OVERVIEW

The Japanese Navy had a suite of radar and radio receiver equipped planes that could home on the unique electronic signature of USN Carrier fighter direction, IFF, radio beacons plus one demonstrated instance of Home on Jam with USS Wisconsin in March 1945.

The USN identified in its battle reports there were radar equipped Japanese control planes, which I refer to as "pathfinders," in addition to the night time radar snoopers shadowing the fleet.

These Pathfinder planes often used window (chaff in modern terms) against fighter director ships and in one case completely neutralized a fighter director ship's radar coverage prior to sinking it (USS Bush).

Some of these pathfinders seemed well piloted enough to play "fade chart games" to penetrate carrier fighter director sensor coverage for strikes against electronically "well fingerprinted" ships AKA Night Carriers. This seems to have happened to USS Saratoga at Iwo Jima and USS Enterprise during the Okinawa campaign.

These pathfinders were either supported by or displaced by land-based signals intelligence and radar during the Okinawa campaign that exploited horrid US Navy operational Security (OPSEC.)

To understand what these pathfinder brought to the table for Okinawa, the standard English text on Kamikaze operations in WW2, "THE DIVINE WIND," gives the following basics WRT command and control loops:

In the Philippines, Kamikaze doctrine had search planes sent out to spot enemy warships or task forces. They'd radio their findings to shore, from which they'd be relayed via telephone to the operations rooms at an appropriate special attack airbase. This reconnisiance cycle usually took about two hours.

By the time the Special Attack (Tokko) base commanders had formulated a plan, briefed the pilots and readied the planes, another two hours would have elapsed; so in total the delta between a spotting and launching of a Tokko mission was four hours.

The Tokko airbases kept track of the progress of the mission through routine radio reports from the aircraft in the air; e.g. "I have sighted an enemy ship", etc.

Ki-46 Type 100 “Dinah” command and reconnaissance aircraft.

DOCTRINE DETAILED

I've gone into the USN ULTRA histories for Mobile Radio Intelligence Units and found two sections that recorded the Japanese transmissions I think were associated with the May 4, 1945 attack on HMS Formidable. This is from SRH-309 part 2 pages 221 & 222. I have attached this full SRH document.

COMTASKGRP 58.3

USS Enterprise mobile R I U

4 May, 1945

Radio Intelligence Summary

Lt(jg) R. B. PalmerPHASE 3

This concludes the attacks against Okinawa shipping. In the meantime Formosa planes had not been inactive and at 0616 a search plane (3EKA) was being called by Shinchiku. This recco plane was finally heard at 0828 when he sighted enemy carriers in the position 2347N-12423E. Ot 0837 another recco plane (0SESU) came up on the Formosa tactical circuit and reported carriers in the position 2342N-1251E. This was followed by weather informtion from both planes and at 0844 3EKA saw 5 carriers in the position mentioned above. 0SESU saw 4 carriers and 10 additional ships and gave the base the information as to what altitude the enemy CAP was flying.

At 0955 attack planes were on their way and from the calls heard on the curcuit 3 groups were involved. Roughtly this meant at least 35 planes took part in the attack. At 1046 the controlling base, probably Shinchiku, told a coordinator that one wave of suiciders had left Giran at 0950 and another at 1010. At 1120 the 46th wave had left.

At 1222 a third snooper 0SCNE, sighted a force containing 4 cruisers and 8 DDs in the position 2422N-12533E.

Finally at 1230 the base came up and told the attack units in plain language to change the attack ara to the position 2342N-12533E or the approximate position of the carrier forces. This was followed by another plain language message at 1300 saying the enemy was 60 miles south of Liyako Jima. The activity on this circuit died down at 1430.

My broad outline analysis of IJN C3I doctrine at Okinawa and its strategic effect on Operation Olympic -

Okinawa naval garrison commander Adm Ota's land-based radars were popping up and taking snapshots of the CAP array and providing radio beacons for the "Kyushu to Okinawa" and "Kyushu to Okinawa" aerial highways. (The former was in Kume Jima and the latter was in Naha.) These CAP "Snap shot" reports were sent by undersea cable to Kyushu and Formosa.

The Radar Snoopers were sent from Kyushu, briefed with this information, to scout the American carrier fleet and provide targets.

The pathfinders were sent out after the snoopers, but before the Tokko aerial waves. It listened to the snoopers and herded the tokko waves around the CAP and into the pickets, as well as provided updates to succeeding Tokko waves. Early on, the pathfinder's went after the American fast carrier fleet, as Ota's targeting sufficed for the pickets.

As the campaign developed, the pathfinders herded the Tokko waves into and over Ie Shima.

The Tokko used Ie Shima as a radar shield to get into the inner screen and transport area between Ie Shima and Okinawa's Hagushi beach anchorage. This area was so filled with US Navy warships, landing ships, landing craft, transport and freighters that American day and night fighters could not engage for fear of the trigger happy naval gunners.

The losses to the naval gunners were less than the fighters.

When the US Navy added a radio mobile intercept team to Adm Turner's AGC EL DORADO in late April, early May 1945, it unwound this pattern and from the relative lack of Okinawa to Kyushu message traffic figured that the Naha undersea cable was an important piece of the Kamikaze campaign.

This lead to changes in picket disposition, the placing of Radar's on Tori Shima and the plan for the 6th Marine Division to take Naha.

The US Navy used UDT teams to destroy the underwater cables off shore of Naha and battleship heavy guns to tear up Naha's underground telephone cables to make them useless.

The only records of these actions during this invasion are in the written US Army's Signals Corps reports that complained in writing as they were going to use those cables to get around Japanese irregulars.

Without Ota's snapshot reports, with B-29's bombing the heck out of Kyushu air bases, and with Turner having his own Sigint, the radar snoopers and pathfinders were less effective and the IJA lost heart in supporting further Okinawa Tokko operations.

The full weight of American material was now being applied on the right Japanese targets at the right time as the Japanese were no longer inside the American OODA loop.

However, the Imperial Japanese still scored a significant campaign victory in that Adm Nimitz lost his nerve to take Kikia Jima, the forward air base he promised to MacArthur and Kenney for Operation Olympic. The base Kenney's P-47 fighters so desperately needed to cover the proposed Kyushu landings.

The US Navy had a lot of other issues with intelligence losses that contributed to this situation, which is the subject of the next rock.

Fleet Air Arm Avengers fly over HMS King George V and the British Pacific Fleet.

PINPOINTING THE BPF

Regarding USN intelligence versus the Japanese rock, I'll start first by explaining how I think HMS Formidable got tagged by Japanese C3I.

We know from David Hobb's "The British Pacific Fleet: The Royal Navy's Most Powerful Strike Force" that the RN was well aware of the IJN's radar pathfinder plane tactics. Calling them "Gestapo planes" because they thought they were "minders" there to report on the personal performance of each Kamikaze for possible secret police retribution against Kamikaze pilot families.

What the RN didn't know about was the interaction of Allied IFF, Japanese land based naval units particularly regards radar, SIGINT & undersea cable communications due to USN intelligence failures, both organizational & leadership driven.

To begin with, there were not that many Japanese Kamikaze sorties actually coming from the Sakishima chain. There were a total of 30 in the entire Okinawa campaign. The following is from the Kaimikaze Images web site. The US academic who has maintained it since 2003 just got his PhD and he made the Kamikaze phenomenon the meat of his study. He has Japanese language skills and visited dozens of Kamikaze shrines and transcribed the information on them into many of his posts.

This is from one of his book reviews:

Wings Over Sakishima

by Fredio Samples

Privately published, 2010, 157 pagesHowever, the book provides no information on specific flights flown from these two islands. For example, no mention is made of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps 3rd Ryūko Squadron that made sorties from Miyakojima in late July 1945 and sank the destroyer Callaghan (DD-792) (see web page on 3rd Ryuko Squadron Monument). Among those men in the Japanese Navy who died in aerial suicide attacks, 23 made sorties from Ishigakijima and 7 came from Miyakojima [1].

And this is his 3rd Ryuko Squadron Monument link [3]:

Whether the small number of sorties was due to the USN/RN bombing campaign or a lack of Japanese logistics in the first place is an open question.

These are the May 4, 1945, pages, 57 & 58, of this document: SRH-257 ANALYSIS OF JAPANESE AIR OPERATIONS DURING OKINAWA CAMPAIGN, October 1, 1945

The following is from SRH-309 Part One pages 165 & 166. It has far less information than Lt(jg) Palmer's team, but it had a Banzai call to a base on the Formosa channel that could have been attacking a Royal Navy ship.

COMTASKGRP 58.4

USS YORKTOWN CV-10

Report of R I U activity for the period of 1 May 1945 to 7 May 1945, inclusive.

Lt. (jg) W.M. Kluss4 May, 1945:

This force East of Okinawa, for Okinawa support and Kikaishima patrol. Position at 1100: 26-45N 129-51E.

Morning activity developed slowly at first, with what appears to be one search plane, on 3421J, a routine bombing raid on 3320J involving three plane calls, and sporadic splurges of activity on 6650J. By 0045 through, four plane calls show on 3421J; one a search plane of last evening. An “ETA in the battle area” is sent by three of these planes on 3421J, an hour and a half in advance of their expected arrival. An ETA of this sort proves to be one of our most valuable intercepts.

The one search plane on here seems to search on a line about 200 miles East of the Okinawa group of islands, so it is not known how the attack planes sized up our forces. This was probably done by radar, as the forces that were attacked were about 50 miles from land, according to positions given by the attacking units. The attack comes off about on schedule, at 0245, with a T-TOTO from on unit, immediately followed by the other two units at 0249 and 0395.

What appears to be two new search planes appear on 3421J at 0225 and 0312, and seem to reach our force at about 0345, as we get bogeys on our radar and start shooting down Bettys at this time. one splashed at 0345, one at 0420, and one on fire at 0448. Reaction to this was a TUSEU from one of these search planes on 3421J at 0417, a half finished message at 0448, and another half-finished message at 0522, marking the disappearance of these planes from the circuit. our force was not sighted, judging from the reaction.

An Emily is splashed by our VHF at 0154, just 19 miles away. No reaction was noted for this.

Activity developing on 6650J, involves ten plane calls, variously appearing by 0138. First signs of their contact is a HIHIHI at 0325. This is followed by a TOTOTO at 0354, by the same unit. Another TOTOTO shows at 0401, by another unit. This is the only warning of the attack that is noted here In fact these are hardly warnings. The only warning, whould possibly coe from a judge of the proximity of the planes, by their signal strengths.

We are unable to give very clsoe attention to what seemed to be a bombing raid heading for Okinawa, on 3320J, but what coverage we did give it showed no developments by 0600.

Three search planes apepar to be homing on 5852A, at 0643. These have not previously appeared on 3421J.

The Formosan frequency, 5290A, seems to be used for homing between 0534 and 0600.

Renewed activity shows on 6842J at 0608. We go to GQ at 0818. Attacks turn out to be on the forces near the beach. Reaction shows on 6948M at 0834, and on 6842J at 0843. One flight involving possibly 4 planes showed on 6948M; on of these giving out a “Banzai” at 0834. When the base asks for a repeat on this, the plane sends SETA (repeated) HE (repeated), then a long dash as he apparently goes into his dive.

The activity on 6842J seems to involve 3 units, or flights, sending attack signals almost continuously between 0843 and 0914, saying also, in both code and plain language, the results of the attack.

Air activity shows during the rest of the day on 6580J, 6650J, 6948M, and 5852A, but does not prove of any tactical value to us.

I photo captured all the May 4, 1945 IJN aerial operation sections from the following document:

Japanese Monograph No. 83 Okinawa Area Naval Operations

Compiled 8 May 1948

Welfare Ministry Demobilization Bureau,

Second Demobilization Bureau

Liquidation Department

The PDF is 66 MB over at this web site:

Annexed Table No 3

The Role of Special Attack Planes in the Okinawa Area Operation

A. The Tenth Air Attack Force (5th Air Fleet, 3rd Air Fleet, and 10 Air Fleet)

Operation of Tenth Air Fleet Excluding Special Operations

Third, Fifth & Tenth Air Fleets Excluding Special Operations

A kamikaze, fuel tanks ablaze, plunges into the ocean amid a US task force.

HEAD SHOTS

I've been systematically pulling every primary source I can on the Okinawa campaign since ~2013 because the narrative stories just made no sense to me.

I eventually started to piece together IJN/IJA radar and sigint capabilities and asked myself how I would use them. Then I looked at USN war diaries and USSBS interviews to assemble clues as to what Japanese tactics & doctrine actually were using those radar and sigint capabilities as opposed to post-war USN narrative.

One of the things that popped out was that the Japanese were systematically targeting USN command ships and fighter direction platforms the last year of the war.

Look at the Com5th Fleet command ship list.

Adm. Spruance's flagship's were attacked three times in the Operation Iceberg campaign.

The USS Indianapolis was struck by a kamikaze and hunted by another at the Kerama Retto anchorage the next night before he moved his flag to the USS New Mexico.

The USS New Mexico was specifically targeted May 12, 1945. This is the letter Adm. Spruance wrote about it:

Admiral Spruance Recounts Kamikaze Attack on His Flagship, New Mexico (BB-40)

COMTASKFORCE58, Adm. Mitscher had the USS Bunker Hill and USS Enterprise shot out from under him as flagships. The RN Observer with Lt Sims radio intelligence team got two seperate kamikaze attacks to write the Admiralty about.

This is why the Japanese prioritized hitting Adm Spruance's various flagships at Okinawa (and Adm. Mitscher's flagships as well).

In March, a FRUPAC unit assigned to the USS Indianapolis, then being used as the flagship of the 5th Fleet commander, Admiral Raymond Spruance, participated in the invasion of the Kerama Islands, a group of small islands about 30 km southwest of Okinawa, which was needed as a base to support US military forces in the lead-up to the invasion of Okinawa itself.59 In late March, the Indianapolis began operations just off the Okinawa shore, moving backwards and forwards along the coast, bombarding the island while the FRUPAC unit monitored radio communications concerning attacks on the fleet by kamikaze pilots. When the Indianapolis was badly damaged in a kamikaze attack on 31 March, Admiral Spruance moved his flag to the old battleship USS New Mexico, with the FRUPAC task force group moving with him, continuing its communications interception activities. The New Mexico was hit by a kamikaze aircraft and severely damaged on 12 May 1945. The radio shack was destroyed, one of the FRUPAC members, Walter Rougeux, was killed, and nearly all the others in the shack were wounded. Rougeux is believed to be the only member of FRUPAC to lose his life in action during the Pacific War. Before it was knocked out of action, the unit ‘had [from our intercepts] been able to inform the fleet that kamikazes were headed our way’.

A member of the FRUPAC unit which served aboard the USS Indianapolis and the USS New Mexico at this time has written that:

Probably at no time during the war was a task force group assigned to a flag at sea able to furnish tactical intelligence of more value to the fleet than during those days around Okinawa. By intercepting messages to and from kamikazes, sent in either plain language or simple code, my group was able to warn ships in the area well ahead of the time to be especially alert and prepare for attack because kamikazes had departed their bases and were enroute to the Okinawa area. Usually the warning could give an indication of how many planes to expect, and even their estimated time of arrival over the fleet. Then a warning that an attack was imminent was flashed to the fleet when we intercepted that final in-the-clear “Banzai” (Japanese cheer of triumph sent by kamikaze pilots just before diving to their death).61

In July 1945, after Okinawa had been captured, the NSG set up a radio interception and DF station in Quonset huts, near the small town of Aragusuku, in a field of rice paddies and sweet potatoes, about two km inland from Sobe. It had an initial complement of five men, with Richard S. Katzenberger in charge. It was called a Naval Supplementary Radio Station until January 1947, when it was renamed Communications Support Activity No. 3256. It remained at Aragusuku until November 1949.

Gunners aboard USS Essex engage a B6N torpedo bomber.

The Imperial Japanese Navy garrison on Okinawa had a sigint teams, minimally, at Naha, Miyoko Jima and Amami Shima. The two admiral's Mobile Radio Intelligence Teams were broadcasting warning to USN planes and combattants in the clear or using 'shackle code' in front of Japanese signals intelligence and direction finding teams.

I've spent the last couple of years piecing together the "USN command ship victim list," which is attached.

I haven't added British Pacific Fleet vessels that meet the criteria of the attached list, as I don't know which ships were flag ship, task group fighter director or radar pickets.

(ArmouredCarriers: HMS King George V was flagship Vice Admiral Bernard Rawlings, HMS Indomitable was flagship Rear Admiral Aircraft Carriers Philip Vian.)

RADAR ABSTRACT

Vol. 1, No.51

NLO Radiation Laboratory, MIT

17 July 1945INSTRUCTIONS TO JAP SUICIDE: PILOTS REVEAL HOW PLANES APPROACH IN AREAS NOT COVERED BY RADAR

(Hq. AAF Intel. Summary, 45-12)

How the Japs have shaped their tactics for single suicide planes attacking our shipping to take advantage of areas not covered by our ship-borne radar is clearly disclosed in instructions in a training manual recovered recently from a crashed Kamikaze plane.

Pilots have been encouraged to use three types of approaches to our fleet, and all of them are out of the realm of radar coverage furnished by systems now installed in our ships. Choice of the three depends,, it was explained, on weather conditions, cloud coverage and the degree of darkness.

Diagrams of the tactics indicate that zenith coverage, such as is provided by Radiation Lab's SO-11, is needed as badly as any to fill the gaps being used by the Japs.

In the steep diving approach, the first described in the pilot's instructions (see diagram) , the initial dive was to begin above 19,200 feet at a speed corrected to about 200 miles per hour.

When the suicide plane had gone down to 6,400 feet, the final run into the target was to be started at a speed of 200 miles per hour with an angle of dive between 20 and 40 degrees.

The suicide planes were to hit the target at a speed of about 280 miles an hour. During the final run from 6,400 feet, the pilot was told to be sure not to overaccelerate the plane so that its maneuverability would be retained.

A somewhat more horizontal approach is provided in the second method, with a dive of between 32 and 35 degrees beginning approximately 2,100 yards out from the target at an altitude of about 5,000 feet. When an altitude of about 2,000 feet was reached, the dive angle was to be decreased to 25 degrees.

The dive angle was to be cut to 10 degrees at 500 feet and this was to be maintained until the plane hit the target at a final speed of about 280 mph.

"Horizontal collision" is the name given to the third type of approach. From a point approximately 3,200 yards out from the target and at an altitude of about 4,000 feet, a dive of 25 degrees was to be started at a speed of 185 mph.

When the suicide plane was about 750 yards from the target and at an altitude of about 60 feet, the "final suicide run" in a dive of about 10 degrees was to be started. The final collision speed was to be about 250 mph.

Final instructions on aiming points warned the pilot that "it is essential at this time not to miss the target because of shutting one's eyes for a moment."

US forces assemble at Ulithi, prior to the Okinawa campaign.

INTELLIGENCE OPERATIONS

The USN did not have a good handle on what the radius of action of a Kamikaze converted plane with one or more drop tanks was/were. This gave the Japanese a lot of room to run radio deceptions on the USN indicating more flights from Formosa than were actually happening.

I have the relevant Ultra histories covering the USN radio intelligence units with the US Fleet during the Iwo Jima & Okinawa campaigns. These are SRH-289 and SRH-309 parts 1, 2, & 3.

It turns out there were RN sigint observers with the RIU's in both campaigns. See these photo clips:

The yellow highlighted islands (below) hosted air fields that staged both daytime Kamikaze planes and night time radar planes throughout the Okinawa campaign. The top right bases were on the Kyushu to Okinawa radio navigation route while those at the lower left were the Formosa to Okinawa. Both operational patterns were spotted by USN Picket Destroyers and Amphibious Command ships in the middle of May 1945.

This is a map with Ryukyus air bases is adapted from Robin Reilly's Kamikaze Attacks of WW2.

This is a modern map with the locations of all the IJN radar during and after the Okinawa Campaign.

In short, the Japanese had heavily infested the islands north and south of Okinawa with land based radars. These radar stations all had radios and some were situated on islands near land stations for undersea telephone/telegraph cables. So they could pass on their observations without any chance of radio interception.

This is a map of the IJA radars in the Ryukyus from Japanese archives.

CLICK TO EXPAND: This is a photo capture of my Ryukyus radar site spreadsheet.

RADAR OPERATIONS

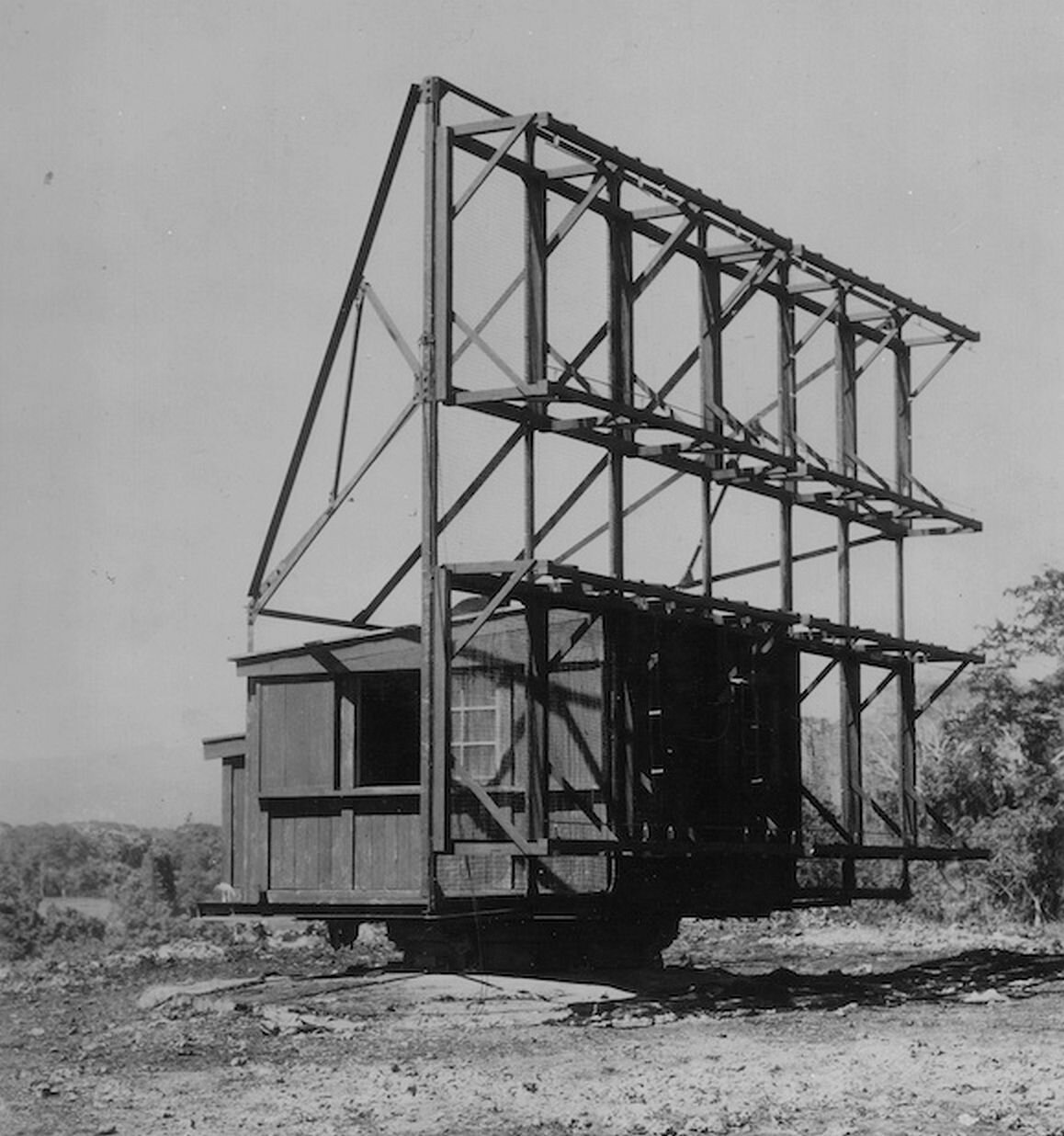

Now we look at the Type 11K IJN long range land-based radar.

It's operating frequencies sat within the set of frequencies that Allied Mark III identification friend or foe system operated, 157-187 Mhz. According to the post-war FEAF document series "A Short Survey of Japanese Radars" one of these radar sets was stationed upon the island that Task Force 57’s battleships were busy bombarding May 4, 1945. It could see the CAP over the UK battleships and the CAP over HMS Formidable at 15,000 feet up to 300km away.

This by itself would not have been enough to hurt the British Pacific Fleet's carriers as IJN radars need to be associated with radio-intercept units and telecommunications to be useful for targeting the Kamikazes. It turns out Adm Ota had some really nice hold out cards to do just that.

Naha was the location of one of the IJA's major pre-war high frequency sigint facilities aimed at Siberia and Soviet maritime provinces, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

The land-based radars used in the Ryukyus can be found in the following Japanese documents:

JACAR C08030143900 The 4th Escort Fleet, Okinawa Area Base Force Unit Wartime Diary under Adm Midoro OTA.

Per Senshi Sosho Vol. 17, the command structure of the Navy radar warning system on Okinawa under Adm. Ota was as follows.

Okinawa Area Base Force Commander

Ohshima Guard Unit Commander (Amami-O-Shima Area)

Special Lookout (AKA RADAR) Stations on: Kuchinoerabu Jima, Takara Jima, Okinoerabu Jima

The 43rd Minesweeper Division Commander (Okinawa Area)

Special Lookout Stations: Kume Jima, Miyako Jima, Ishigaki Jima, Yonakuni Jima

RADM Ota Minoru was the Okinawa base force commander during Operation Iceberg and was dual hatted as the 4th Escort Fleet commander. This gave him a lot of scope of action to prepare to defend Okinawa.

Judging from the information I've found in the wartime MIT "RCM Digest #19" RADM Ota was a "Black Swan" in that he seems to have been a technological warrior in the class of German General Josef Kammhuber or more recent Serbian Colonel Dani Zoltan, (his SA-3 battery shot down a F-117 over Kosovo in 1999).

Even more interesting, he also cared enough for things outside himself and his faction that he put beating Japan's foreign enemies ahead of the rivalry with the Imperial Japanese Army. This fact was important for the HMS Formidable story.

Ota Minoru

The following is from the 1953 Japanese Monograph No. 118 "Operational History of Naval Communications Dec 1941 - Aug 1945," published by Military History Section, Headquarters, Army Forces Far East on the radio intercept teams deployed by the IJN in 1944 to stop the bleeding out of their merchant shipping from USN submarine attacks:

From March 1944, foreign communications interception teams each consisting of one petty officer and three teams, were assigned to flagships in important convoys and also to escort aircraft carriers for the purpose of avoiding enemy submarines and detecting enemy patrol planes. Moreover, the 1st Surface Escort Unit headquarters was reinforced with six teams and each 'naval district, (except Maizuru) .. and each guard district with two to six teams respectively. These teams achieved considerable results but the commanders could not utilize them to the fullest extent because the ships lacked high frequency radio direction finders.

Ota as both Okinawa Area Base Force Commander and 4th Escort Surface Unit commander had somewhere between four and eight of these sigint teams.

The most likely places for four of these sigint teams under Ota were on Okinawa at Naha, Amami-O-Shima to the north, and both Miyako Jima, Ishigaki Jima to the south of Okinawa as all four locations were sitting on the undersea cable retransmission stations between Kyushu and Formosa.

General Ushijima and Adm Ota were in charge of the IJA & IJN garrisons on these islands respectively. They made an agreement to share radars and radar crews. Both IJN & IJA radar operated under one tactical doctrine and probably Adm Ota's operational command during the Okinawa campaign.

Short form:

Ota had systematic and complete air coverage of Allied air movements from Formosa to Kyushu when he wanted it and a secure means of passing that information to IJN 1st Air Fleet on Kyushu until the US Marines overran the port of Naha in June 1945.

HMS Formidable was victimized by this C3I system at Miyako Jima.

Ota Minoru

This is Ota Minoru’s C.V. pulled from Section 22 list members and various Japanese scholars:

RADM Ota Minoru was in the late phases of the Rabaul campaign when Gen Kenney was making mass air strikes through the IJN's first land based early warning radar network and Section 22 was making itself felt as a ELINT -- electronic intelligence -- organization in plotting the gaps in that screen to allow the shorted warning time to Rabaul's air defenses.

This is RADM Ota Minoru career track until his death at Okinawa:

Ota Minoru

Eta Jima Class 41 (64th of 118)

BORN - 7 April 1891, Chiba Prefecture

Promoted Midshipman - 19 December 1913

Promoted Ensign - 1 December 1914

Equipping Officer, Fuso - 27 October 1915 - 8 November 1915

Crew, Fuso - 8 November 1915 - 1 December 1916

Promoted Lieutenant (j.g.) - 1 December 1916

Acting Division Officer, Sasebo Sailor Corps - 1 December 1919 - 1 December 1920

Promoted Lieutenant - 1 December 1920

Division Officer, Hiei - 1 December 1921 - 13 August 1923

Division Officer, Fuso - 13 August 1923 - 1 December 1924

Promoted Lieutenant Commander - 1 December 1926

Division Officer, Yokosuka Sailor Corps - 1 November 1929 - 1 June 1930

Chief Gunnery Officer, Yokosuka Sailor Corps - 1 June 1930 - 2 November 1931

Promoted Commander - 1 December 1932

Executive Officer, Yamashiro - 1 December 1936 - 16 October 1937

Commanding Officer, Tsurumi - 16 October 1937 - 10 August 1938

Promoted Captain - 1 December 1937

Commanding Officer, 6th Kure Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) - 20 January 1939 - 1 April 1939

Executive Officer, Kure Sailor Corps - 15 April 1939 - 1 November 1941

2nd Cmb SNLF Commander 01 May 1942

Promoted Rear Admiral - 1 November 1942

[He commanded the 2nd Cmb SNLF for only a short period, from May 1 1942 when the unit was formed until it was disbanded on July 1 1942 since the IJN lost at Midway. On Jul 1 he was sent back to Kure and then the Sasebo 2nd Naval Corps Commander on Aug 10.]

Attached to Kure Naval District, 01 Jul 1942

Sasebo 2nd Naval Corps Commander - Aug 10, 1942

Promoted Rear Admiral - 1 November 1942

Commanding Officer, 8th Combined SNLF - Nov 20, 1942

Commanding Officer, 2nd Combined Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) - 20 November 1942 - 1 December 1943

Commanding Officer, 14th Base Force** - 1 December 1943 - 10 February 1944

[Organizational note: The 8th Combined SNLF was created on Nov 20 1942 and Ota was appointed as commander. On Dec 1 1943 the 8th Cmb SNLF was reorganized into the 14th Base Force and Ota was appointed commander. On Feb 10 1944 Ota was sent back to Japan to the IJN general staff HQ.]

Commanding Officer, Sasebo Sailor Corps*** - 10 February 1944 - 20 January 1945

Commanding Officer, 14th Base Force - 1 December 1943 - 10 February 1944

Commanding Officer, Sasebo Sailor Corps - 10 February 1944 - 20 January 1945

Commanding Officer, Okinawa Base Force - 20 January 1945 - 13 June 1945

Commanding Officer, 4th Surface Escort Division - 20 January 1945 - 28 February 1945

Killed In Action - 13 June 1945 (Age 54)

Posthumously promoted Vice Admiral - 13 June 1945

The Commander's Room of the underground Naval Headquarters on Okinawa.

Ota's Career in Context

After being commissioned, Ota passed gunnery school and torpedo school as most of other navy officers. But he was not educated in navy telecommunication school, the only place to learn about "wave weapons" AKA RADAR.

Ota Minoru was a leading figure in ground combat, taught in gunnery school. He learned more in advanced course (koto-ka) of navy gunnery school and experienced a trainer in that school.

To know precisely about his appointment in Sasebo, you have to distinguish between "keibitai" and "bobitai".

Both could be translated as 'guard force' or something, but in short, bobitai was originally coast watcher unit, placed in distant places from Chinjufu.

Keibitai was originally a navy infantry troop guarding Chinjufu.

In WWII period two unit types overlapped; AA guns, especially large-caribre ones belonged to keibitai, while bobitai maintained many local watch points. But gradually both bobitai and keibitai began to maintain radar sights. But it was keibitai CO who examine all information from radars and watchers and direct AA gun crews.

In Mar 1944 Ota was appointed to command Sasebo kaiheidan and Sasebo keibitai. Kaiheidan was a training/personel pool organization, but in emergency kaiheidan provided their men for local defense, keibitai's original duty.

As an experienced trainer in gunnery school it looked nice for him to take on both in the eyes of the navy authority.

So it is true Ota was in a position to make use of all radar information for Sasebo's responsible area, but Ota had no formal training on radar. Some densoku shikan (navy officers specialized in radar) might have helped him, but keibitai AA battle report suggests reports from radar sights to keibitai HQ provided allied aircrafts' position and number. It might be enough for Ota and knowledge about radar was not important.

Ota's knowledge of the need for radar at the Kume Jima "bobitai" was such that he actively cooperated with General Ushijima's 32nd Army radar network for months to the extent that he traded a navy radar crew for an Army radar.

This implies either Ota had radar knowledge or a trusted "densoku shikan" who convinced him that such a trade was both necessary and needful enough to require an unprecedented level of cooperation with the Japanese Army.

Ota was enough of a maverick in other respects -- his care for the Okinawan people in his last official document is but one example -- that it implies more than a passing interest in the subject of radar

INTELLIGENCE FAILURES

In trying to explain the dysfunction of the USN intelligence enterprise as related to the attack on HMS Formidable in May 1945, I've got to start like I was trying to eat an elephant...one bite at a time...and a lot of bites follow.

Off the top of my head there were three major institutional themes that dominate.

The USN did not play well with others.

The USN did not play well within and between its various intelligence bureaucracies due to the budget & power games involved.

Top to bottom, the USN had the operational security of a 5 year old.

All three issues played a role in the Okinawa campaign.

For instance, the US Navy knew a great deal about Japanese radio intelligence, radar and communications infrastructure. The Joint Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Area (JICPOA) under Admiral Nimitz' Pearl Harbor headquarters had issued a series of reports including CinCPOA 5-45 Japanese Radio Communications and Radio Intelligence, "Know Your Enemy!"; CinCPAC-CinCPOA Translations Item #9,017 "Organization and Operation of a Radar Lookout Station"; CINCPAC-CINCPOA bulletin no. 161-44-Okinawa Gunto November 1944; all detailing radars, undersea cables, and other command, control, and intelligence (C3I) facilities in the Ryukyu's island chain.

I've hammered on the IFF vs Japanese radar issue previously, so I'll point to a number of other glaring errors in these intelligence reports, particularly about the undersea cable network and radars, stemming from those three issues, which would cost the American military dearly at Okinawa.

This figure is taken from 10th Army Tentative Operation Plan No. 1-45 -- Enemy Signals Installations. The added yellow highlights are for the undersea telephone/telegraph cable and radars. JICPOA only identified on this map three radars of eight radars actually located adjacent to or on Okinawa plus it wrongly placed the cable's southern segment as landing at Hagushi beach.

A Feb 1944 US Army Civil Affairs report using what is now called "open source intelligence" correctly identified Naha as the landing point for the cable from Formosa, which JICPOA disregarded. A 1953 Pacific Science Board report, done as the US occupation of Japan was ending, also identified the Formosa to Okinawa cable as landing at Naha and that this had been true since _1913_. Okinawa Naval garrison commander Adm. Mitoro Ota's last documented use of this cable was on 6 Jun 1945. In this message he asked the Emperor to remember the sacrifices of the Okinawan people in defense of Japan. You can look it up and read it on Wikipedia.

That 10th Army commander General Buckner didn't use US Army intelligence here is likely an artifact of his being loyal to his USN CentPac patrons after Smith vs. Smith.

Now, regarding OPSEC, US Navy operational security in the last 11 months of WW2 just sucked.

Then there’s what the IJN got from USS Darter. This photo clip is from the original source, SRH-254 THE JAPANESE INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM MIS-WDGS 4 September 1945

USN opsec problems neither began, nor ended, with Darter. Halsey & McCain's pilots in TF 38 were known for horrid document security. This photo clip is also from SRH-254 THE JAPANESE INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM MIS-WDGS 4 September 1945.

TF 38 pilots In the Sept 1944 - Jan 1945 period also lost Ultra data provided to the SWPA theater which General Akin's intelligence liaison related to Halsey. According to John Prodos, the USN intelligence poohbahs went after MacArthur for that until the real source turned up in later Ultra decrypts. Opps!

You will love this OPSEC/Oppsie-SEC facepalm from John Monsarrat's history monograph on Fleet Radar versus Kamikaze's that showed:

Escorts engage a low-flying kamikaze during flight operations off Okinawa.

The American carrier groups were constantly on Inter Fighter Director channels to redirect fighters that the IJN Type 3 Air Mark VI Radar homed upon,

They were constantly pinging these fighters with SC radar's IFF to track them, and

To top it all off discussed fighter director doctrine, in combat, IN THE CLEAR.

This is a dinner bell, plus spotlight on the defending fighters, plus planting a bug in your state room for the enemy to hear, all in the first month of the Okinawa campaign.

And please carefully note that the Admiral mentioned below -- Admiral Radford -- later became Chief of Naval Operations after WW2.

John Monsarrat, Angel on the Yardarm : The Beginnings of Fleet Radar Defense and The Kamikaze Threat, Naval War College Historical Monograph No. 6, 1985 pages 162-163

It was at about this time (Trent NOTE: 2 April 1945) in the operation that Admiral Radford, commander of TG 58.4 ordered into operation an idea that must have looked good on paper on the flag bridge, but was counterproductive in CIC. He ordered all the carriers in his group to station their combat air patrols in an orbit in a YE Sector* several miles away from the group instead of directly overhead, as had always been the practice. The purpose, of course, was to get the jump on attackers that suddenly appeared on the radar at short ranges and presumably low altitudes. In practice, however, it complicated an already too-complex radar picture. As long as the CAP was "anchored" in orbit overhead, we did not have to keep track of it until we sent it out on a vector, and it in turn *YE SECTOR was one of four quadrants into which a different letter was broadcast daily in Morse Code to aid in homing lost planes.

Carriers Versus Kamkazes , 163

had an easy time keeping station in any weather other than solid overcast. But when it was ordered to take station ten miles away and to stay in tight orbit, it had no reference point to guide it; and with the whole task group continually zigzagging and frequently turning into the wind to launch or land aircraft, it is no wonder that it would frequently drift or wander off its prescribed station. Under this system, the fighter directors in the carriers that had provided the CAP were responsible for policing it, and the group FDO "policed the policemen" extremely rigidly, obviously on direct orders from the admiral. The fighter director radio network crackled with transmissions all day, herding the CAP into two- and three-mile shifts of position and responding to caustic comments from the flagship to the effect that it was again off station. This was a constant irritation to the fighters as well as to the FDOs; but that was negligible compared to the problems it created with the radar. The more cluttered with targets a radar screen became, the more difficult it was to discover and assess any new target instantly. We already had to follow too many different flights of our own planes and those of adjoining task groups. Additionally, because the station-keeping of the CAP was being watched so meticulously in the flagship, we had to assign our SC radar almost full time to keeping tabs on it, whereas this radar, along with our SK, should have been searching for the enemy. There was also a big worry in my mind that a kamikaze could sneak in at low altitude on the opposite end of the group and strike before we could get the CAP back in time to intercept.

As the days wore on, many tempers grew short over this whole issue, and I sensed that Lieutenant Commander Carl Ballinger, our group FDO in Admiral Radford's flagship, understood the difficulty but could not get the order rescinded. Sure enough, a few days later he called for an unprecedented radio conference among the senior fighter director officers in all four of the carriers in the group. He alerted us during the day and set the time of the conference for that evening after all planes had landed, explaining that he wanted each of us to be prepared to give him our reaction to the new plan. I welcomed the opportunity, and prepared my objections to it carefully and as objectively as I could. While I was perhaps the most outspoken in urging a return to the overhead station, all the others were, to some degree, in favor of it, and I think we gave Ballinger good ammunition to use with the admiral's staff. The order was not rescinded, but the over-tight monitoring of it was relaxed,

Nor was this the only example of this USN OPSEC hubris. See the C.O. of USS Bullard's comments here and note the invincible USN Flag Rank ignorance of skip-zone radio propagation for OPSEC during the Okinawa campaign:

"The security of the MAN circuit is NIL. During this operation 36.5 KCS and 33.2 Mcs were used on this equipment for inter-fighter direction. This vessel has had excellent reception from various ranges up to 1100 miles. On March 10th, when 1100 miles to the southeast, ships operating off Iwo Jima were heard distinctly. On May 10th, while operating 80 miles northeast of OKINAWA, good reception was heard over MAN with the radar picket group of Task Group 58.1 who was at the time some 600 miles to the southeast. During this operation, vessels operating off OKINAWA beaches were heard from distances of 50 to 250 miles. In spite of the poor security of this circuit, we continue to put out information of great value to the enemy. Our task groups are more vulnerable during periods of launching and landing of aircraft. Yet we broadcast the pancake time of our CAP regularly in plain language. We also make available to the enemy over this circuit valuable information on the characteristics of our search radars.

We broadcast the fact that "bogey faded on bearing 300 Degree T distance 30 miles" and follow it up with "Bogey now out of fade bearing 320 Degrees T distance 20 miles". Giving the enemy credit for having average intelligence it is not inconceivable that from this information he can prepare fade charts of our radars. During this operation it is certain that enemy planes made use of this information we so generously gave them. It is recommended that a circuit that affords greater security be used for inter-fighter director work."

Citation:

CDD96/A16-3,

Serial: 033

Commander Destroyer Division Ninty-Six

Report of Ops During carrier air strikes on Japan, Ryukus & Jap Task Force, 3/18/1945 - 5/27/1945

Page 207 - 208

Action Report USS Bullard (DD660)

Part VIII Conclusions and Recommendations

Found HERE

and HERE

BLIND SPOTS

On 11 April 1945, the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Bullard was slightly damaged by a Japanese suicide plane.

IMO after USS Darter's captured documents were analyzed by the Japanese Navy, they would have keyed off of the USN Carrier Fleet's IFD & "Fleet Common" signals for the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

We know that because that is what happened to Adm Halsey in the South China Sea in 1944 and to American Night Carriers off Iwo Jima and Okinawa in 1945.

COMMANDER THIRD FLEET

SERIAL 0087 26 JANUARY 1945

REPORT ON COMMUNICATION OPERATIONS

SEPTEMBER 1944 - JANUARY 1945

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATIONS

DURING THE THIRD FLEET OPERATIONS

IN SUPPORT OF THE PALAU, LEYTE,

AND LINGAYEN CAMPAIGNS

7. INTRA-FLEET CIRCUITS

(a) Practically no use was made of the Task Force Commanders, Task Group Commanders or Task Force Cormon frequencies as set forth in the Basic Fleet Frequency Plan. This was due to normal radio silence conditions observed and the use of the two TBS circuits and visual channels to handle all intra-fleet traffic. The Task Group Commanders frequency was used several times early in the operations period but was discontinued when it was discovered that units were accurately DF'd by the enemy. The Task Force Commanders frequency was employed as a command channel between THIRD Fleet and Southwest Pacific Commanders. It was not used as a Task Force Commanders circuit within the THIRD Fleet since traffic normally sent via this channel was of interest or addressed to other commands necessitating transmission via fleet broadcasts. The Task Force Common was guarded primarily as an emergency circuit during general quarters, during bad weather when groups became separated, and during operations in the China Sea. In the light of operating experience, it is believed that many of the frequencies assigned in the Basic Frequency Plan may be released for other: uses provided a few are retained for emergency use as set forth above. It is doubted if C. will ever be used for tactical circuits in the future.

(b) MAN and 608/808 equipment was used on inter-fighter director circuits. Each Task Group of Task Force 38 was assigned a separate group inter-fighter director frequency in the 30-40 me band and the group fighter directors were linked by a force inter-fighter director circuit in this frequency band in addition to the high frequency secondary frequency (2096 kcs).' The primary interfighter director frequencies were generally used except that when groups separated beyond range or traffic became heavy both the primary and secondary frequencies were used. Destroyer strike pickets stationed 25 to 50 miles distant used the secondary.

During radio silence and at night one VHF channel (140.4 mcs) was used for all inter-fighter director communications.

(e) The 30 - 40 megacycle band is considered insecure and its use was restricted to periods of no radio silence or when in contact with the enemy. This restriction was placed in effect upon receipt of several reports of strong signals and two way communications between units from 200 to 1700 miles apart. It is known to be used by the enemy and Jap voices were heard on these circuits several times during the operations.

[Trent Note: The 'reports' highlighted in bold above were likely Ultra decrypts.]

USS Hancock burns after being hit by a kamikaze off Okinawa, April 7, 1945.

Finally, we get to the General Robert E. Lee's operational plan for Antietam as a cigar wrapper captured by the Union soldiers sucked wind USN OPSEC.

The Japanese military had a complete plan for the invasion of Okinawa from an American officer on a downed US Plane. (Something similar happened during Operation Market Garden to General Montgomery.) and a "Fleet Task Binder" of all major US Navy combatants.

See: BULLETIN

Japanese Intelligence in WWII: Successes and Failures

I: Successes and Failures 5 1. Information gathering activities of the Imperial Japanese Army Historical records pertaining to the ...

It is by Ken Kotani, and the two most important paragraphs are below:

In addition to the questioning of prisoners of war, as one would expect, captured documents were an important source of information. According to Sanematsu it was the case that “The items which we obtained were mainly documents carried by airplane crew members. The U.S. forces’ “US Planning of Amphibious Operation in Okinawa (a top secret document of around 200 pages)” was extremely useful in preparation for decisive battles of Okinawa and Japan.”12

Among the captured documents was a black covered volume on which was written “U.S. Navy Task Binder” obtained by the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. It showed amongst other things, the equipment of major U.S. Navy vessels, their arrangement, and photos. Imai, who had seen this, recollected that “We saw things such as the Essex class aircraft carrier which we learned of for the first time. An outline of the equipment was as plain as day, with the rows of numerous anti-aircraft guns lined up along each side of its flight deck and so on. Even now, it is a real eye opener.

A Japanese radar expert looking at the "U.S. Navy Task Binder" mentioned above would have immediately seen the radar blind spot above a Essex Class carrier or any other US Navy major combatant.

The 200(+) page count of “US Planning of Amphibious Operation in Okinawa" makes "Joint Staff Study Iceberg" at 186 pages -- plus distribution list and approval pages -- the suspect document that the Japanese captured from Kotani Ken's US aircraft.

MUSICAL CHAIRS

In 2016 I read the post WW2 memoir, "DOUBLE EDGED SECRETS: USN Intelligence Operations in the Pacific During WWII" which answered a lot of questions as to why radar intelligence was so awful for Okinawa.

In Jan 1945, Nimitz had to move his theater HQ to Guam for logistics reasons as the Ulithi and the Philippines shipping routes skipped Hawaii and went straight to Guam. He could not take the whole Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas (JICPOA) to Guam because there was not enough room there for it. So Nimitz and his chief intelligence officer stripped off all of the "best" yeomen for Nimitz's new Advanced Intelligence Center (AIC) in Guam to support his theater HQ with "reach back" to Hawaii for administrative support, photo production and historical files.

There were not enough male yeomen of equivalent skill to replace them at JICPOA and it took until June 1945 to get female yeomen to both replace them and get them up to speed in their jobs. All of the above happened Jan thru June 1945. Right in the middle of planning the Iwo Jima and Okinawa operations. It was also when the British Pacific Fleet was extracting information from JICPOA for its participation in Operation Iceberg.

In the last quarter of 1944 USAAF General Harmon -- chief of land based aviation in the POA, turned over air technical intelligence to the JICPOA. It was simply too hard for the USAAF to do in the POA theater when USN intelligence got out of the combined allied & joint service technical intelligence in Australia in the summer of 1944.

The head of the JICPOA photographic section followed Nimitz to Guam as head of photographic intelligence for the AIC.

There was an additional compounding factor I mentioned in the Jan 2021 CIMSEC e-mail that I found in a 2006 book about JICPOA called "Spies for Nimitz: Joint Military Intelligence in the Pacific War".

The Navy personnel bureaucracy -- The Bureau of Navigation -- in Jan 1945 now considered Hawaii a rear area with the departure of Nimtz's theater H.Q. and wanted to rotate long time rear area folks to combat billets. This absolutely scattered all of JICPOA's best photo interpreters to the AIC, the various carrier group and amphibious group intelligence units, and a small photo processing facility at the Ulithi anchorage.

This same bureaucratic action also had the effect of scrambling the remaining yeoman in JICPOA who filed & distributed intelligence. The 80/20 rule applies here. About 20% of the yeoman did 80% of the distribution work because they knew the file system at JICPOA having years of experience there. So, about 10% of the best male yeoman went to AIC, and the remaining 10% of the "Effective 20%" were scattered to the four-winds by the same bureaucratic action that hit the photo interpreters.

NB: The US Navy lobotomized it's main intelligence arm in the middle of moving it's theater HQ for the first time in the war and it had inexperienced 2nd raters doing photo interpretation at Hawaii, and inexperienced 2nd raters distributing what they produced, during its two biggest amphibious operations in WW2!

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) afire after being hit by two Kamikazes off Okinawa, 11 May 1945

This is the "Dog Whistle" passage by US Navy Captain W. J. HOLMES (ret.) has left in in his "DOUBLE EDGED SECRETS: USN Intelligence Operations in the Pacific During WWII" about how badly Nimitz pole-axed JICPOA's effectiveness as an intelligence organization in the closing months of the war, (underline, italics & Bold are mine) --

When some of the submarines returned to Pearl Harbor, the Submarine Force held a critique to hear their skippers tell of their experiences.

Ed Blair, chief of the Mine Warfare Section, and I were invited to attend. I have always regretted that we did not take Lieutenant Harriet Borland along with us. She assisted Blair in preparing intelligence material for the operation, and she deserved recognition strictly on the basis of merit. Besides, I would have enjoyed standing up to introduce to that group of hard-bitten submarine skippers a beautiful and talented woman who, as a mine-warfare intelligence officer, made significant contributions to their success.

Harriet was the first woman to boast one of the rectangular yellow pass cards, with a photograph, which each one of us had to wear hung conspicuously around our neck while we were in the FRUPac building. Admiral Nimitz had a strict rule—no women on his staff. Technically, Harriet was not in violation of that rule. She was attached to Mine Force headquarters, a short distance from JICPOA, down Makalapa Drive. She worked in the Estimate Section by tacit agreement between the Mine Force and me, but I was not so sure that Admiral Nimitz would have recognized the niceties of this logic if we had flaunted Harriet's position.

As did every other shore-bound admiral with a sea command, Admiral Nimitz had visions of some day uprooting his staff and putting out to sea in a flagship. If that had happened and women had worked their way into indispensable positions on his staff, he could have been seriously handicapped. After CinCPac and the Advanced Intelligence Center moved to Guam, however, there was little probability that any of us who were left behind would be needed at sea. CinCPac took with him, when he moved forward, nearly all the best male yeomen. Replacement with other male yeomen was impossible, and it was becoming difficult for JICPOA to get the work out. I wrote a letter to Admiral McMorris, Nimitz's chief of staff, explaining the situation and asking for permission to employ female yeomen at JICPOA. My letter came back with an appended note in Admiral Nimitz's copperplate handwriting:

"Tell Captain Holmes he can employ one female yeoman for every male yeoman he has sent to Guam."

That solved my problem. The women who joined JICPOA in the last few months of the war were proficient, hard-working, and dependable. I am convinced that JICPOA would have worked more smoothly if we had started out with a solid core of women in many of the stable jobs.

Effectively, Nimitz took all his best and brightest male "Combat Intelligence Archivists" with him and the U.S. Naval Personnel Department support staff defenestrated JICPOA of the rest.

The "Hubris" of US Navy careerism -- both the permanent Navy bureaucracy & Nimitz's in particular -- met the "Nemesis" of a real thinking Japanese enemy with the crews of the US Navy's radar pickets paying the price.

And the US Navy went way the hell out of its way to bury the story.

I only ran across it because I am a multi-generation 'military brat' and DoD bureaucrat. Thus I could hear the almost 70 year plus "Dog Whistle" because I know how the hell this s**t works.

Plus, as a DoD quality auditor, I always validate against source documents. See SRH-20 attached at the top of page 22 of 24. The WAVE yeomen did not show up until June 1945.

Nor were the yeoman and photo interpreters the only, or even most important, organizational turbulence at JICPOA. Again from DOUBLE EDGED SECRETS pages 197 - 198

Greater changes in JICPOA followed the establishment of CinCPac's advanced headquarters on Guam on 2 January 1945. On the twenty-eighth the first echelon of the Advanced Intelligence Center went out from JICPOA to Guam, to be followed by others until the center had sixty officers and fifty enlisted men. Commander Richard O. Green, who was also the fleet photographic officer, became the officer-in-charge of the Advanced Intelligence Center. This was a very happy choice. Photo-interpretation had become the primary source of operational intelligence, and Green had excellent qualifications for the job. He achieved close cooperation with the 21 st Bomber Command and with CinCPac's Intelligence Division, to everyone's benefit.

When Admiral Nimitz moved to Guam, Captain Layton, the fleet intelligence officer, moved with him. Since the Estimate Section had always supported fleet intelligence by coordination of Ultra information with other sources, he asked to have Mac Showers go with him to set up a fleet combat intelligence center. This left a big gap in the Estimate Section, but Paul Yardley and Alex Johnson were well qualified to fill it. Admiral Lockwood moved the operational headquarters of his submarine command to the submarine tender Holland in Apra Harbor, Guam, on 24 January. Voge moved with him, ending his daily conference with the Estimate Section. To replace it, a special code was created and held only by the Estimate Section and the Submarine Force's Operations Division. Guam rapidly developed into the center of operations for the war against Japan, and for a while it appeared that Pearl Harbor was destined to become a rear area of diminishing importance. However, both CinCPac and ComSubPac had to retain administrative headquarters at Pearl Harbor, and Admiral Spruance and the Fifth Fleet's planners remained there to map out that fleet's operations for 1945. It was planned to move a large part of JICPOA forward, but this proved to be impossible because of the crowded conditions on Guam. Twitty had to spend much of his time there, but the administrative work of JICPOA continued to be done at Pearl Harbor. Most of the Translation and Interrogation sections were left behind, along with a large part of the photographic reproduction and lithography operations and the Bulletin Section. Other sections learned to operate with representatives forward, with most of the work being done at Pearl Harbor. The solution was found in greatly improving communications. The Army's intelligence communications were merged with FRUPac's and the joint code room was right across the hall from the Estimate Section in FRUPac's building. This made it more convenient for Captain Layton, in Guam, to communicate with CinCPac's administrative headquarters in Pearl Harbor through FRUPac than through CinCPac's regular channels, which sometimes resulted in giving me chores that had little connection with intelligence.

LESSONS LOST

All Nimitz’s intelligence distribution problems via headquarters movement, reorganization and personnel churn points to how flag ranks hide military “lessons learned” when they reflect upon their brass and post-budgets. Specifically, the issue of how the movement of big centralized Allied HQ’s -– Eisenhower’s & Nimitz’s -- tended to screw up combat operations in 1944-1945.

A lot of the issues with the False Gap being closed in Normandy had to do with the movement of SHAFE from England to France while it was going down.

Then there was this thing called the Ardennes Offensive. It was not Western Allied intelligence's best moment. And in part it was due to the HQ movement of SHAEF from Paris to Versailles.

General Spaatz in particular complained that Ultra intelligence distribution and analysis in Nov 1944 -- after his HQ's move to Paris France from England and before it moved to Versailles -- was nowhere near as good as June 1944.

MacArthur, please note, ran a very -Decentralized- theater command with the various service elements being in charge of their own operations. ("Command and Service Coordination" per pre-WW2 US Navy-War Department Doctrine) This meant his being mobile and even out of pocket when command decisions had to be made had little real effect on his theater.

The SWPA theater decision to go straight to Leyte in lieu of Mindanao was made by General Kenney while MacArthur was on a US Navy cruiser heading for an amphibious operation under radio silence.

This is part of the reason why MacArthur was far more mobile, and successful while mobile, with his theater command posts than either Ike or Nimitz.

Part of what was going on with the thinking in Nimtz's command after Saipan was that the end of the war looked close at hand, just as it did at SHAEF in Nov-Dec 1944. This meant peace time like bureaucratic rotations were simply not looked at as a war fighting impairment. Other things were on the agenda.

This, as far as I can tell, was "normal" in that victory seemed at hand and post-war politics was affecting current operations as nations, institutions and factions in both were thinking past war's end.

IMO, the "lesson learned" was that Centralized-style theater commands could not, and should not, be running combat operations in the middle of a geographic move.

Given who was in charge of the US Army and Navy respectively after WW2, and what happened during the war, that "lesson learned" was never written.

Japanese Kamikazes attack the American fleet, Okinawa, 1945

ApPendiCE One

IJN Naval Ground Force Notes & Definitions:

** Kavieng, New Ireland. IJN Base Forces and Special Base Forces provided security, defense, supply, communications, repair and other functions at IJN facilities and installations outside the four home islands.

*** "Sasebo Sailor Corps" -- The "official" USN/USA translation of kaiheidan was "naval barracks."

A naval barracks in the IJN was a unique command compared to the barracks in the USN, RN, and KM. It had a number of functions:

Recruit training (larger barracks only)

Quarters for transient personnel

Quarters for permanent party personnel

Civil Defense (on a limited scale)

Civil Policing (emergencies such as riot or disturbance)

Ground Defense (day to day base/facility security plus the fielding of ground defense battalions in case of invasion)

Some of these barracks were huge commands. All four barracks in the Sasebo Naval District combined had somewhere in the neighborhood of 25,000 men assigned when the war ended. Yokosuka was even larger. IJN recruit training covered only the basic essentials. Advanced schooling/training was conducted elsewhere. Off the top of my head, I think the radar school was located in Yokosuka.

The primary functions of the kaiheidan were recruit training and berthing. Its use as garrison troops/marine infantry was strictly on an ad hoc emergency basis. The kaiheidan was just one of many commands subordinate to the naval district.

The lookout stations were part of the keibitai guard force which was parallel to the kaiheidan.

kaiheidan = naval barracks (usually commanded by Rear Admirals)

chinjufu = naval district (usually commanded by Vice Admirals)

An IJN naval district encompassed a wide geographic area. Its headquarters was located on a naval base but it was not the naval base. A district could have more than one naval base/naval station in its area. Each naval base had its own Commanding Officer who reported to the district commander. The naval barracks commanding officer was another officer who reported to the district commander. I believe the 43rd Minesweeper Division and the Oshima Coast Defense Unit were separate organizations with their own individual commanders who were subordinate to the Okinawa Base Force commander (Ota).

APPENDICE TWO

Generic naval district Chain of Command:

Naval District

Naval District Headquarters

Naval Base

-Naval Base Headquarters

-Communications Department

-Supply Department

-Accounting Department

-Construction Department

- - Assigned Construction Units

- Harbormasters Office

- Navy Yard (sometimes referred to as a "naval arsenal")

- Naval Hospital

- Naval Prison

- Naval Fuel Depot

- Naval Magazine

Naval Barracks

Special Naval Landing Force(s)

Submarine Base

Naval Air Group(s)

Guard Unit

-Defense Squadron

-Lookout Stations

-Anti Aircraft Artillery Units

The district could also include units which occupied real estate in the district but which were operationally subordinate to organizations outside the district. These typically were specialized training commands and schools, research facilities, weapons plants, and so forth.