had been waiting for us at some 20,000 ft on the other side of the mountains and over the plains before reaching Palembang. The Corsairs above us went for the Japanese and dispersed them quickly, shooting several down, so that there was no need for us to break formation away from the Avengers. But the main Japanese fighter force was concentrated over the target area of the refinery.”

APPROACH

The main body of the strike force encountered a cloud layer just above its cruising height after crossing the Barisan mountains. This made it difficult for the top cover Corsairs to spot any approaching enemy aircraft.

Air Coordinator Major Hay was aware the RAMRODS had found few aircraft on the ground. He knew the fighter fight was going to be tough. Fortunately, the RAMROD strikes of Meridian I had seriously depleted the number of fighters available to the Japanese to counter the follow-up strike.

The Songei Gerong refinery was sighted at 08.40.

The nearby Pladjoe plant had stopped burning. But its balloons were still flying.

The Avengers broke away in a ‘step aside’ formation procedure to activate their planned regular interval, different angle, attacks. Songei Gerong was a more compact refinery, with its individual elements harder to identify and target.

Fleet Air Arm Avengers carried four 500lb bombs in each of the Meridian raids.

The Japanese again released their barrage balloons.

Once again, the Avenger flight leader redirected his Fireflies to shoot them down.