OPERATION COUNCILLOR, June 10-13, 1944

“We would operate from Trincomalee in what were known as ‘Club Runs’. We would go down with one or two carriers and some cruisers, and we would go and attack Japanese bases in Sumatra in particular ... We really started to learn our job against the Japanese for our eventual part in the British Pacific Fleet.”

With USS Saratoga gone, HMS Illustrious continued to work up her air group in the vital skills of rapid launch, form-up and deployment.

But she was again operating Fairy Barracudas. The experiment with Avengers, while successful, was over. They were back aboard their escort carriers, scouring the trade routes for enemy submarines.

An opportunity to put Illustrious’ air wing to the test once again arose in mid June. It was also an opportunity for the ship's new captain, Charles Lambe. As with Captain Mackintosh being removed from HMS Victorious immediately after operations with the US fleet in 1943, Illustrious' Captain Cunliffe had been relieved immediately after USS Saratoga's departure.

But now the US navy had requested a diversion operation in order to help mask the opening stages of the attack on Saipan in the Marianas.

This diversion would be labelled Operation Councillor. It would involve HMS Illustrious and the escort carrier HMS Atheling.

Atheling had been in the Indian Ocean as a trade protection carrier since May. She carried 10 Seafire FIIIs of 889 Squadron, and 10 Wildcat Vs of 890 Squadron.

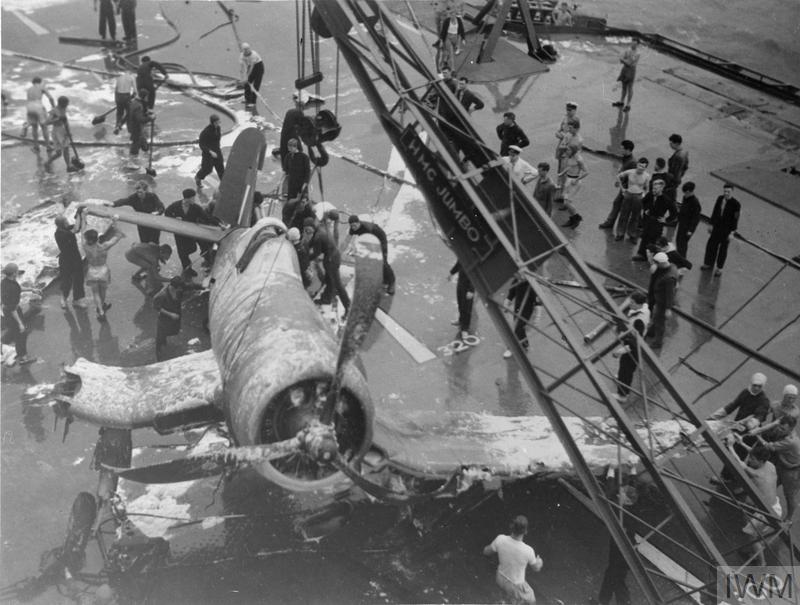

In this mission, Atheling’s role was secondary – though necessary. With her full wing in the air, a serious risk was posed during HMS Illustrious' recovery operations. A series of severe deck crashes could result in most of her aircraft running out of fuel and being forced to ditch.

The escort carrier was therefore present to operate as a ‘spare deck’, as well as a source of supporting CAP.

The submarine HMS Surf took up position 300 miles west of Sabang, transmitting false signals designed to give the impression that a RN carrier group was about to launch an attack.

HMS Illustrious deployed CAP fighters and air patrols, watching her radar for any Japanese response. She was acting as bait. No strike was planned.

No Japanese response emerged.

Nevertheless, the exercise provided a valuable lesson: at 12kts slower than a fleet carrier, combined operations with escort carriers had proven not to be viable for fleet-scale operations.

“I collected a shell— probably 20 mm— from below and ahead which passed neatly through the propeller without touching it. It sheered off the vanes from the top centre cylinder of the engine and finally burst through the engine cowling, leaving something like a head of aluminium cos lettuce sticking out on top.”

OPERATION PEDAL, June 19-21, 1944

Despite being the only fleet carrier operational in the Eastern Fleet, HMS Illustrious was to maintain a high tempo of operations.

But this was proving difficult: her centreline shaft was beginning to vibrate severely at higher speeds. Clearly the wounds from her ordeal at the hands of Fliegercorps X in January 1941 had not been fully healed.

Fleet Air Arm pilots and observers sleep on camp beds on the quarterdeck of HMS Illustrious to catch what cool sea air they can during the Andaman Island operation.

After Operation Councillor, Illustrious had undergone an air-group shakeup.

A third Corsair squadron was embarked to improve fleet defence. To make room for the extra fighters, her two Barracuda squadrons were cut back.

1830 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

1833 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

1837 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

810 Squadron, 9 Barracuda II

847 Squadron, 6 Barracuda II

With a total of 57 aircraft aboard, HMS Illustrious was operating at the edge of her capacity. Not only was there little space left in her hangars and on deck, there was next to nowhere for the extra crews and support personnel to sling their hammocks.

She would be immediately assigned to attack the harbour and Japanese military facilities of Port Blair.

With her sailed Task Force 60 – the major elements of the Eastern Fleet.

Battleship: Richelieu

Battlecruiser: Renown

Cruisers: Nigeria, Kenya, Ceylon

Destroyers: Quilliam, Quality, Quickmatch, Rotherham, Racehorse, Relentless, Roebuck and Raider

ASR Submarines: Tantivy, Clyde

At dawn on June 21, under a cloud cover of 1500ft, this force took up position about 95 miles west of Port Blair.

Illustrious – without the ‘spare deck’ of HMS Atheling – launched a strike 15 Barracudas backed up by 16 Corsairs. A CAP of eight Corsairs was established above the task force itself.

The Barracudas were tasked with bombing harbour facilities. Half of the Corsairs were to strafe shipping, a seaplane base, a sawmill and a headquarters building. The other half were sent to two nearby airfields.

The FAA met stiff anti-aircraft fire as they dove through scattered rainstorms over their targets. One Barracuda was shot down over Port Blair while a damaged Corsair managed to struggle back over the coast for its pilot to be rescued from the water.

Four further damaged aircraft limped their way home towards HMS Illustrious.

It had proven to be a nerve-wracking mission. Any mishap could have resulted in Illustrious losing much of her air group. However, the pilots and deck crews proved they were now up to standard.

At the height of the operation, Illustrious had 53 of her 57 aircraft airborne. It took an hour to recover all aircraft successfully.

The mission was deemed a moderate success: Two Barracudas had to return before dropping their bombs with engine failure. But there was an unacceptably high bomb arming and release-failure rate among the Barracudas over target.

No Japanese fighter opposition was encountered, though handful of Japanese aircraft were claimed as destroyed on the ground.

Shortly after Task Force 60 returned to Ceylon, the RN fleet carriers HMS Victorious and Indomitable pulled into Columbo.

At last, the Eastern Fleet could mount a meaningful carrier strike.

Rear Admiral Aircraft Carriers, aboard Indomitable, was to be Clifford Moody - a veteran of carrier operations in the Mediterranean.

HMS Indomitable was operating one of the largest air groups she would carry during the war, 56 machines. After Operation Crimson (which she would miss), this air group would fall dramatically - probably due to the demands placed on her accommodation for extra admiral's staff.

1836 Squadron, 14 Hellcat I

1839 Squadron, 14 Hellcat I

815 Squadron, 14 Barracuda II

817 Squadron, 14 Barrcuda II

“Daybreak is an unpardonable hour to attack anybody. A man is never at his best when struggling into a pair of trousers, particularly when the process is somewhat hindered by bursts of incendiary fire zipping through the hut. Certainly the Japs who. rushed out of those barracks, some of them clutching platefuls of whatever the Japanese soldiery ate for breakfast, must have disliked it intensely.”

OPERATION CRIMSON, JULY 22-25

After three weeks of lectures and demonstrations from HMS Illustrious’ pilots and flight crew, HMS Victorious would to be put to the test.

She sailed with HMS Illustrious to cover a bombardment of Sabang by the heavy units of the Eastern Fleet.

The two fleet carriers were to provide CAP for themselves and the warships. HMS Indomitable was not ready. Nor were her new photo-reconnaissance Hellcats (organised so urgently by Admiral Somerville immediately after USS Saratoga’s departure).

HMS Illustrious sailed with the same 57-strong air group she had carried on Operation Pedal (though some accounts say she had left the six Barracudas of 847 Squadron behind).

A Barracuda in Eastern Fleet markings flies over an ASR submarine.

HMS Victorious was only carrying fighters: three Corsair squadrons (1834, 1836 and 1838), totaling just 39 machines.

1834 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

1836 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

1838 Squadron, 11 Corsair II

Task Force 62 itself comprised:

Battleships: Queen Elisabeth, Valiant, Richelieu

Battlecruiser: Renown

Cruisers: Nigeria, Kenya, Gambia, Ceylon, Cumberland, Phoebe, Tromp

Destroyers: Relentless, Rotherham, Racehorse, Raider, Roebuck, Rocket, Rapid, Quilliam, Quality and Quickmatch

ASR Submarines: Templar, Tantalus

The carriers took up position some 35 miles north of Sabang before dawn, at 05.30. Illustrious launched 18 Corsairs, while Victorious sent up 16. Eight from each carrier was tasked with attacking Sabang airfield. Two from Illustrious were sent to a radar/radio station. The remainder were to form a CAP over the bombardment ships.

The battleships began to move up to the coast at 06.40.

However, the carrier operations were not unfolding according to plan.

The launch had been intended for 33 minutes before sunrise. But deck handlers did not have enough light, or suitable equipment, to carry out their duties in the dark.

It was a poor comparison to HMS Illustrious’ landmark night-time strike against Taranto just four years earlier.

The launch, delayed by five minutes, was a fumbled affair in the gloom. Then the aircraft of the multi-carrier strike force simply took too long to form up, further delaying the operation.

Their task was to attack the airfields of Sabang, Lho Nga and Kotaraji.

Henry "Hank"Adlam: On and Off the Flight Deck: Reflections of a Naval Fighter Pilot in World War II

This was my first sight of a Hellcat. I had heard about the aircraft, of course, and knew that the American Navy pilots had flown this latest fighter with great success against the Japanese in the Pacific. The Hellcat, with its round fuselage leading back from a huge radial engine, was basically like a Wildcat to look at but very much bigger. In fact, it seemed to me then at first sight to be a monstrously large aircraft for a single-seater fighter. One good factor, I could see immediately, was the wide undercarriage with each oleo leg mounted under each wing. Its armament was six 0.5 Browning machine guns and it was provisioned with racks for four rockets and for two 500lb bombs. In fact, it was a very fast and formidable Fighter/ Bomber. I spent half an hour reading the Pilot's Notes, sitting in the spacious and well laid out cockpit while Haberfield pointed out the position of the various controls and described the aircraft's flying characteristics. Then, no good thinking about it any longer, it was time to go. From the nearby Ready room, I collected my new khaki flying suit and tropical helmet with oxygen mask, and made myself ready mentally to fly the Hellcat. I climbed up the port wing to the cockpit and settled down on the parachute seat while the maintenance crew strapped me in. A quick look round the instruments and controls to remind myself of their unfamiliar position, checked the movement of the flying controls and then signalled the crew, by now waiting on the ground, that I was ready to start up. The huge engine bellowed into life. I checked the magnetos on the run-up and was ready then to taxi out on to the runway. Given clearance from the control tower to take off, I opened up the throttle fully and felt the acceleration from the powerful radial engine; a much greater response than the little Wildcat could give. Comfortably airborne after a short take-off run, I began a climb to 12,000 feet where I intended to carry out some stalls and slow flying with wheels and flaps down. The weather was good; the midday cu-nim clouds had not yet built up. Down below I could see Trincomalee harbour crowded with shipping and, either side of it, the coastline of sandy beaches for miles and, inland, the jungle covered hills. The Island of Ceylon was as beautiful from the air as it was from the ground. I found the Hellcat to be a gentle giant; admittedly she dropped fast like a brick when stalled, but with no vicious roll-over. I practised slow flying with maximum drag, as for a deck-landing approach and, to finish, some steep turns. Satisfied with my control and handling of the aircraft, I returned to the aerodrome to make a normal landing. Later in the afternoon I took off again and climbed up to 32,000 ft to see how she handled at height and found control at that level to be better than anything I had ever flown before. Then down to 12,000 ft again for some of my aerobatics which, dreadfully imprecise as usual, nevertheless enabled me to learn how she handled.

“I was directed towards the enemy at 1645 hrs and sighted five aircraft. There was a large storm astern the fleet, but Victorious managed to vector me onto the enemy. A Japanese aircraft dived past me and I followed him down, hitting him on the port quarter with a long burst of fire. He was weaving, but flames were coming from his port wing. He disappeared into cloud and, following him, I came out dead on his tail at a range of about 100 yards. After another long burst, the aircraft went up in a sheet of flame.”

But 1838 squadron’s Corsairs went off course, and stumbled about in the darkness attempting to locate its target through old maps.

It was still dark as the RAMROD squadrons strafed the airfields. Anti-aircraft fire was intense, and targets of opportunity almost invisible in the deep pre-dawn shadows. One damaged Corsair limped over the coast and out to sea where the pilot was rescued.

Nevertheless, two Japanese aircraft were claimed destroyed, and two damaged, on the ground.

The battleships opened fire on the harbour facilities and barracks of Sabang at 0700.

The cruisers attacked a radio station on Pulo We Island while waiting for responding Japanese shore batteries to reveal themselves by opening fire.

The destroyers Quilliam, Quality and Quickmatch with the Dutch cruiser Tromp surged towards Sabang harbour, arriving once the battleship bombardment had lifted. They shelled and torpedoed harbour installations.

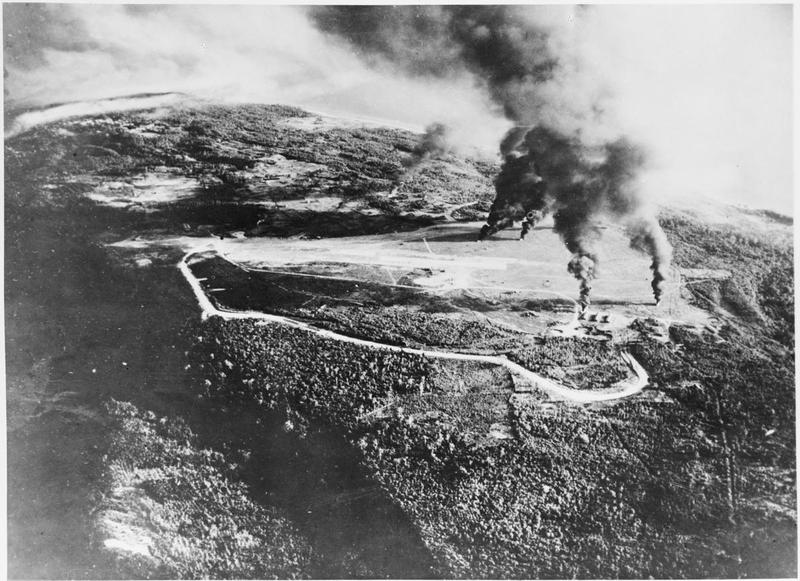

Two small ships were sunk, oil facilities were set alight and harbour infrastructure destroyed.

But Japanese shore-battery fire was accurate: only Quickmatch would not be hit. Damage, fortunately, was slight.

The fleet withdrew at 0930. Two Japanese reconnaissance aircraft then closed on the task force in an effort to ascertain its strength. Both were shot down by the CAP.

As the sun dipped towards the horizon, the fleet’s radar detected a flight of what were judged to be 10 A6M Zeros (though they were almost certainly Ki43s) at a range of 50 miles. A force of 13 Corsairs was sent against them, claiming four kills (some accounts say two kills, two damaged).

HMS Illustrious' Corsairs also claimed a Ki-21 'Sally'.

These were the first kills by the Corsair while operating from an aircraft carrier.

“The results will hearten all forces in South-East Asia.”

“When the fleet approached to within five hundred miles off the enemy coast, our Hellcats commenced constant patrols of four aircraft to provide a protective umbrella against potential air attack. No such attack materialised throughout the whole operation and it was a boring task. While we were stooging about above the fleet, the Corsairs from Victorious were strafing the Japanese airfield in the area ... My guess was that our two Hellcat squadrons had suffered such a long period in the doldrums, with unserviceable aircraft through lack of spares, that we were considered to be inexperienced and not quite up to scratch as yet.”

OPERATION BANQUET, August 24-29

Once again, the carrier air groups underwent a shake-up.

Both HMS Illustrious and Victorious would surrender their third Corsair squadron. Victorious would now bring aboard a TBR squadron.

Victorious would now carry a balanced strike group: 28 Corsairs and 21 Barracudas.

1834 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

1836 Squadron, 14 Corsair II

822 Squadron, 21 Barracuda II

Indomitable had had reduced her numbers slightly:

1839 Squadron, 12 Hellcat I

1844 Squadron, 12 Hellcat I

815 Squadron, 12 Barracuda II

817 Squadron, 12 Barracuda II

Importantly, HMS Indomitable’s Photo Reconnaissance Hellcats (organised so urgently by Admiral Somerville immediately after USS Saratoga’s departure), were to provide photos for strike damage assessment.

HMS Illustrious, however, was headed south-west. She had been diverted to a long-overdue refit at Durban. It was the first attention she would receive for more than a year. Top of the priority list was to strip down and examine her centreline shaft. She would be off the front line until mid October.

HMS Victorious and Indomitable would maintain the pressure against the Japanese. Once again the RN had been asked to provide a distraction from an unfolding USN attack, this time on Hollandia.

Padang airfield, Emmehaven harbour and the Indaroeng Cement Works were to be their targets.

The veteran (but heavily modernised) battleship HMS Valiant had suffered a broken back when the floating dock she had been in collapsed. She would never be repaired.

HMS HOWE seen from the flight deck of INDOMITABLE.

The modern battleship HMS Howe, however, had arrived earlier that month and took up Valiant’s place in Task Force 64.

The fleet left Trincomalee on August 18. On August 22, the force refuelled from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Easedale.

The next day, August 23, Admiral Somerville - who had remained in Ceylon - was relieved. After holding together his ramshackle collection of warships since March 1942, his tenure as C-in-C Eastern Fleet was over. Thanks largely to Mountbatten’s intransigence.

Now Admirals Sir Arthur Power and Sir Bruce Fraser took up the task. It was Fraser's job to assess the units of the Eastern Fleet, and divvy-off the best of them into what would soon be his own British Pacific Fleet. Power would take over operations in the Indian Ocean.

As the politics unfolded back in Ceylon, Task Force 62 pressed on.

By 05.50, August 24, the fleet - under the command of Rear-Admiral (Carriers) Chester Moody - was at its launch position. The sky was clear. The seas were slight. The wind was just six knots.

The carriers had to race through the waters at 27 knots to generate enough wind-over deck to get their aircraft airborne.

HMS Howe proved incapable of keeping up – despite having a designed top speed of more than 28 knots.

Each carrier launched 10 Barracudas, each carrying 500lbs bombs. Escorting this strike force was 19 Corsairs from Victorious.

A little more than an hour later, at 07.10, a second strike wave was launched.

This time it was made up of nine Barracudas from Indomitable and three from Victorious. The escort was 12 Corsairs, again from Victorious.

Henry "Hank"Adlam: On and Off the Flight Deck: Reflections of a Naval Fighter Pilot in World War II

... the heat on board was still difficult to bear since Admiralty ships were not designed for the tropics with air conditioning or anything of that sort. Fresh water for drinking and for showers too was in short supply.

I doubt if there was anyone on board who did not suffer from prickly heat, which could drive a man dotty with its irritation but, at least, in my opinion, it was not as bad as the mosquitoes ashore.

In all Carriers in the tropics, the worst area was the hangar where the maintenance crews worked, wearing only shorts and gym shoes. It was a hell's kitchen of a huge enclosed space with the heat and the bedlam of the constant noise from the intense repair work, which frequently had to continue through the night.

I felt it was important, as did most pilots, to spend some time with the men working on our aircraft there, if only as a gesture of appreciation for keeping us safely airborne.

I went down to visit the engine-room of Indomitable once and found the heat to be appalling and unbearable unless one was accustomed to it, but it seemed to be a more orderly and calm environment compared to the hangar.

“After the attack, the fighters roamed the area looking for the most impressive buildings in the area. These would then be machine gunned in the hope that the Japanese overlords were in residence.”

The aircraft arrived over Emmahaven and Padang to discover the ports largely abandoned. Admiral Somerville’s tactic of avoiding pre-raid reconnaissance in order not to reveal his hand to the enemy had backfired.

The Barracudas nevertheless carried out their strike and one Corsair was lost to light anti-aircraft fire. Two ships totaling 6000tons were claimed as damaged.

The Indaroeng cement works - the only such production facility in South-East Asia - was put out of action for two months.

Operation Banquet was to reveal several ongoing issues for the British fleet.

This one strike and its associated CAP patrols had consumed almost a quarter of HMS Victorious’ available aviation fuel. And HMS Howe, with her poor speed, was burning through fuel at an alarming rate.

Task Force 64 had to slow to a maximum economical speed to guarantee the battleship could make it back to Trincomalee.

OPERATION LIGHT, September 17 and 18

“The fleet arrived off Sumatra to find what I called the ‘Elephant Monsoon’ sitting over the top of the whole area; in other words thick cloud at low level and pouring, incessant rain with little wind. This was a situation which I dreaded and hated because we aircrews had to sit around in Ready rooms waiting for a decision from the powers that be whether they would send the strike off or not.”

Admiral Fraser’s first experience of combat in the Far East would be two days of operations against Japanese airfields and infrastructure on Sumatra.

Unlike Somerville, Fraser also wanted fresh photographic reconnaissance of potential targets and detailed briefings for his pilots. Fresh PR Hellcat units were to be put to the test.

HMS Indomitable and Victorious deployed as part of Task Force 63 with the same air groups as they had carried for Operation Banquet.

(Ed's note: Hobb's Carrier Operations in World War II states Victorious only carried 19 Corsairs in 1834 Squadron and 18 Corsairs in 1836 Squadron for this strike for a total of 37 machines. But I have seen several references to Barracudas operating from Victorious in this operation - so I am inclined to go with sources that say she was operating with the same group as in Banquet)

‘Light A’ was to take place on September 17 and involve a fighter sweep over Japanese airfields in the area of Medan and Belawan Deli, as well as a photographic survey of Aru Bay. Much of this had to be abandoned. The weather was untenable, with heavy drenching rain.

‘Light B’, on September 18, was an air strike on railway facilities at Sigli, Sumatra.

It was a shambles.

Both carriers turned into the 10kt wind at 6am. Without Illustrious’ experience, the Indomitable and Victorious continued to struggle. Form-up took 40 minutes.

Each carrier launched 10 Barracudas. Escort was provided by eight Hellcats and 16 Corsairs.

Much of the delay was caused by Indomitable realising, at the last minute, that the wind was insufficient to allow all her strike aircraft to be launched in the one range. Some had to be hastily stowed back below in order to provide sufficient deck space for take-off.

One of Indomitable’s Barracuda’s ditched on take-off.

Three Corsairs quickly returned to Victorious. All had been part of the deck park, and had had their engines drenched in the previous day’s rains. Indomitable’s deck-park aircraft also suffered – with several becoming unserviceable as they were readied for launch.

Bad weather lingered over the target. But anti-aircraft fire was light and no Japanese aircraft encountered.

The Barracudas were hasty in their attack runs, hitting the main targets but missing several of the secondary objectives. The top-cover Corsairs had gone astray, abandoning their escort position to strafe ground targets.

A Barracuda from HMS VICTORIOUS photographed during the attack on Sigli.

“As escorts, we had a grandstand view of the successful bombing of the railway yards. There was very little flak and no Japanese fighter aircraft so nothing really into which we could sink our own teeth.”

All the while, several pilots had accidentally left their radio transmitters turned on – effectively jamming all communications with flight leaders and the carriers.

Once again the fuel reserves of the Barracuda strike aircraft proved to be cause for concern. HMS Illustrious and Indomitable let themselves get out of position during landing operations, causing the approach circuits for the carriers to dangerously overlap. This caused further delays – which the Barracuda could not afford.

As a result, Rear Admiral Moody reported back to London that the torpedo-dive bomber simply did not have a sufficient strike radius for operations in the Pacific.

Indomitable’s PR Hellcats, after missing the previous day’s mission, took to the skies on an alternative reconnaissance flight. They were sent to photograph parts of Northern Sumatra and the Nicobar Islands. Unfortunately they strafed a target of opportunity – the submarine HMS Spirit, which had surfaced in an attempt to rescue the crew of a ditched Barracuda.

The comedy of errors wasn’t over yet.

Victorious had launched her afternoon CAP of Corsairs without long-range fuel tanks.

When HMS Howe’s radar lit up with aircraft moving across the islands, though not towards the fleet, the fighters were simply not able to take advantage of the rare opportunity.

Admirals Fraser and Moody were not impressed. As the fleet travelled home, the pair called together their staffs and instigated an intense training program to begin the moment they returned to Trincomalee. Performance simply had to improve.

FAA commanders, however, argued intelligence about the targets had been virtually non-existent, and their maps had been out of date. This had added considerably to the difficulty the pilots faced.

Their objections were duly noted.

“The special training we were to undergo was in the procedures of forming up into large groups of Hellcats and Corsairs to fly as a Wing in support of the Avenger bombers. The purpose was to train and accustom six squadrons or more of aircraft to form up and formate together, regardless of bad weather and over large distances, to a given target. There was a much stronger sense of reality and urgency now about this form of Wing training since we were all aware that very soon the British Pacific and Far East Fleet would expect to join with the US Navy in their battles against the Japanese in the Pacific.”

OPERATION MILLET, October 17-19

Once again, the Americans wanted a diversion – this time for landings in the Philippines. Once again, HMS Indomitable and Victorious put to sea with Task Force 63.

The idea was to make it appear as though Britain was about to invade the Nicobar Islands.

Task Force 63:

Battlecruiser: Renown

Cruisers: London, Cumberland, Suffolk,

Destroyers: Relentless, Raider, Norman, Quilliam, Queenborough, Quiberon, Van Galen, Whelp, Wakeful, Wessex and Wager

Both carriers retained their established air groups and operated in a sub-group with the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Phoebe with the destroyers Whelp, Wakeful, Wessex and Wager. The remainder of the fleet was divided into a group Renown and the Q-class destroyers, and another group centered on the cruisers.

Indomitable launched 10 Barracudas covered by eight Hellcats to hit Nancowry harbour on October 17. Eight Corsairs from Victorious provided top cover.

Another 19 Corsairs flew off Victorious to suppress activity on nearby airfields and attack targets of opportunity.

The Japanese were surprised, harbour facilities were demolished and a merchant vessel in the harbour sunk.

Two Corsairs were shot down and another three damaged during their strafing run – made after the main attack had alerted defences. One of Indomitable’s Hellcats crashed on landing, killing its pilot.

One Barracuda may have suffered a relapse of a fault that had grounded the type a year earlier (rivet failures on its main wings): it was observed to fail to recover from its dive. However, the aircraft may also have had its controls shot away or its pilot killed.

Either way, Operation Millet would prove to be the Barracuda’s last active deployment from RN fleet carriers for the war.

Task Force 63’s heavy warships bombarded Car Nicobar, with Hellcats from Indomitable spotting.

Unusually, the British task force would linger in the area. This was largely due to the bad weather - plans to strike Sabang were unviable. However, the big guns of the Task Force would again bombard Car Nicobar targets during the morning of the 19th.

As the fleet prepared to withdraw on the 19th, a Japanese twin-engined reconnaissance aircraft flew high over the bombardment force at 08.40 without being intercepted. Two of Indomitable’s Hellcats, on spotting duty, attempted to climb, but were unable to close.

HMS Indomitable was unaware of developments: a technical fault had taken her Action Information Network offline.

So when a group of unidentified aircraft was detected on radar at 09.30, the CAP was not primed for action. Indomitable’s Hellcats again failed to intercept.

Victorious’ Corsairs finally managed to engage when the hostile force was just 12 miles north east of the carrier formation. It was a formation of Japanese Ki43 Oscar fighters from the 1st Reserve Flying Unit, nine flying at 7000ft with another three at 16,000ft as top cover.

The dogfight whirled over the fleet from 09.50 to 10.30. The bombardment force CAP Hellcats scrambled to join in.

Seven Oscars were claimed to be shot down by the FAA. Japanese records reveal four to have been shot down and two force-landed. Japanese accounts credit two of these pilots as diving their burning aircraft into British ships, which then sank. No such event occurred.

However, two Corsairs of 1834 Squadron were lost by the FAA in this engagement, as was a Hellcat of 1844 Squadron.

Despite the losses, Major 'Ronnie' Hay aboard HMS Victorious was impressed with the performance of the Corsair. He would write after this action:

‘The Corsair was just the right aircraft for that war. It was certainly better than anything we had, and an improvement of the Hellcat. It was more robust and faster, and although the Japanese could out-turn us in combat, we could out-climb, out-dive and out-gun him. By far the most healthy improvement was its endurance, as with about five hours worth of fuel in your tanks you didn’t have the agony of wondering whether or not you would make it back to the carrier.’.

The three-day operation also intended to test measures put in place to keep the RN carrier force on station. While refueling and reprovisioning at sea was conducted successfully, it was obvious the tankers then with the fleet were too slow and the fuel-line astern method of refuelling capital ships was inefficient.

It was also to be the last action involving fleet carriers acting as part of the British Eastern Fleet.

“It had been quite a significantly successful operation. Firstly, because the fleet with its Destroyers had been able to remain in the combat area for several days, having completed refuelling at sea with some success, such success being vital in preparation for operations with the United States Navy in the Pacific. Secondly, our fighters had met the Japanese fighters for the first time and had proved themselves to be superior.”

THE BRITISH PACIFIC FLEET IN THE EAST

“At the time of our arrival at Colombo on the 10th December, the ultimate employment of the Fleet was still uncertain... The Commander-in-Chief therefore left instructions with Admiral Power that air squadrons should first be eimployed in the Indian Ocean in attacks on the oil refineries in Sumatra, which were of great value to the Japanese war potential. This would hurt the enemy in a sensitive spot, and at the same time give our aircraft carriers the experience they needed.”

Operation Millet was to be the Eastern Fleet’s last involving the Royal Navy’s armoured carriers.

The race to prepare the British Pacific Fleet had been gathering pace.

On November 22, 1944, Admiral Fraser took up his new flag and Task Force 118 was formed.

For the second time, Rear-Admiral Aircraft Carriers Clement Moody would be sidelined by the high-profile (but inexperienced in carrier operations) Rear-Admiral Vian. The dashing destroyer captain had taken Moody’s command at Salerno. He had arrived at Ceylon aboard the fleet carrier HMS Indefatigable. Now he was to take the British Pacific Fleet.

The battleship HMS Howe had arrived in August. A steady stream of somewhat modernised and tropicalized cruisers and destroyers had been trickling into Ceylon. Others were scattered to Malta, Durban, Simonstown and Sydney to have their anti-aircraft armaments urgently upgraded.

Most importantly, HMS Illustrious had returned from South Africa and the new carrier HMS Indefatigable arrived from Europe in December.

With four fleet carriers, the fledgling BPF could put up a credible strike force of some 230 aircraft.

The Eastern Fleet would not be totally devoid of carrier strength, however. The reduced demand for ASW and raider protection had freed up the escort carriers. These ships, Ameer, Atheling, Battler, Begum and Shah, would remain behind with the politically unpalatable FS Richeleau and older (and shorter ranged) units of the Royal Navy to maintain the pressure against Japan in South East Asia.

The fleet carriers, now designated the First Aircraft Carrier squadron (1ACS) scrambled to familiarise themselves with their new Avenger bombers. While incapable of carrying the British torpedo, the Avenger had the endurance the Barracuda did not. But, unlike the Barracuda, they were not dive bombers. So crews had to adapt to new attack profiles involving shallow, glide-bomb approaches.

This delayed the BPF's planned departure to Australia from December to January. There were simply no facilities ready for the new Avenger aircraft in Australia, and it was vital the fleet become as proficient as possible in their use as fast as possible.

The arrival of new carriers and new aircraft meant a renewed need for training and operational experience. Admiral Fraser recognised this, and left orders for Japan's three oil refineries in Sumatra - on Palembang, in southern Sumatra, and at Pangkalan Brandan, be attacked.

The series of strikes, beginning with Operation Robson, was to be given the over-all code-name OUTFLANK.

“Refineries at that time were particularly suitable targets for precision dive bombing by naval aircarft, as opposed to area bombing by high-flying heavy bombers of the air forces. To put refineries out of action it was necessary to hit certain small but vital targets, set in the midst of a large, less important field.”

HMS UNICORN

The maintenance carrier HMS Unicorn had proven invaluable during her long deployment to the Indian Ocean. Now it was time to prepare her for the Pacific.

The decision to abandon the Barracuda had implications: The fleet would now be operating three different types of American aircraft, and two British types. This involved completely different sets of tools, spares and equipment.

Unicorn sailed for Durban in November for the necessary modifications, stores and personnel needed to meet this challenge.

Upon her departure in January, Unicorn visited India and Ceylon to gather up all available reserve aircraft and spares. She sailed for Sydney with 82 aircraft and 120 engines on board. There was room for more – had it been available.

Aboard the aircraft carrier HMS "ILLUSTRIOUS"... HMS INDOMITABLE taken from "Admiral's Platform" on HMS ILLUSTRIOUS. Cruiser HMS Newcastle in the background. Fleet is on way back to Trincomalee Ceylon. SEAC photo unit (US). Photographer: PFC Russell Scott. December 16 thru 23, 1944.

OPERATION ROBSON

“Then the fleet was off again, this time with our new gung-ho Admiral (Vian), cracking the whip and raring to go, for an attack on Pankalan Brandan where there was an oil refinery to be knocked out and two airfields to be strafed.”

Shot made on HMS INDOMITABLE by Lt Bennett: Left to right: Capt I.A.S. Eccles, Admiral Vian, and J.P. Wright, Commander, Admirals Chief of Staff, looking at chart in captain's cabin. SEAC Photo Unit (US).

Admirals Fraser and Vian were keen to put their new force to the job. They were also eager to demonstrate its powess - and to justify their own positions.

But Admiral Fraser was already in the Pacific, struggling to prepare the way for his fleet in Australia and to overcome the continued reticence displayed by many levels of USN command. Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Power, the new head of the Eastern Fleet, would stand in in his stead.

At sea, Rear Admiral Vian would be in command. Vice Admiral Rawlings had fallen ill upon his arrival in Ceylon and was unable to join the fleet.

A target was selected: Pangkalan Brandan. This was the northernmost of Sumatra's oil refineries.

Task Force 67 set sail on December 17, 1944.

HMS Indomitable was operating 50 aircraft:*

1839 Squadron, 15 Hellcat I

1844 Squadron, 14 Hellcat I

857 Squadron, 21 Avengers

HMS Illustrious carried 53 aircraft:

1830 Squadron, 16 Corsair II

1833 Squadron, 16 Corsair II

854 Squadron, 21 Avengers

Task Force 67 comprised the following warships:

Cruisers: Newcastle, Argonaut, Black Prince

Destroyers: Kempenfelt, Whirlwind, Whelp, Wrangler, Wessex, Wakeful

* All figures quoted are from David Hobbs' The British Pacific Fleet, unless otherwise attributed.

The tanker RFA Wave King, escorted by HMS Wager, shadowed the task force to replenish fuel stocks.

At dawn on December 20, weather over the target was very poor. Regardless, Admiral Vian insisted the two carriers launched a strike force of 27 Avengers covered by 28 Hellcat and Corsair fighters.

John Winton's Forgotten Fleet breaks the force down as:

Strike Force:

12 Avengers (Indomitable), four 500lb bombs each

16 Avengers (Illustrious), four 500lb bombs each

4 Corsairs (Illustrious), two 500lb bombs and a long-range tank each

Escort

Top Cover: 18 Hellcats (Indomitable)

Middle Cover: 12 Corsairs (Illustrious)

Close Cover: 8 Hellcats (Indomitable)

One of Indomitable's Avengers crashed shortly after take-off. Its crew was recovered.

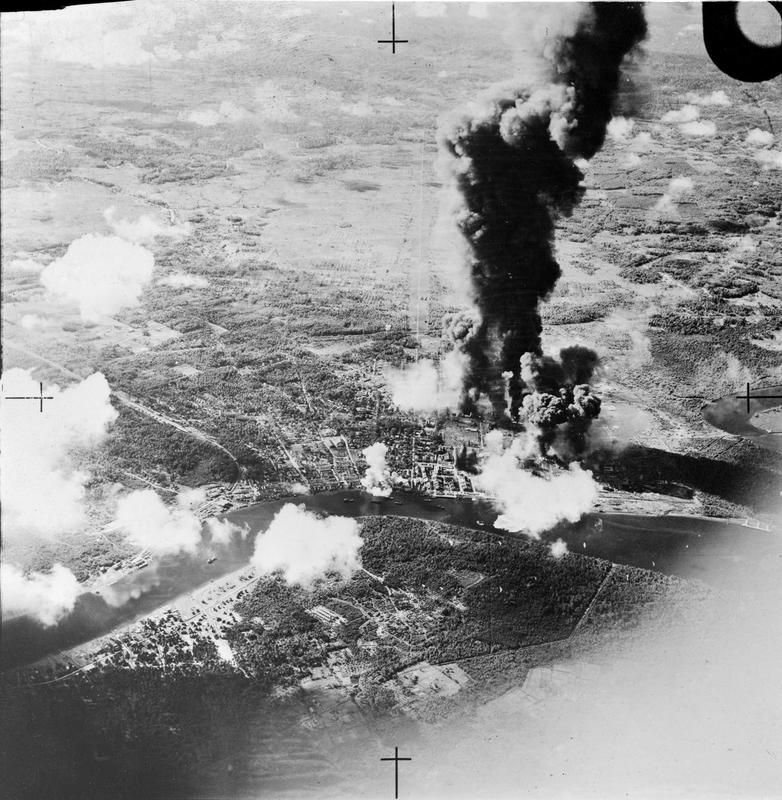

The remainder of the strike failed to find the primary target among the dense cloud and rain. So - amid general radio bedlam - the strike group's commander managed to order some of his aircraft to the secondary objective, the port of Belawan Deli, near the district center of Medan.

L. to R: Captain Charles Lambe, CB, CVO, and Commander Arthur Wallis on ships bridge (HMS ILLUSTRIOUS). Picture: SEAC Photo Unit (US).

The bomb-armed Corsairs were unable to locate their targets and returned to Illustrious.

The weather over the secondary target was little better: squalls and low cloud.

Aircraft dove for oil tanks, warehouses and railway facilities, lining up targets based on the barest of glimpses. Results were highly uncertain.

As the strike force withdrew, fighters strafed airfields near Sabang. Several aircraft were claimed as destroyed on the ground.

Top Cover Hellcats reported surprising a Sally bomber and shooting it down.

All aircraft returned to their carriers by 10.50.

Task Force 67 returned to Ceylon on December 22.

“As I started to fall into a sleep, befuddled with whisky fumes, I spared a thought for our Admiral (Vian) and how we aircrews must all try to do better for him, if he was to get his ‘K’ or whatever it was he so badly wanted.”

Men folding the wings of a Fairey Firefly of 1770 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm on board HMS INDEFATIGABLE on the aircraft's return from the carrier-borne air strike on the Japanese oil refinery at Pangkalan Brandan, Sumatra. Weather conditions were excellent and the whole weight of bombs and missiles from the Grumman Avengers and Fairey Fireflies fell within the target area. The powerhouse and other important plants, together with oil tanks and buildings, received direct hits.

OPERATION LENTIL

“Pangkalan Brandan was little talked about by the crews who attacked and we Seafires were on fleet patrol duty only. A solitary Dinah flew over the fleet at a great height and dropped a stick of bombs which missed us by several hundred feet... This was to be the Fleet Air Arm’s greatest operation of the war as far as damage to the enemy was concerned, although Palembang has never had the same recognition as Taranto, but whereas the attack on Taranto destroyed battleships which were not likely to put to sea anyway, Palembang destroyed huge oil refineries and oil wells which cut off the main Japanese supplies for the rest of the war.”

HMS Victorious was once again available. So was the freshly arrived HMS Indefatigable. With Indomitable (Vian's flagship), the three carriers would form the core of Task Force 65.

Indomitable deployed with a 50-strong air group very similar to that during Robson:

1839 Squadron, 15 Hellcat I

1844 Squadron, 14 Hellcat I

857 Squadron, 21 Avenger II

Victorious had tweaked her mix somewhat to 55 machines:

1834 Squadron, 18 Corsairs

1836 Squadron, 16 Corsairs

849 Squadron, 21 Avengers.

Indefatigable would operate Seafires and Fireflies along with her Avengers in her 73-strong air group. With hangars only 14ft high, she could not carry the Corsair. And not enough Hellcats had been trickling in from the US to sustain more than the handful of operational FAA squadrons already in existence.

887 Squadron, 22 Seafire FIII (Some accounts say only 16 went on the mission)

894 Squadron, 18 Seafire LIII (Some accounts say only 16 went on the mission)

1770 Squadron, 12 Firefly I

820 Squadron, 21 Avenger I

888 Squadron, 6 Hellcat F6F-3P PR (temporary deployment for Operation Lentil)

Task Force 65 would be escorted by:

Cruisers: HMS Argonaut, Black Prince and Ceylon. The Eastern Fleet heavy cruiser Suffolk was loaned by Vice Admiral Power.

Destroyers: Eight destroyers of the 25th and 27th Flotillas.

Major Cheeseman, Indefatigable's 1770 Firefly Squadron's commander:

Towards the end of 1944 the British Pacific Fleet forgathered at Ceylon and we immediately commenced intensive training in operating all these ships and aircraft as one compact unit. This, I might say, is no mean feat in itself since considerable skill is required in manoeuvring four or five carriers, together with their attendant support ships, at 30 knots and having to turn the whole force into the wind every time an aircraft wishes to land.

Apart from this, when flying off so many aircraft from so many ships the sky is very soon full of planes flying in all directions. An extremely high degree of airmanship and squadron drill is required and we had only had a limited time in which to attain the perfection required before we were to make our presence felt on the Japanese.

Within 10 days we were ready and the moment I had been so long awaiting had arrived. We were ready to strike and destroy the Japanese refineries at Pangkalan Brandan and Palembang in the Dutch East Indies island of Sumatra (now Indonesia). These enormous refineries were producing and supplying the Japanese with all their liquid fuel requirements for their armed forces in this theatre. To destroy them would paralyze enemy movements over their entire field of operations, and in particular ground all their aircraft. What a target! And what widespread effects it could have.

The task force departed Trincomalee on January 1, 1945. It arrived at its launch position near Simalur Island, north-west of Sumatra, three days later.

The launch area was kept outside the Malacca Straits as it was believed they were too well defended. However, Task Force 65's aircraft would now have to fly 130 nautical miles over Sumatra and climb over an 11,000ft high mountain range to reach their target at Pangkalan Soe Soe.

John Winton lists LENTIL's strike force as:

Strike:

16 Avengers (Indomitable), four 500lb bombs each

16 Avengers (Victorious), four 500lb bombs each

12 Fireflies (Indefatigable), eight 60lb rockets each

Escort:

Top Cover: 8 Hellcats (Indomitable)

Middle Cover: 16 Corsairs (Victorious)

Close Cover: 8 Hellcats (Indomitable)

RAMRODS:

8 Hellcats (Indomitable)

8 Corsairs (Victorious)

“The Jap’s cockpit seemed to glow as I hit him with a long burst, and I could see the bullets striking the engine and cockpit. He levelled out at 300 ft and then went into a climbing right hand turn. I fired again and the pilot baled out as the aircraft rolled over and went into the sea. I watched the pilot land in the water, but he appeared to be dead.”

The RAMROD (fighter strike) of 16 Corsairs and Hellcats was launched shortly after dawn (06.10) on January 4. Their job was to suppress the airfields at Bindjai, Medan, Tandjonpoera and Troemon - all within the approach path to the target. A Ki46 'Dinah' and Ki21 'Sally' were bounced as they attempted to land, and several more were claimed destroyed on the ground. In all some 25 aircraft were reported sighted on the ground at Medan and Tanjong Pocra airfields. Seven were claimed destroyed.

Indefatigable's 1770 Squadron's 12 Fireflies were to precede the main strike. They were to unleash their rockets and 20mm cannon in an effort to suppress defences at Pangkalan Soe Soe. Arriving at target at 08.25, they found no Japanese aircraft or anti-aircraft guns active. Some rockets went astray and ignited fuel tanks, obscuring the target partially for the follow-up Avengers.

Close behind were two waves of 16 Avengers, each lugging four 500lb bombs. These were from Victorious and Illustrious.

Indefatigable's Avengers had not had the same degree of 'working up' as her colleagues, so they were reserved for anti-submarine patrols during this operation. Likewise, her Seafire's did not have the range to reach the target. To them fell the duty of CAP defence of the fleet.

Henry "Hank"Adlam: On and Off the Flight Deck: Reflections of a Naval Fighter Pilot in World War II

Most of our Hellcats would act as top and close escorts to the Avengers and Fireflies, about seventy aircraft in all, but I felt fortunate to be one of the eight to carry out an advance Ramrod on the Japanese fighter airfields at Medan and Tanjong ... It was a pleasant change to form up after take-off with only seven other aircraft and then our flight of eight Hellcats took position at a reasonable open distance behind and below the Corsairs. There was a distance of about 120 miles to the first target at Medan. The arrangement was that, once at the target, the Corsairs would remain at top cover to deal with any Japanese fighters already airborne while we Hellcats, at ground level, would set about strafing aircraft and whatever other targets were on the airfield. As soon as we had passed over the mountain range, flying at 12,000 ft, we separated from the Corsairs and put our noses down to pick up speed, intending to arrive at the target airfield going fast and low. I was leading the flight on the left and approaching the enemy airfield now coming into sight, I put us into a wide echelon port as previously briefed. The other flight on my starboard side led by Noel, the Senior Pilot, were also in similar wide formation. We were flying very low and wide enough to pick our individual targets as we came on to the airfield. And what a mass of fighter aircraft, grouped on either side of the runways, was laid out for us as targets. We had caught those horrible little bandy-legged barbaric Japs with their pants down. I had only to jink slightly to the right to line my sights up on the first of four enemy fighters (Oscars) which, with a number of Japanese around them, were probably preparing to start engines ready to taxi out for take-off on patrol. I could see the pilots in their cockpits as I flew low and fast towards them. I had done this sort of thing quite a few times by now, but the intense and lethal firepower produced by my six Browning 0.5 machine guns could still shock me. At that speed there was not much more than seconds in which to fire and hit the targets. But it was enough. The first Oscar disintegrated then burst into flame as I flew over and past it and I had seen the bullets hitting the cockpit, with the pilot inside, and the men near the aircraft. So quick and apparently silent had been our attack that only then did the gun emplacements of the enemy come alive and begin to fire at us. The Hellcats on either side of me had found targets too, and keeping very low and fast, we flew on past and clear of the far end of the airfield ... Nothing else seemed to be going on so Hellcats and Corsairs returned to land on their respective Carriers where I found a fairly large hole, probably from a cannon shell, in the rear of my Hellcat's fuselage.

“Evidently these Japanese fighters had taken off from Tanjong airfield before our flights had arrived there making it obvious, in retrospect, that the Corsairs acting as our top cover would have been better employed in flying direct to Tanjong. But aircrews of the Avengers complained bitterly that their escorting Hellcats and Corsairs had deserted them to have dog-fights with the Japs.”

At 08.31 the Avengers of 867 Squadron hit the main Pangkalan Brandan refinery. 849 Squadron hit the Edeleanu Plant at 08.33.

By now Japanese defences were alerted. A group of fighters fell on the Avengers.

One Avenger was hit and damaged. But soon the high cover Hellcats and Corsairs were among them, shooting down seven enemy aircraft. It was a successful defense - despite 15 of the high cover force having earlier broken formation to strafe ground targets.

“‘Whizzing about over Pangkalan Brandan, I felt a creepy feeling underneath and rolled over. Beneath me was an “Oscar” on the same course. I could see the pilot’s hands, knees and feet. I immediately rolled and climbed madly without him seeing me. The rest was a no contest, as his aircraft caught fire immediately I attacked. The “Oscar” was fragile, and certainly not well flown – I felt guilty.’”

The return of the strike force over the mountains proved to be a harrowing affair. 1770 Firefly Squadron's commander, Major Cheesman, ran out of fuel on the landing circuit and had to ditch his aircraft. He had been in the air 4 hours and 35 minutes - only to be held up by a Seafire prang on his home deck. Subsequent examination of the Fireflies revealed the machines to have wildly different fuel consumption rates, largely due to inexperience in tuning the engines for the tropics.

It had not been an ideal time for Indefatigable's Seafires, either. Several had crashed during their CAP operations.

Later in the day, 888 Squadron's PR Hellcats returned. Their photographs, quickly processed and distributed, revealed the strike to have been accurate and the strafing attacks on the airfields as effective. The central pumping house, power plant, trumble plant and pre-topping plant had been wrecked. Eight pre-topping tanks and five oil storage tanks had been set on fire.

It was later learnt that the Pangkalan Brandan refinery had had its long-term output reduced by at least one third.

The Fireflies had also damaged a small tanker, setting it alight. The RAMROD fighters were credited with destroying seven aircraft on the ground (as well as the two in the landing patterns). Five more were assessed as damaged.

All aircraft were landed-on by 10.33. Task Force 65 turned for home at 12.30, refueling from Wave King on the way.

The fleet arrived back at Trincomalee on January 7. Waiting for them were orders to proceed to Sydney, Australia. But there was to be a significant stop-over on the way: Operations Meridian I & II.

“The post-mortem on the second strike against the Pankalan oil refinery concluded that it had been a success, having put the whole refinery out of operation. But our Admiral Vian was scathing about the lack of discipline in the air by our aircrews. During the coming weeks, we aircrews would discover that he tended to be scathing about many of our efforts and we could only presume that it was his method of keeping us up to scratch. But it was a poor form of leadership. His method would have been better received had he showed himself more interested in obtaining an understanding of the factors involved in flying from Carriers. It would have been appreciated if, for example, he had flown in the back of a Firefly or Avenger during any one of the major Wing exercises, just to see what it was like.”